Miyamoto Musashi – Was he real?

Japan loves a sword master. Of the many who made a name for themselves during the Muromachi era, the most influential has to be Kamīzumi Nobutsuna, founder of the Shinkage style, which went on to influence countless schools throughout the Edo era. One such school run by the Yagyū clan popularised the Yagyū Shinkage style, created by legendary sword master Yagyū Munemori, whose descendants went on to become the official instructors of the Tokugawa.

Despite their impressive resumes, though, neither Nobutsuna nor Munemori succeeded in becoming household names. In fact, only those with more than a rudimentary knowledge of Japanese history have any idea of who they were and what they contributed to Japanese sword fighting. Miyamoto Musashi, on the other hand, is one of the most famous figures in all history. His exploits became the subjects of kabuki plays and ukiyo-e paintings all through the Edo era, and as Japan progressed into the modern age, these stories and images were passed on to new forms of media, such as novels, comics and movies. To be precise, Musashi has been the subject of over 25 novels, 13 comics, 30 movies and 15 TV dramas!! But is he deserving of this worship? What exactly did he manage to contribute to the country that Nobutsuna and Munemori couldn’t? Were his exploits real, or did he simply have one of the greatest PR teams in history? Let’s dive into the life of this legendary warrior and see if we can separate fact from fiction to try to find the real Musashi.

Miyamoto Musashi as Recorded by History

So where do we start? There are numerous texts which detail events from Musashi’s life, but only one contains any information on his early life: Gorin no sho, the Book of Five Rings―a five-part anthology written by Musashi in his final years explaining his history, his philosophy and his sword techniques.

Musashi states in Gorin no sho that he embarked on his journey of sword mastery at the age of 13 and fought around 60 masters from the ages of 13 to 29, all of whom he defeated. Wow… An undefeated champion! No wonder he’s been so revered for over 400 years! The only problem is that of those 60-plus battles, only 18 were recorded in any other documents(and even then, most of their reports are dubious). So what can we assume of the other 42 or so? By comparing information, or even lack of information, from other sources, we can get some idea as to what Musashi was up to during his youth.

If the bouts alluded to in Gorin no sho were sanctioned by the provinces in which they were conducted, it’s likely that some form of documentation would have remained. If any of Musashi’s opponents belonged to a famous school, that school would have kept records of the fight(as was the case for Musashi’s vendetta against the Yoshioka, which we’ll look at later). The fact that so few such documents exist suggests that even if we were to assume that Musashi didn’t exaggerate the number, the majority of his opponents were most likely unskilled amateurs he happened to run into during his travels. We can also assume that a great deal of these fights were fought with wooden swords; a number of people who were in close contact with Musashi(and even Musashi himself) make mention of the fact that he favoured wooden swords over real swords.

The Modern Image of Miyamoto Musashi

Despite the lack of documentation regarding Musashi’s early years, people have a very specific image of his life: an image of young Musashi embarking on a journey of sword mastery with his on-again off-again girlfriend, Otsu, and his childhood friend, Matahachi. The three part ways and reunite multiple times throughout the course of Musashi’s life as he fends off a constant stream of contenders to his title of sword master and participates in famous battles of the time, including Sekigahara, the siege of Ōsaka and the Shimabara rebellion.

This image was created by renowned historical novelist Yoshikawa Eiji, who chronicled Musashi’s story in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper from 1935-1939. This account of Musashi’s life was later used as the basis for the bulk of the novels, comics and movies depicting his story, including 2003’s Taiga drama.

Between the newspaper serial, the Taiga drama and the recent manga ‘Vagabond’, most people today know Musashi’s story to some degree. Many, however, are unaware that both Otsu and Matahachi were fictional characters created by Yoshikawa to flesh out the story. Moreover, Yoshikawa based his interpretation of Musashi’s life off of a compendium of documents compiled by Kumamoto prefecture in 1909 which was claimed to be historically accurate. The information contained within the compendium was obtained mainly from a text written in 1776 known as the Nitenki. The Nitenki, in turn, was an updated version of a text written in 1755 known as the Bukōden, which contained a collection of stories regarding Musashi passed on to its author by the author’s father, who, in turn, had heard them from disciples of Musashi in his final years.

