Shōtoku Taishi – Was he real?

Every now and again history throws out a character so accomplished and yet so shrouded in mystery that they beg the question ‘Were they real?’. Of all such people, there are perhaps none so famous as Shōtoku Taishi. His face has adorned seven varieties of Japanese banknotes over the past hundred years―a feat unrivalled by any other historical figure.

In the Heian era, he was worshipped as a Buddhist master. To the samurai of Sengoku, he was a god of war. The Meiji government revered him as a captain of diplomacy, and since World War 2 he has been exalted as a symbol of peace. Is it possible though that throughout the ages, Shōtoku Taishi has been nothing more than a blank canvas onto which people project the major theme of the times? Or is he really as accomplished as history would have us believe? Let’s dive into the life of this mythical(real) legend and study the arguments for and against his existence.

Shōtoku Taishi’s real name

Before we can even begin to go over the life of Shōtoku Taishi, we first need to sort out the problem of his name. Since the name ‘Shōtoku Taishi’ first appeared 129 years after his death, it’s highly unlikely he was ever actually referred to by it while he was alive. ‘Shōtoku'(聖徳) loosely translates to ‘heavenly virtue’ while ‘Taishi'(太子) means ‘crown prince’. While he was admired for his virtuous deeds regarding the spreading of Buddhism, and while he was in fact a prince, it’s more likely that this name was awarded to him either as a posthumous Buddhist name or an affectionate nickname. Whatever the case, it is the name by which he is most widely known today, and it is the name by which I will be referring to him throughout this article.

His real name appears in several forms across many texts―again, all of which were written a number of decades after his death. These texts all include some variation of the names ‘Umayado’ and ‘Toyotomimi’. The most likely theory is that during the time he was alive, Shōtoku Taishi was known as Prince Umayado no Toyotomimi. ‘Umayado'(厩戸) means ‘stable door’. This refers to the fact that his mother gave birth to him by a stable door. ‘Toyotomimi'(豊聡耳) is either a coined term or an ancient Japanese word used to describe someone with impeccable hearing. The name most likely refers to a famous anecdote regarding the prince in which he listened to ten people talking at the same time and was able to understand and respond to each of their queries with no struggle whatsoever.

‘Stable door good ears’ brings into question the naming sense of people at the time, but when you consider some of the names that make an appearance in the Kojiki and the fact that nowadays some people name their children after cars and fashion brands, it’s not really all that bizarre.

Early life

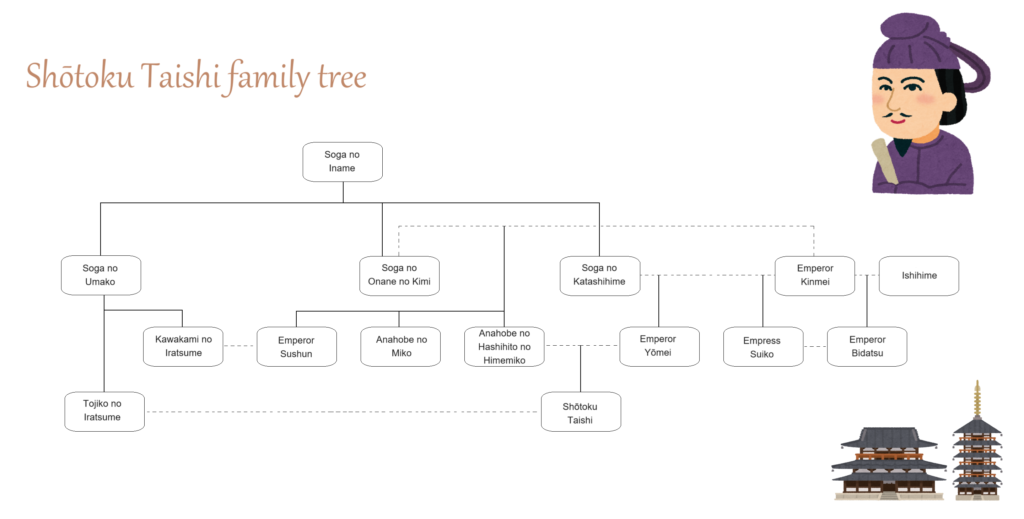

Shōtoku Taishi was born in 574. His mother and father were half brother and sister, their father being Emperor Kinmei and their mothers both daughters of Soga no Umako. This gave the young prince extremely strong ties to both the Imperial Family and the Soga clan―the two greatest powers of the time.

