Kofun – The mystery of japan’s ancient burial mounds

Kofun are one of the best things about living in Japan―especially when you live in Kansai and you’re surrounded by them. Southern Nara and Eastern Ōsaka in particular are riddled with kofun to the point you feel like Indiana Jones just walking down the street. Some have been turned into parks, some museums and others have been reconstructed to appear the way archaeologists believed them to have looked when they were originally constructed. With over 160,000 kofun scattered around the country in addition to the thousands more that have yet to be discovered, it’s impossible to visit them all.

Personally, I’ve visited around 30 kofun believed to belong to important figures from Japanese history, including the tombs of the first ten emperors. Every morning when I open my curtains, I’m greeted with the view of a 650ft long kofun, which I take a stroll around every day. But what are kofun and why are they so many of them? The amount of information known about them is enough to fill dozens of books, but I’m going to keep it very basic and hopefully teach you enough to encourage you to explore some of the more famous kofun should you ever decide to come to Japan.

Naming

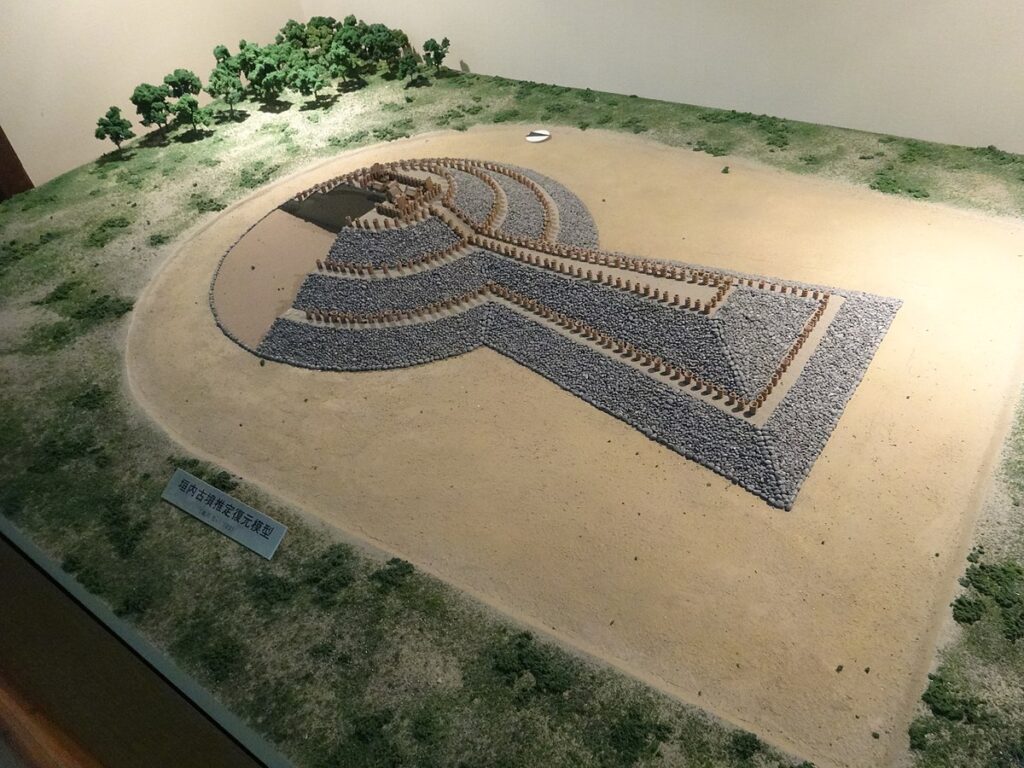

The word ‘kofun’ consists of the Chinese characters 古(ko) and 墳(fun), which mean ‘old’ and ‘tomb’ respectively. It’s as simple as that! There’s no difficult terminology when it comes to kofun as there is no written history regarding them. Since no one knows what they were called at the time they were constructed, archaeologists are free to come up with any names for the various types of kofun that they wish. And so they keep the names deliberately simple. To be precise, the name of each type of kofun is basically a description of its shape. For example, the most famous type of kofun, zenpōkōenfun(前方後円墳), simply means ‘front square, back round tomb’. In English, however, it’s described as being keyhole-shaped. Zenpōkōenfun is an apt name that not only describes the shape of the tomb but also the direction it faces. So while there is a lot to remember about kofun, thankfully there are very few difficult words you need to know to enjoy the topic.