The Nitenki, however, contains certain details that are nowhere to be found in the Bukōden. For example, it introduces Musashi’s opponent from his battle at Ganryūjima as ‘Sasaki Kojirō’. Kojirō’s surname cannot be found in any earlier documents. This name was passed down to Yoshikawa, who spread it around the country via his serial novel and convinced the nation that it was fact. The text also details several manga-esque battles against a spear master, a sickle expert and students of the infamous Yagyū school of sword fighting, none of which can be found in any other source

In summary, the average Japanese person’s knowledge of Musashi comes from a novel based on a modern-day compendium of information based on a dramatised account of a document containing third-hand information passed down from Musashi at the end of his life. At this point, there are too many layers of exaggeration that need to be peeled off for us to ever know who the true Miyamoto Musashi was! Nevertheless, let’s put skepticism and cynicism aside and do what we came here to do: study the life of Miyamoto Musashi(as best we can).

The Life of Miyamoto Musashi

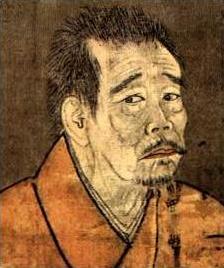

Miyamoto Musashi was most likely born in 1584 in either Mimasaka or Harima in western Japan. His father(or possibly his adoptive father) is believed to have been Shinmen Muni, a shōgunate-approved military tactician skilled in the art of the Jitte―a small metal truncheon used in close combat battles during the Edo era.

According to the Gorin no sho, Musashi went by the name ‘Shinmen Motonobu’. The origin of the name ‘Miyamoto Musashi’ is unknown. One source states he was born in Miyamoto village in Mimasaka. He also refers to himself as ‘Musashi no kami’―a title awarded to the governor of the Musashi province of Japan. Whether he was actually awarded this title or not is also unknown. While it wasn’t uncommon for samurai to award themselves unofficial titles to help lay claim to territories they had their eye on, Musashi’s status was presumably far too low for him to have been considering such a thing. At any rate, while it is possible Musashi at some point went by the name ‘Miyamoto Musashi’, it’s more likely he referred to himself as Shinmen Motonobu.

Like most swordsmen, he started out training with a bamboo sword. Unlike most swordsmen, though, he broke every one of his swords with just one swing and had to upgrade to the aforementioned wooden sword that he would continue to use throughout most of his career.

As his father had been serving the Kuroda family since before Sekigahara, it’s possible Musashi participated in the battle. However, if this was in fact the case, there are no sources available to suggest whether he fought alongside Kuroda Kanbei at the battle of Ishigakibaru or whether he joined Kanbei’s son, Nagamasa, at Sekigahara itself.

At the age of 21, he fought a series of bouts against the Yoshioka―a renowned family of sword masters who had been employed as personal instructors of the Ashikaga shōgun family for generations. Musashi claims he won all three of the fights that supposedly took place, but other documents dispute this claim. We’ll take a closer look at this later.

Verifiable sources teach us that Musashi did, indeed, participate in the siege of Ōsaka, fighting alongside the shōgunate’s army. In 1626 he adopted a son, Iori, and together they helped to put down the Shimabara rebellion. Musashi was already supposedly 53 years old at the time and apparently sustained an injury during the battle, the extent of which is unknown.

After Shimabara, Musashi remained in Kyūshū, where he was invited to live as a guest in Kokura han by the Hosokawa clan. He was offered a stipend of 5kg of rice a day―enough to feed seven men. This essentially gave him tacit consent to hire up to six servants. He was also provided with an additional rice supply which could be accessed in cases of emergency. This was an exceptionally rare level of hospitality for a guest.

Shortly after moving to Kokura, retainers of the Hosokawa clan began swarming towards Musashi, begging to be made his disciples. Musashi took them on and began teaching his dual-blade technique of sword fighting which he had learned from his father. This involved holding a long tachi blade in the right hand and a shorter dagger in the left.