His father ascended the throne as Emperor Yōmei in 585 after the death of his brother, Emperor Bidatsu. However, Emperor Yōmei died of smallpox just two years later. As his successor had not yet been decided, an opportunity arose for his two highest-ranking officials, Soga no Umako and Mononobe no Moriya, to select and support a candidate whom they could turn into their puppet.

Moriya had long supported Prince Anahobe, and Umako already had his sights on Prince Hatsusebe, both sons of Emperor Kinmei(how many kids does this guy have??). Anahobe went a bit crazy from his desperation to become emperor, though, and ended up unsuccessfully trying to sexually assault Emperor Bidatsu’s empress(also, incidentally, a daughter of Kinmei). Furthermore, Moriya had started to go off him ever since he brought a Buddhist priest to the capital to pray for Emperor Yōmei after the emperor fell sick. (The Mononobe’s religious stance had always been the abolition of Buddhism and the support of Shintō.) In short, Anahobe lost his backing. The former empress issued a decree to Umako ordering him to kill Anahobe. Umako, in an ‘enemy’s enemy is your friend’ kind of way, teamed up with Moriya to get the job done.

The end of the Mononobe

Once their mutual enemy was out of the picture, Umako and Moriya naturally resumed their rivalry. Umako and prepubescent Shōtoku Taishi gathered an army and marched to Kawachi in the east of Ōsaka, where Moriya’s estate was located. Once they arrived, they began the assault. It didn’t go as easily as they’d planned though; the Mononobe had been at the centre of the military for over 50 years. Moriya had his army build a wall out of straw to hold off Umako’s soldiers, and succeeded in repelling three waves of attacks while he hid himself in a tall tree and fired arrows down at the advancing army.

Amidst the chaos, Shōtoku Taishi removed himself from the battlefield and cut down a small tree, widdling its bark into the shape of the Four Heavenly Kings of Buddhism. He prayed to the small statues, vowing that if they helped him defeat Moriya, he’d build a temple in their honour and devote his life to spreading Buddhism to all corners of the country. Before long, one of Umako’s soldiers struck Moriya down. Its leader defeated, the Mononobe army fled. The battle was done, and the Mononobe family faded out of history.

After returning to the capital, Umako had Prince Hatsusebe ascend the throne as Emperor Sushun. He continued to control the court from behind the scenes until his puppet got frustrated and started to make a bid to take back the court’s power in 592, at which point Umako had him assassinated. A year later, he had Empress Bidatsu’s empress take the throne as Empress Suiko. With the political situation in the capital finally stabilised, Suiko, Umako and Shōtoku Taishi ruled together for the following 30-plus years.

Political achievements

As per his vow, Shōtoku Taishi built a temple dedicated to the Four Heavenly Kings―Shitennnōji. In 601, he began construction of a palace in Ikaruga, situated halfway between the capital and his recently-constructed temple. There he erected the infamous Hōryūji, one of Japan’s oldest temples and the oldest wooden structure in the world. Some claim he moved to Ikaruga to escape Soga no Umako and establish a new power base, but so far no records or archaeological discoveries have been able to back this claim up.

The Twelve Level Cap and Rank System

One of the prince’s most famous achievements was the creation of the Twelve Level Cap and Rank System. Until its establishment, ranks and positions within the court were granted to families and passed down from generation to generation. However, there were no individual ranks to signify the status of each person within a family. Considering the fact that Sui already had such a system in place, Shōtoku Taishi decided that Japan should adopt a similar system. That way, when sending envoys to or greeting envoys from Sui, both sides could determine the precise authority of the people they were dealing with.