Origin

Basic small circular and square kofun were built during the Yayoi era, but it wasn’t until the Kofun era that they grew in size, became more complex in form and began to spread around the country. This new design of kofun was employed from roughly the years 280-645. Since no written history exists for most of that period, historians can only surmise the reasons for their construction. Their best guess incorporates information gleaned from the Gishi-wajinden, a Chinese text documenting reports from Chinese envoys sent to Japan in the Yayoi period. This text teaches us that a war broke out in Japan around the end of the 3rd century, with numerous tribes vying for control of the country.

The war presumably left many dead, meaning there were fewer people to tend the rice fields. In addition, during the extended period of conflict, many of those fields would have dried up. As famine spread around the country, people would have put down their weapons and banded together to create new fields, digging out large mounds of earth in the process. With no other use for these mounds, they were shaped into hills and used as lookout posts. Over time, these hills would have come to represent an area’s rice yield: large mounds = large areas of earth were dug up = numerous rice fields. As the centrepiece of the area, the richest and most influential person would naturally have selected it as their burial place. From there, the trend presumably picked up and important figures began to compete for the largest and most complex burial mound, giving rise to the sensation now known as kofun.

Size, shape and form

Kofun range in size from 14,000-74,000,000 cubic feet. They come in a variety of shapes, including round, square, octagonal, clam-shaped, the aforementioned keyhole-shaped and a variation on the keyhole-shaped kofun that uses two squares instead of a square and circle. They were constructed by accumulating piles of earth and solidifying them with clay and sand. Near the centre of the kofun, a burial chamber was dug out. These could either be in the form of a pit or a cave. In the case of a cave-shaped burial mound, the chamber can often be reached via a long tunnel, which is sealed off to prevent entry.

Once constructed, a number of rituals were presumably carried out on top of the kofun, after which the entire area would have been sealed off. The kofun would then remain untouched, the seeds buried in the earth used for its construction eventually growing into trees that took over and transformed the external structure into an extension of the land surrounding it. This is what makes it so hard to find kofun; viewed from ground level, they just look like small hills! In fact, during the Muromachi and Azuchi-Momoyama eras, daimyō often used kofun as bases to build castles on without even knowing what they were!