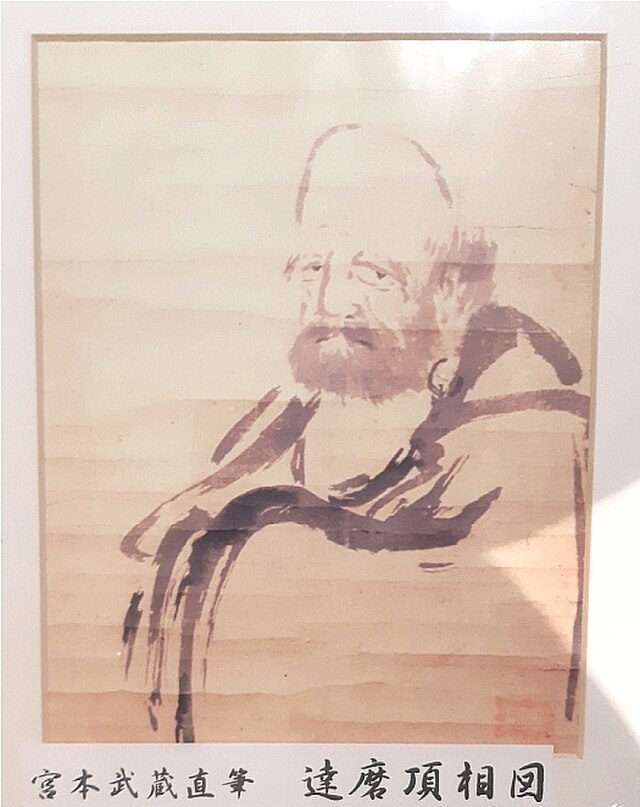

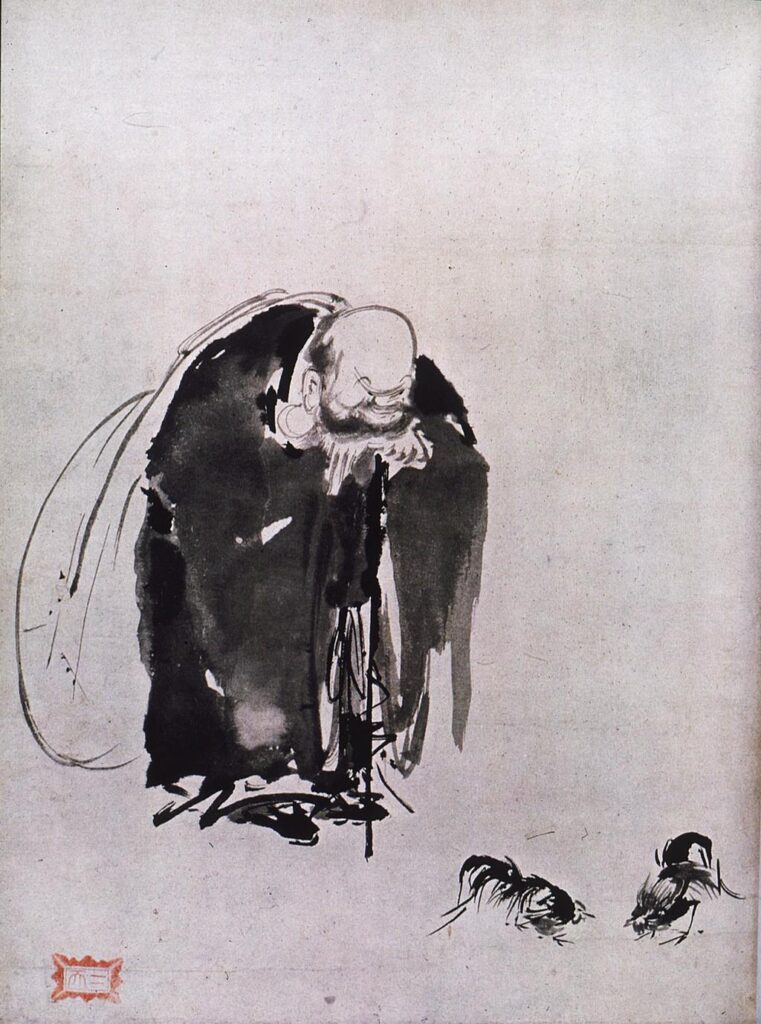

When Musashi wasn’t teaching, he enjoyed painting. Many of his works remain today and can be viewed in various museums around the country. It was also around this time he began writing the Gorin no sho. Musashi continued painting, writing and teaching in Kokura until he died in 1645 at the age of 62.

