Japanese history overview Pt. 5: The Muromachi era Pt. 2

Congratulations on reaching part two of the Muromachi era overview. I had to split this one into two because there’s so much to get through. It’s such a complicated era, the majority of which consists of non-stop fighting for control of the shōgunate and, by extension, the country(which, to be fair, doesn’t differentiate it much from the era that came before it). Luckily, the Ōnin war provides the perfect cut-off point, as most historians agree that the end of the war marks the start of the Sengoku era. So let’s take our first step into Sengoku and find out what happened after the dust of the war settled. Once again, make use of Japan History’s map of ancient Japan whenever you need to.

The fallout of the Ōnin war

11 years of battles left the capital in ruins and the shōgunate defenceless, as the shugo who had lived in the capital since the start of the Muromachi era now had to return to their respective provinces to protect their land from the growing power of the deputy shugo, who, having seen how powerless the shōgunate was to put an end to two major wars, realised that there was no one to stop them from overthrowing the shugo and usurping their power.

Some of the shugo remained in Kyōto to help rebuild the capital and defend the shōgunate. However, the war had depleted their fortunes, armies and resources to the point there was precious little they could do to protect even themselves let alone the shōgun, who had now become a puppet of the kanrei, much as the emperor had became a puppet of the kanpaku back in the Heian era(history repeats itself). Powerless as the shōgun was, he remained a symbol of samurai culture, still respected by a number of the major families. For this reason, it was beneficial to have him on side; the little influence he had left could still give you an edge over the competition.

As the shōgunate had little money left to support the Imperial Family and the many nobles who remained in the capital, the court began selling off official positions and ranks usually reserved for high-ranking noblemen to samurai families. This led to occurrences of multiple people holding the same position at the same time. These positions were largely meaningless to samurai; they merely served as titles through which they could flaunt their status. However, on occasion, they did come in handy: although the shugo was the shōgunate-appointed governor of a province, the court had its own governerial position which had existed since the early 8th century. Although now meaningless, since the court officially outranked the shōgunate, obtaining this position provided samurai with an excuse to lay claim to certain provinces.