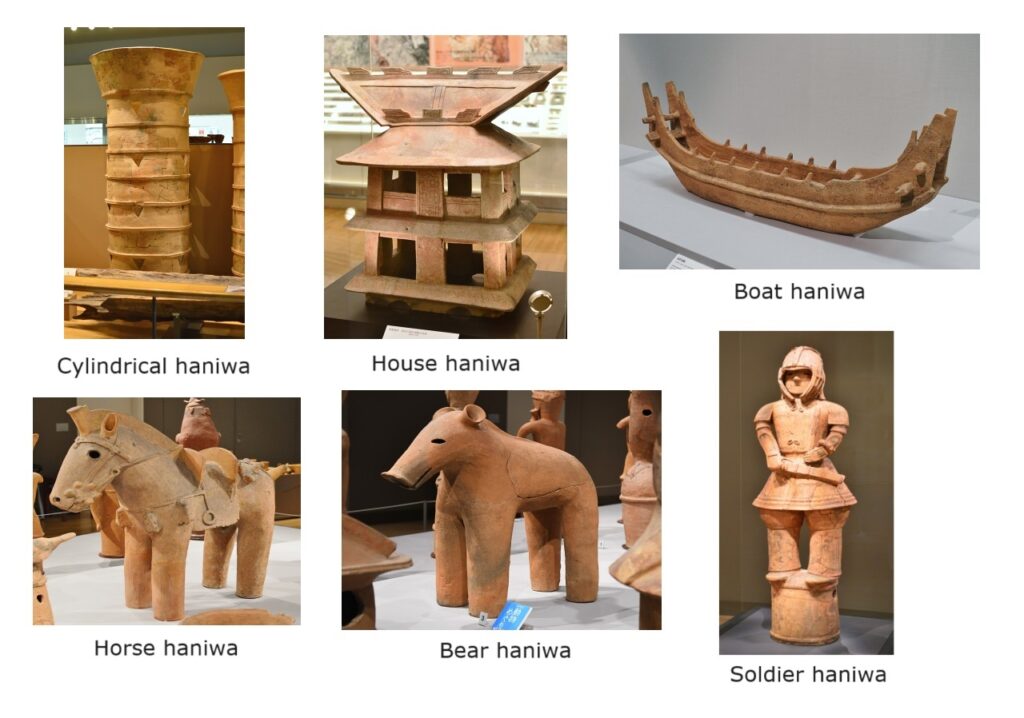

Haniwa

You can’t discuss kofun without touching on the subject of haniwa. These terra cotta clay figures are believed to have been lined up along the contours of kofun for use in rituals and to drive away spirits. Basic cylindrical haniwa first appeared in the 3rd century and evolved over time to encompass a variety of shapes. By the 4th century, haniwa in the forms of animals, houses and tools made an appearance. In the 5th century, people-shaped haniwa finally emerged. These haniwa give us small but vital clues as to the clothing, hairstyles, armour and architecture of a time with no documented history.

The Nihonshoki states that Emperor Suinin―the 11th emperor of Japan―created haniwa as an alternative to human sacrifice. Prior to his reign, before a kofun was sealed off, a number of people and animals would be locked inside as offerings to the deceased. Feeling this ritual to be barbaric, Emperor Suinin decided to use clay figures of animals and people instead. However, archaeological discoveries regarding datings of the earliest haniwa and the emergence of different forms of haniwa contradict this explanation.

The Largest kofun

The largest kofun in Japan is Daisenryō Kofun in Sakai City, Ōsaka. While the mound itself is an incredible 1,722ft long, the entire complex including the surrounding pond measures in at a whopping 2,782ft, making it not only the largest tomb in Japan but one of the three largest tombs in the world along with the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor in China and the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt. Constructed in the 5th century, it is believed to belong to Emperor Nintoku, the 16th emperor of Japan. The site was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019.

The Oldest kofun

While it’s almost impossible to even define what the first kofun was in Japan let alone go about searching for it, historians are fairly sure they’ve managed to pinpoint the location of the first zenpōkōenfun. Uramachausuyama Kofun(it’s a mouthful) in Okayama prefecture dates back to the late 3rd century and measures 453ft in length. Its treasures were robbed when it was broken into during the late 19th century, but an excavation carried out in 1988 unearthed some fragments of mirrors, copper arrowheads, an iron sword and a number of farming and fishing tools. This kofun also contains the earliest examples of pottery that would later become the basis for haniwa.

Hashihaka kofun

While Uramachausuyama may be the oldest zenpōkōenfun, Hashihaka Kofun in Nara prefecture is perhaps more significant. Constructed around the same time, it is twice the size and exactly the same shape. The fact that Hashihaka contains pottery brought over from Okayama suggests that the two kofun have a strong connection. Hashihaka would go on to become the standard for the 4,700 or so zenpōkōenfun that were constructed later. This fact combined with the knowledge that construction of zenpōkōenfun was only permitted for members of the Yamato court and its allies suggests that Kibi, a large and powerful society believed to have existed in Okayama during the kofun period, either played a large part in the formation of the Yamato court, or its members moved east and actually established the court. As the Yamato court was ruled by the same imperial line that rules Japan today, both Uramachausuyama Kofun and Hashihaka Kofun could hold major pieces of the puzzle regarding the origin of the Japanese Imperial Family.

The kofun itself is believed to belong to Yamatototohimomosohime no mikoto(another mouthful)―daughter of Emperor Kōrei, the 7th emperor of Japan. However, another theory suggests that the tomb belongs to Himiko, ruler of Yamataikoku, which is theorised to be the origin of the Yamato court. If this were true, it would, again, explain a lot about the origin of Japanese society. Unfortunately, though, since the kofun was constructed 30 years after the death of Himiko at the earliest, not all historians support this theory.