The Yoshioka

Returning to our analysis of Miyamoto Musashi’s legacy, let’s take a look at his two most famous and most widely documented battles. The first is a series of three fights that occurred between Musashi and the Yoshioka family, owners of one of the most highly acclaimed schools in Kyōto at the time. Musashi alludes to this event in the Gorin no Sho but doesn’t actually mention the name ‘Yoshioka’; he simply writes that he won several bouts against a famous military tactician.

His son, Iori, however, gave us a little more to go on: The Kokura monument―a large stone tablet erected shortly after Musashi’s death containing a detailed report of his most famous accolades. It’s this monument where we find the details regarding Kyōto and the Yoshioka. It also corroborates Musashi’s claim that he obtained a perfect victory against the Yoshioka. However, the information carved into the monument is believed to be highly exaggerated and, in places, completely made up. For example, it claims the third battle to have been an ambush conducted by several hundred of the Yoshioka’s students, who surrounded Musashi with bows and arrows. Musashi supposedly single-handedly defeated the entire group, destroying the school and wiping them out from later history. I think we can all agree that while Musashi may have been a master swordsman, he was still just a man; no one man can take down an army of 300-plus men by himself! While Iori’s heart was in the right place, he probably should have put a little more work into making his account of his father’s life more believable.

Gorin no Sho and the Kokura monument aren’t the only accounts of these battles. There are six sources in total, and they all give different reports as to the identity of Musashi’s opponents and the results of the three fights. Let’s sum them up…

First fight | Second fight | Third fight | Fate of the Yoshioka |

3 sources – Victory for Musashi | 3 sources – Victory for Musashi | 2 sources – Victory for Musashi | 3 sources – Discontinuation of the school |

3 sources – Draw | 1 source – Victory for Yoshioka by forfeit(Musashi didn’t show up) | 1 source – Musashi escaped an ambush | 3 sources – Continuation of the school |

1 source – No information | 3 sources – No information |

Of course, you have to take into account factors such as when each report was written and who it was written by, but even after having been studied by numerous researchers for centuries, historians are still left baffled as to what actually occurred between Musashi and the Yoshioka. Anything short of the discovery of a report written by a shōgunate official will most likely keep this mystery preserved for all time.

Ganryūjima

And now we come to Musashi’s most famous accolade: Ganryūjima―the legendary battle against acclaimed sword master Sasaki Kojirō. Similar to the Yoshioka situation, different sources give different accounts of the battle that took place at Ganryūjima. In fact, these accounts are so contradictory in places, virtually nothing can be confirmed about Sasaki Kojirō, including his name, age, status or even why he wanted to fight Musashi in the first place. Early sources refer to him only as ‘Ganryū’, the name of the fighting style he adopted. The name ‘Sasaki’ first appears in a kabuki performance written in 1737 and was later adopted as historical fact by the Nitenki in 1776. Whatever his actual name might have been, the term ‘Ganryū’ is used to refer to him consistently throughout all sources. Shortly after the battle, the name of the island on which it was fought was changed from ‘Funajima’ to ‘Ganryūjima’ in honour of Kojirō.

So what does the man himself have to say about the most epic battle of his life?… Nothing! Gorin no sho makes no reference whatsoever to either Ganryūjima or Kojirō! But what does this mean? Did the battle not happen? Did Musashi want the battle struck from history for some reason? Did he feel some kind of guilt?… Shame?… What reason could he possibly have to leave no record of it? Unfortunately, there isn’t a definitive answer to that question; it’s just one of the many mysteries Miyamoto Musashi left behind. Despite the fact he openly and regularly discussed the details of his Yoshioka endevours with his students, he rarely spoke of Ganryūjima. The few times he did speak of it, however, are recorded on the Kokura monument as well as in the Bukōden and the Nitenki. Other sources give accounts of events passed down by locals to their children and grandchildren. Theoretically, the older the source, the more accurate it should be. With that in mind, let’s take a look at the oldest account of the event we have. What did Iori have to say about his adoptive father’s fight on the Kokura monument?