Yoshimasa and Yoshihisa

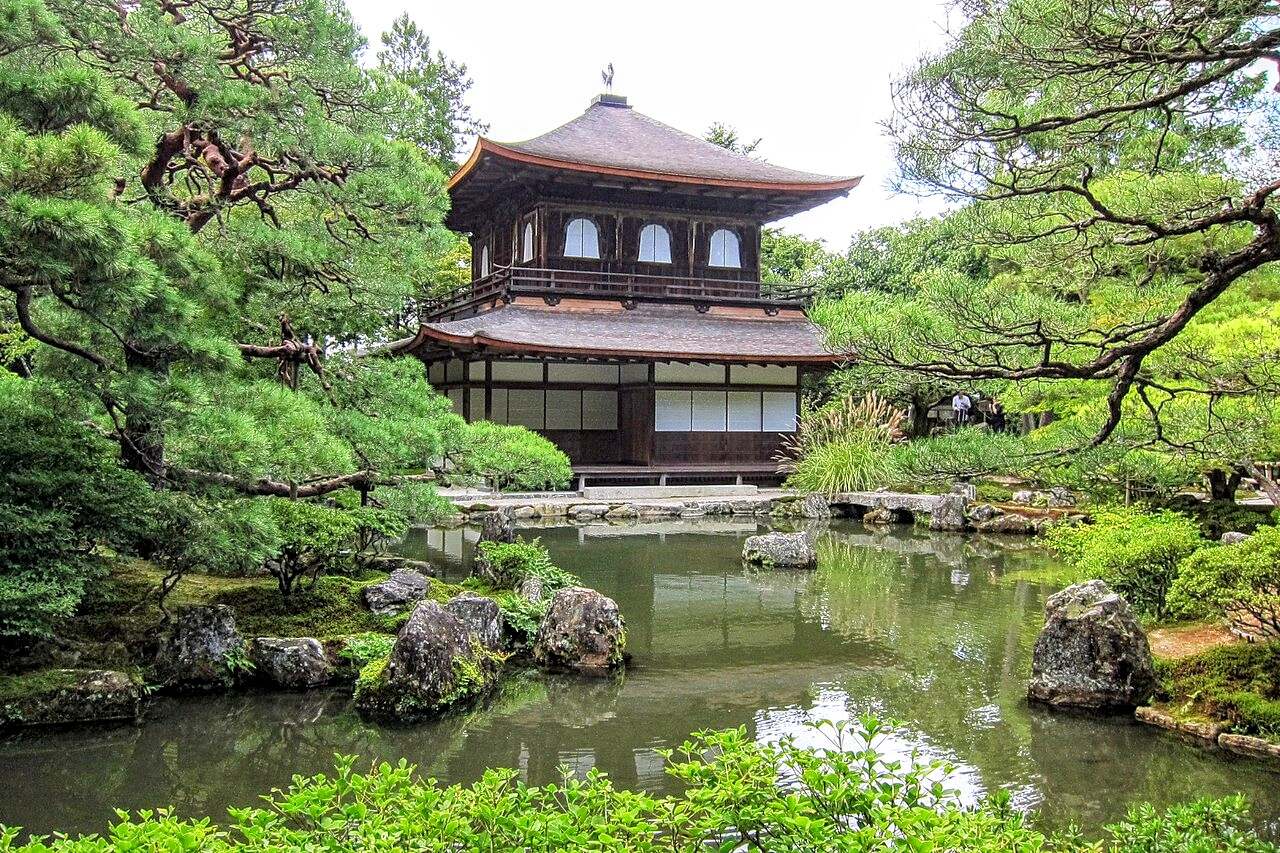

During the war, the shōgun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, passed his title to his son, Yoshihisa. As a retired shōgun, Yoshimasa should have been focussing his attention on rebuilding the capital and restoring the shōgunate’s power. However, perhaps due to the stress of the war, he began to shun away from politics and instead spent the bulk of his time immersing himself in his hobby of architecture. In his final years, he built a mountain retreat, Jishōji, which would become known as ‘Ginkakuji’, or the ‘Silver Pavilion’. Despite what its nickname suggests, the temple does not contain even the slightest scrap of silver; it was given this name purely to provide a contrast with the Golden Pavilion built by his grandfather 84 years earlier.

Yoshimasa’s disinterest in political matters led him to do very little to quell the mass poverty spreading across both the court and the samurai community, or put a stop to the small skirmishes that continued for some time after the end of the Ōnin war. For this reason, it took many decades before the capital could be completely restored.