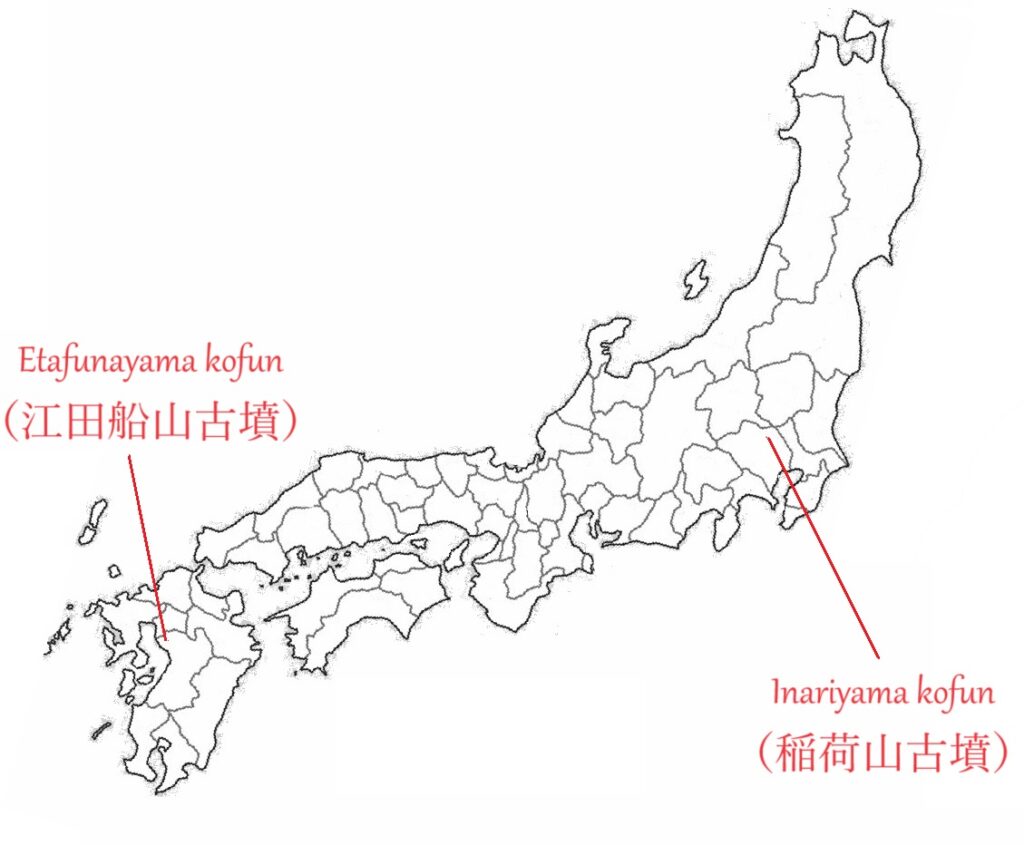

The Wakatakeru swords

Now that I’ve covered the basics of what kofun are, let me give you an example from recent history that highlights their significance. In 1968, archaeologists discovered a 29-inch-long iron sword in Inariyama Kofun, Saitama prefecture. Naturally, the sword was rusted and covered in dirt, but it was still in good enough condition for an X-ray evaluation to reveal 115 Chinese characters inscribed along the length of its blade. Among these characters was the word ‘Wakatakeru’. Several more characters suggested this to be the name of the king who awarded the sword to the kofun’s occupant. Historians aren’t sure about the identity of Wakatakeru, but given that they more or less know the year the sword was forged, their best estimate is the 21st emperor of Japan, Emperor Yūryaku.

While this alone would constitute a fairly impressive discovery, what’s even more impressive is the fact that the sword helped historians solve the mystery of another sword that had been discovered almost 100 years prior. Excavated in Etafunayama Kofun, Kumamoto prefecture, in 1873, this sword had not been stored in good enough condition to allow its inscription to be read. As only a handful of the characters could be made out, historians could only guess as to the name inscribed on it. However, with the discovery of the Inariyama sword, they were finally able to figure out that it too was a ‘Wakatakeru’ sword. The upshot of this revelation is that whoever Wakatakeru was, at the very least, he ruled the area of Japan between Kumamoto and Saitama. This allows us to know with some degree of accuracy the power of the Yamato court in the 5th century.

Rewriting the past

The Wakatakeru case is a prime example of the kind of knowledge that is buried away inside of kofun. In 2023, a sword and shield unearthed in Nara unlike any other found up until that point suggests the existence of an unknown clan―a possible rival of the Yamato court. With further excavations planned in the coming years, who knows how history will be rewritten in the near future. Unfortunately, excavation of any kofun assumed to belong to former emperors or members of the Imperial Family has been banned by the Imperial Household Agency(presumably due to the fact we’d likely discover that most of them don’t actually belong to anyone related to the emperor, and they may even contain proof that the current emperor isn’t a blood relative of the original rulers of Japan). If archaeologists were to be granted access, the amount of information we’d be able to obtain about the kofun period, the 150-year gap in Japanese history where the country disappeared from Chinese texts and possibly even the location of Yamataikoku is unfathomable. Here’s hoping one day the Imperial Household Agency finally grants us that permission.