A skilled tactician by the name of Ganryū challenged Musashi to a formal duel. Musashi agreed to the fight but informed Ganryū that while he was free to use whatever weapon he desired, Musashi himself would be using a wooden sword. Both men agreed to the terms and the location: Funajima, a small island located in the middle of the ocean on the border of Nagato and Bunzen. Ganryū wielded a 3ft long blade. He was swift and displayed good form, but Musashi’s reflexes were lightning fast. He struck Ganryū once with his wooden blade, and Ganryū fell dead. The island later became known as ‘Ganryūjima’.

A simple and plausible depiction but perhaps not entirely accurate; reports from locals explain how regardless of the fact both men agreed to approach the island alone, Musashi hid a number of his disciples some distance away. The strike described on the Kokura monument didn’t kill Kojirō but rather knocked him out. After Musashi departed from the island, his disciples left their hiding spot and finished the job. As Musashi neared land, Kojirō’s men chased him by boat, firing arrows and forcing him to flee to Bungo, where his father sheltered him. These reports were handed down from generations of locals over the course of 100 years. Their validity is questionable, but if they are true, they explain Musashi’s reluctance to discuss the fight with even his closest disciples.

That brings us to the Bukōden―the version of the tale on which both Yoshikawa Eiji and Japanese television based their stories. This one deserves to be told in as dramatic a manner as possible, so with that being the case, allow me to add my name to the long list of authors and script writers who have attempted to depict Miyamoto Musashi’s greatest accolade…

The Battle of Ganryūjima – A novelisation

Musashi’s heart was still. He attempted to steady it by focussing on the rhythm of the waves, which were uncharacteristically calm. He wasn’t nervous; rather, overstimulated. This was the day he had been waiting for. Weeks had passed since he first contacted his father and had him use his contacts in the Matsui clan to arrange the meeting. Ever since he received confirmation from Matsui Okinaga that Hosokawa Tadaoki, the head of the Hosokawa clan and lord of Kokura castle, had agreed to the arrangement, his heart had been beating faster than usual. For most people, this increased heart rate was so minor, it would have gone unnoticed, but Musashi was sensitive to even the slightest change in his body’s condition. He had been keeping mental notes of any change he deemed significant. When facing a master the likes of Ganryū, even the smallest of fluctuations in bodily rhythm could prove fatal.

Sasaki Kojirō had started out his career as the sparring partner of Toda Seigen, renowned sword master of the Asakura clan in Echizen. Quickly realising his own talent, he took the name Ganryū and decided to become independent at the age of eighteen, heading out west in search of a daimyō who would take him on as a retainer. Word of his skills reached the Hosokawa in the far west of Kyūshū, and Kojirō was invited to stay in the castle grounds.

Word reached Musashi in the capital too. Shortly after Kojirō embarked on his journey out west, Musashi followed, honing his skills along the way in preparation for what he anticipated would be the most challenging duel of his life to date. He had fought all manner of weapons experts; even faced the infamous Yoshioka school of swordsmanship, led by descendants of men who had been handpicked to train shōguns throughout the Muromachi era. This time would be different though; among the many legends surrounding Kojirō, the one that piqued Musashi’s interest the most was the fact that he used a three-foot-long sword – a full four inches longer than the average blade. This difference in reach would force new tactics. Musashi would have to rely on a whole new toolbox if he was going to have the speed and agility to evade this formidable weapon.

He did have one advantage over Kojirō, however: age. 29 years of life experience and 16 years of combat gave him an edge over the young sword master. But Musashi wasn’t seeking an edge; where would be the fun in defeating a legend on an uneven playing field? He clutched the wooden sword he had carved less than an hour before from the stern of a small sailing boat that had been given to him by Uemon, a local dealer who had put him up for the night. This would be his equaliser. Three feet of steel versus a piece of old oak. Musashi couldn’t accept any less of a victory.