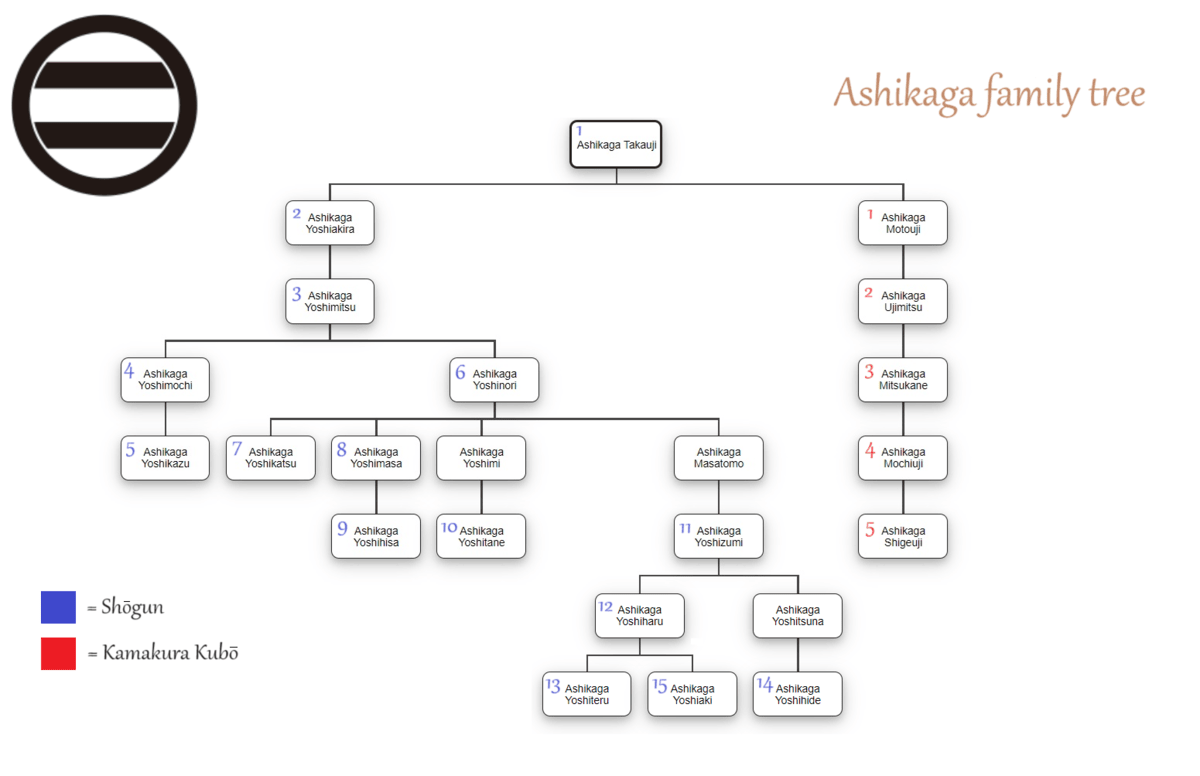

Yoshihisa too undoubtedly felt the pressure of the situation, as evidenced by the fact that he died in 1489 at the age of 23 due to alcoholism(the second shōgun of the period to have died of an alcohol addiction. If this doesn’t prove how stressful a time it was, I don’t know what does!). Having died without producing an heir, Yoshihisa was succeeded by his cousin, Yoshitane―son of Yoshiki, who, if you’ll remember, had originally been promised the title of shōgun by his brother. However, this decision didn’t sit well with the kanrei of the time: Hosokawa Masamoto.

Hosokawa Masamoto

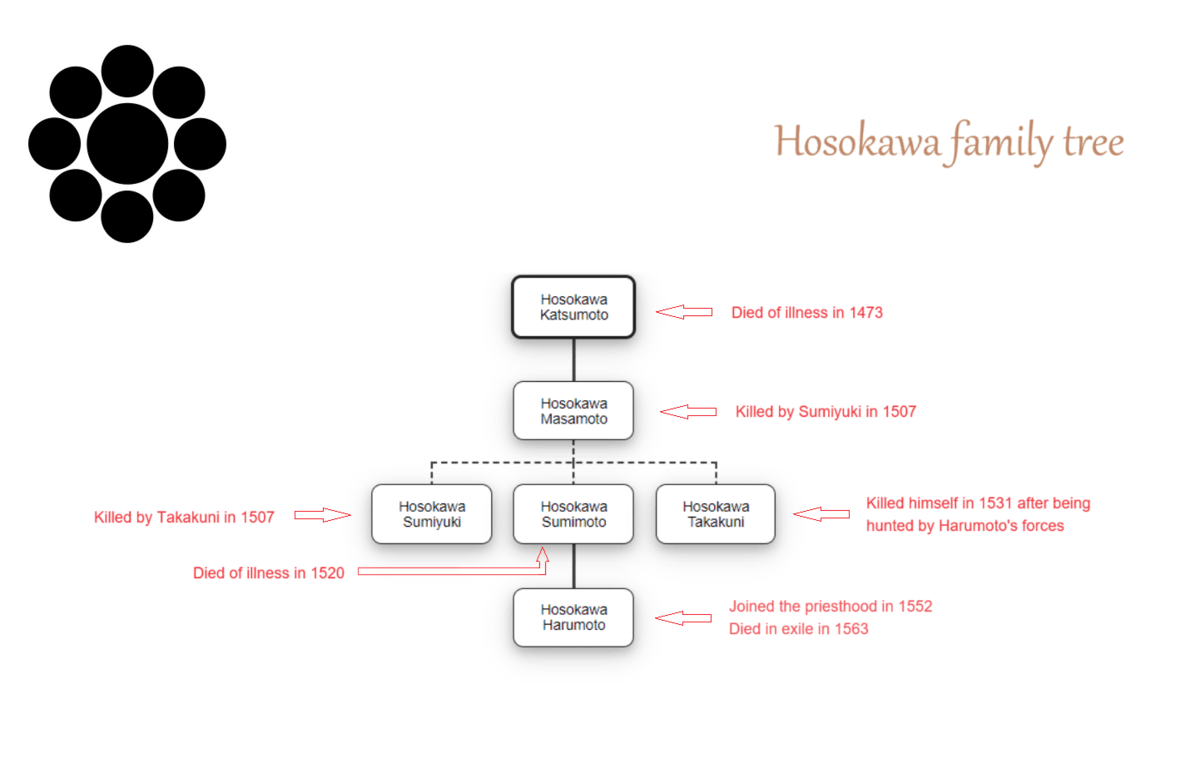

Since a fair amount of bad blood had formed between Masamoto’s father―Katsumoto― and Ashikaga Yoshiki during the Ōnin war, it’s not surprising that Masamoto didn’t want to see Yoshitane named the 10th shōgun. Others within the shōgunate shared his dissatisfaction. Luckily, though, there was another option: Ashikaga Yoshizumi, son of Masatomo, the Horigoe kubō. Yoshimasa, Yoshiki and Masatomo were all brothers, which meant that Yoshihisa, Yoshitane and Yoshizumi were all first cousins. The only problem was that Yoshizumi had entered the priesthood in order to avoid a succession dispute in Horigoe(sound familiar?).