Shōtoku Taishi named the ranks after the five constant virtues of Confucianism and the term ‘virtue’ itself. Each of the virtues had an upper and lower version, and each had its own colour of clothing to represent it. Those awarded the upper version of a particular rank were allowed to wear a darker shade of clothing while those awarded the lower version wore a lighter shade. The ranks and their associated colours in order from highest to lowest were as follows:

徳 virtue (purple)

仁 benevolence (blue)

礼 gratitude (red)

信 sincerity (yellow)

義 morality (white)

智 wisdom (black)

The Seventeen-Article Constitution

Shōtoku Taishi is also credited with having written Japan’s first constitution: the Seventeen-Article Constitution. Granted it was more of a social etiquette guide than a set of rules by which a country should live and die, but for a fledgling court looking to better manage its people, it was a great accomplishment.

The first few articles were basic common sense for the time: Believe in Buddhism, respect the emperor, and so on… Others explained how subordinates should follow the rules set out by their leaders, and how leaders should rule fairly and justly. Punish the bad, reward the good… Perform your duties correctly… Big decisions should be made by a council, but small decisions can be made by individuals… Basic common sense for our time, but for the people of the Asuka era, these articles were revolutionary.

Diplomatic Envoy

The young prince is also famous for having sent envoys to Sui. Although he wasn’t the first to have done this, the envoy he sent in 607 led by Ono no Imoko is famous among Japanese people even today. The correspondence he sent to the Chinese emperor contained an expression that more or less translates to ‘From the emperor of the land of the rising sun to the emperor of the land of the setting sun.’ This infuriated Sui’s emperor for two reasons: The first is obvious―the metaphorical image of the sun setting on his country taken to mean that Sui was on the decline and the Yamato court was on the rise. (It turned out to be true, incidentally. The Sui dynasty ended just 11 years later!) The second reason was the use of the word ’emperor’. As far as Sui’s emperor was concerned, he was the one and only emperor in the world.

Fortunately for the Yamato court, Sui was in no position to take action; they happened to be at war with Goguryeo at the time and desperately needed to keep Japan as an ally. Most likely, Shōtoku Taishi was aware of this fact, and so he took a calculated risk in order to let the emperor know that while the court had no intention of becoming a part of the Sui empire, it was more than happy to maintain good relations with it.

For the following ten or so years, Shōtoku Taishi devoted himself to writing Buddhist texts and working towards the expansion of his temples. He died in 622 at the age of 48, just one day after the death of one of his four wives. Due to the timing of their deaths, a number of historians believe that he and his wife were poisoned. Several theories exist regarding the identity of the assassin, but there is too little evidence to perhaps ever definitively prove any one of them.

Was he real?

I should preface this section with a small disclaimer: most of the evidence surrounding the theory that Shōtoku Taishi wasn’t real is circumstantial. For example, the fact that all texts that make mention of him were written a considerable length of time after he died, the fact that there are no mentions of him at all in Chinese history books, and the fact that there is no evidence that he wrote any of the Buddhist texts he was claimed to have written. On the other hand, the same could be said for most people from Shōtoku Taishi’s era. So why target Shōtoku Taishi specifically?

The legends surrounding him don’t do him any favours; they only serve to put a target on his back. Is it really possible to be able to listen to ten people talking at the same time and respond to every one of them? In actual fact, every text that references this story quotes a different number, with one of the more recent texts exaggerating it as high as 36! But perhaps an alternate interpretation can provide some truth to the myth. Shortly before the prince was born, a large number of people immigrated to Japan from various countries. It’s entirely conceivable that a large minority of the population did not yet speak the local language. Is it possible that ‘listening to ten people at the same time’ really means being able to understand ten different languages? Perhaps the prince was highly educated and skilled in linguistics to the point he was able to act as an interpreter for every member of the community.