As the boat approached the shore of the small island, he was able to make out the silhouette of a tall man wearing a noshime and hakama. He must have been almost six feet in height. Upon catching sight of Musashi, he sheathed his sword and began to tie his hair up, repositioning himself 50 feet from the shore on a flat, hard area of grassy earth – much easier to fight on than the moist and sandy beach. Minutes later, Musashi’s boat docked and the two warriors’ eyes met for the first time. Until that moment they had been simply legends in each other’s mind – fictitious figures based on exaggerated stories told by people who knew little of what it meant to be a sword master. It was time to separate fact from fiction. Kojirō stood poised, his hand on his grip, waiting for his opponent to step into range of his voice.

“You’re late.”

This was true. It had taken the messenger sent from Kokura three attempts to wake Musashi from his sleep. When he eventually succeeded, Musashi, despite already being late for the battle, indulged in a leisurely breakfast before carving his weapon and finally setting off. Frustrated from the long wait, Kojirō drew his sword and hurled the sheath into the water.

“You just acknowledged your defeat,” Musashi smirked. “If you held any hope of winning, you would still have need for your sheath.”

Furious, Kojirō lunged at Musashi, striking him between the eyes and slicing his hachimaki. It floated gracefully to the ground below them. Before it could land, however, Musashi had already made his counterattack, landing a powerful blow to Kojirō’s head with the hard wooden blade. The young master stumbled back and collapsed, semi-concussed. Through blurred vision, he could barely make out his opponent’s looming figure approaching him. One desperate swing of his blade sliced through Musashi’s awase, cutting the thin material from his knee to his thigh but failing to find flesh. Musashi responded with a blow that landed just below Kojirō’s armpit. The sound of splitting bone was the last thing Ganryū heard before falling unconscious.

Musashi sat by Kojirō until his dimming breath became inaudible. He checked his nose and mouth for confirmation. Ganryū was dead. Another victory for Musashi. But this wasn’t the result he had been seeking. He could imagine the tales that would be created for decades – even centuries – to come surrounding the epic battle fought at Funajima between the two legendary sword masters. But he knew the truth; Kojirō wasn’t the opponent he had been seeking. Would anyone ever be able to give Musashi the definitive result he had longed for all these years? One final victory that would saturate him for a lifetime; the victory he himself could create legends about; the victory that would allow him to hang up his sword and replace it with a brush. Musashi made his way back to the boat. The search would have to continue a little longer.

Summary

Well… that wasn’t quite Yoshikawa Eiji quality, but I did my best. Thank you to all who took the time to read it rather than skip to the summary. As for the summary… I’m not quite sure how to sum up the life of a man we know almost nothing about. If, at the very least, I’ve managed to convince you that there’s no way to know anything for sure about Miyamoto Musashi, I’ve done my job.

I will, however, leave you with one pet theory I have regarding Musashi’s popularity. You see, Musashi isn’t the only mysterious figure in Japanese history who managed to become a household name despite the lack of evidence regarding his exploits. There are others. Two that come to mind are Ikkyū and Sakamoto Ryōma. The former was a zen priest known for his quick wit, humour, and unpriest-like antics. For many of you, I’m assuming the latter needs no introduction. Sakamoto Ryōma is one of the most famous figures of Bakumatsu and is widely acknowledged as being the man responsible for the assembly of what would become the current Japanese government. However, what some of you might not know is that until acclaimed historical author Shiba Ryōtarō wrote a novel depicting Ryōma’s life in the 1960s, most Japanese people had never heard of him.

So what do these two men have in common with Musashi? They lived adventurous lives, travelling across the country on journeys of self-discovery as they worked towards their goals. The further they ventured, the further they spread their name. Their free spirit and charm most likely helped them to remain in the minds of the people they met, and as those people passed their stories on to friends, they became increasingly exaggerated and varied to the point no one could tell which parts were true anymore.

Fast forward a few hundred years and you have a nation of blue and white collared workers who dream of leaving their mundane jobs and embarking on adventures of their own. For most of them, this desire will never be anything more than a dream. So who do they turn to in order to live out their fantasies vicariously? Adventurers of a time long past; men whose exploits may not have been as exciting as people would hope, but who provide a canvas onto which people can paint their dreams. I’m pretty sure there’s enough space left on those canvases for their stories to unfold further over the next few centuries too. Miyamoto Musashi is not complete; he will continue to develop and assume the form of new dreams dreamt by generations yet to be born. One of my dreams is to live long enough to see the next stage of his evolution.