What about the fact he was born in a stable? Doesn’t that sound similar to another historical figure who spread the word of religion? It’s conceivable that among the many people who entered the country in the 5th and 6th centuries, at least one of them brought a copy of the bible. Did whoever wrote the Kojiki fabricate the story in an attempt to create a religious role model for Buddhism as successful as that of Christianity?

Other stories defy interpretation. One particular tale claims that the young prince had wealthy landowners from provinces all over the country send him horses. After examining each of the horses, he determined that one was a sacred animal. He kept it in his stables and had his servants care for it. Then one day, as he was riding the horse, it took off into the sky and flew far east, past Mount Fuji to the Kantō plain before returning two days later.

The birth of Shōtoku Taishi

But what infamous historical figure doesn’t have a few legendary stories? That’s part of the reason they become so famous in the first place, isn’t it? Surely mythology alone isn’t enough to claim they didn’t exist. Thankfully, there is a more academic theory that argues the case. In 1999, a historian named Ōyama Seiichi published a book titled ‘The birth of Shōtoku Taishi’. In it he outlines his theory, which states that when emperor Tenmu ordered the publication of the Kojiki and Nihonshoki, he had history rewritten so that achievements accomplished by more influential people within the court(most likely Soga no Umako) were attributed to Prince Umayado. This allowed the emperor to claim that all major political changes made during the Asuka era were brought about by his bloodline rather than that of any other family(the Soga).

The theory also contains some more concrete evidence, such as the fact that the Seventeen-Article Constitution contains words that were not yet in use during the time Shōtoku Taishi was alive. This suggests not only that Shōtoku Taishi was not responsible for the accolades detailed within these ancient texts but also that they were written many years later than claimed.

History is written by the victors. When you consider the fact that after the deaths of Shōtoku Taishi, Umako, and Suiko, the Soga family went on to rule the court for almost 20 years unchallenged, it’s unlikely that during his lifetime the prince’s authority exceeded that of Umako. A variation of Ōyama’s theory even goes so far as to claim that the real Shōtoku Taishi was a son of Umako born in the year 586. As little is known about this figure’s life or death, it’s not beyond the realms of possibility that he carried out all of Shōtoku Taishi’s accomplishments before being killed by the imperial line in during the Isshi incident and written out of history. Who was responsible for destroying the Soga family in the Isshi incident? Prince Naka no Ōe and Nakatomi no Kamatari. Who oversaw the production of the Kojiki and Nihonshoki? Prince Toneri and Fujiwara no Fuhito―nephew of Prince Naka no Ōe and son of Kamatari respectively.

Conclusion

So who was Shōtoku Taishi? Was he a devout Buddhist, a master diplomat, a talented statesman and a bringer of peace worthy of being literally worshipped?(he has his own religion!). Or was he a no-name prince who lived a life of luxury without contributing anything to society but, as fate would have it, was pulled out of the pit of obscurity to have the achievements of others thrust upon him for the sake of his descendants? We may never know. But whether his life as recorded in ancient texts is true or not, there’s no denying that it makes for interesting study. And after all, a little embellishment never did any harm… Okay, much harm…

Bonus fact

A book written in the Edo era claims that Shōtoku Taishi is responsible for the creation of the ninja. It states that he employed a man by the name of Ōtomo Hosohito to infiltrate his political rivals’ territories and discover their secrets. He referred to this role as ‘Shinobi'(志能便). The Chinese characters for this name presumably evolved into the one used today: ‘忍’, meaning a person who conceals themselves. Exciting as this is, unfortunately the story isn’t mentioned in any other historical texts from any period of time, making it highly unlikely that there is any truth to it. As the text was written more than 1,000 years after his death, however, it begs the question: ‘Is history done with Shōtoku Taishi?’. What new legends remain to be written about the mysterious prince in the years, decades and centuries to come?