This was no problem for the kanrei though; while Yoshitane was outside the capital trying to put an end to the fighting among the Hatakeyama(which was still going on despite the war having ended 15 years earlier!), Masamoto had him deposed and replaced with Yoshizumi, whom he swiftly had return from the priesthood and reinstated into the Ashikaga family. Yoshitane led his army back towards the capital and faced off against Masamoto in a bid to regain his position, but was forced back by the power of the shōgunate army and left with no choice but to roam the neighbouring provinces in search of new allies. Eventually, he took refuge under the Ōuchi in the far west.

Yet another succession dispute

With his new puppet secured on the shōgunate’s throne, Masamoto had became the most powerful man in the country. He was so powerful that he began to be nicknamed the ‘Half Shōgun’―although in reality he had already amassed greater power than most of the shōguns up until that point could ever have hoped to achieve. The only problem that stood in the way of his being able to carry this privilege on to the next generation was the fact that he wasn’t able to produce an heir. This wasn’t due to any social or biological factors, but rather the fact that Masamoto followed a unique and ancient religion known as Shugendō, which taught that if a man were to refrain from female ‘interaction’ for the first forty years of his life, he would obtain powers akin to those of a wizard. The nature of these powers as documented in history books are annoyingly vague, although certain texts do make mention of the ability to fly. Whatever the identity of the powers, though, in order to obtain them, Masamoto remained abstinent all his life(although he did engage in relationships with men. This was common in samurai society, but some historians still believe Masamoto’s belief in Shugendō was merely an excuse to cover the fact he was homosexual).

Unable to obtain an heir through usual means, Masamoto adopted a son, Sumiyuki―a cousin of the shōgun’s mother. This allowed him to strengthen ties with his newfound puppet even further. All would have been okay had it ended there, but a number of Masamoto’s retainers were unhappy with a relative of the Ashikaga heading the Hosokawa brand. And so, in order to appease this faction, Masamoto adopted a second son from a branch of the Hosokawa family. To make matters worse, several years later he adopted a third son from yet another Hosokawa branch! Even peasant farmers could have predicted the inevitable succession dispute at this point.

Worried that he’d lose his position to one of his younger brothers, Sumiyuki killed Masamoto and took his place as head of the family. His reign didn’t last long, however, as his youngest brother, Takakuni, swiftly avenged his father. At first Takakuni and his remaining brother, Sumimoto, were cooperative. However, conflict between certain members of their respective cliques within the clan had a drastic effect on their relationship. With Masamoto dead and the two remaining Hosokawa brothers at each other’s throats, Former Shōgun Ashikaga Yoshitane decided the time was ripe to lead the Ōuchi army back to the capital and reclaim his empire.

Yoshitane’s revival

Upon arriving in the capital, Yoshitane struck a deal with Takakuni, who had him reinstated as shōgun. This began a tag-team battle that pitted the two against Sumimoto and Yoshizumi. The war raged on for several years until in 1511, Yoshizumi died of illness. After that, Takakuni continued fighting his brother while making it clear to Yoshitane that he was nothing more than a puppet. Yoshitane eventually grew tired of this arrangement and abandoned the capital in 1521. He was quickly deposed by Takakuni and died one year later. Yoshizumi’s son, Yoshiharu, was named the 12th shōgun.

Sumimoto died of illness in 1520, passing the responsibility of the ongoing dispute to his son, Harumoto. Harumoto finally defeated Takakuni in 1531 and forced him to kill himself. So with his biggest rival eliminated, Harumoto now had control over the country, right? Nope! Sengoku isn’t that kind. If you destroy your enemy, Sengoku’s only reward is a stronger enemy. In this case, Harumoto’s chief retainer: the Miyoshi clan. Disputes over whether or not to support Yoshiharu as shōgun created a rift among Harumoto’s council that led to almost 20 years of fighting in which three major religions participated: Tendai-shū, Nichiren-shū and Jōdoshin-shū. In 1546, amidst this new war, Yoshiharu escaped to the Ōmi province, where he passed the title of shōgun to his son, Yoshiteru, before dying four years later.

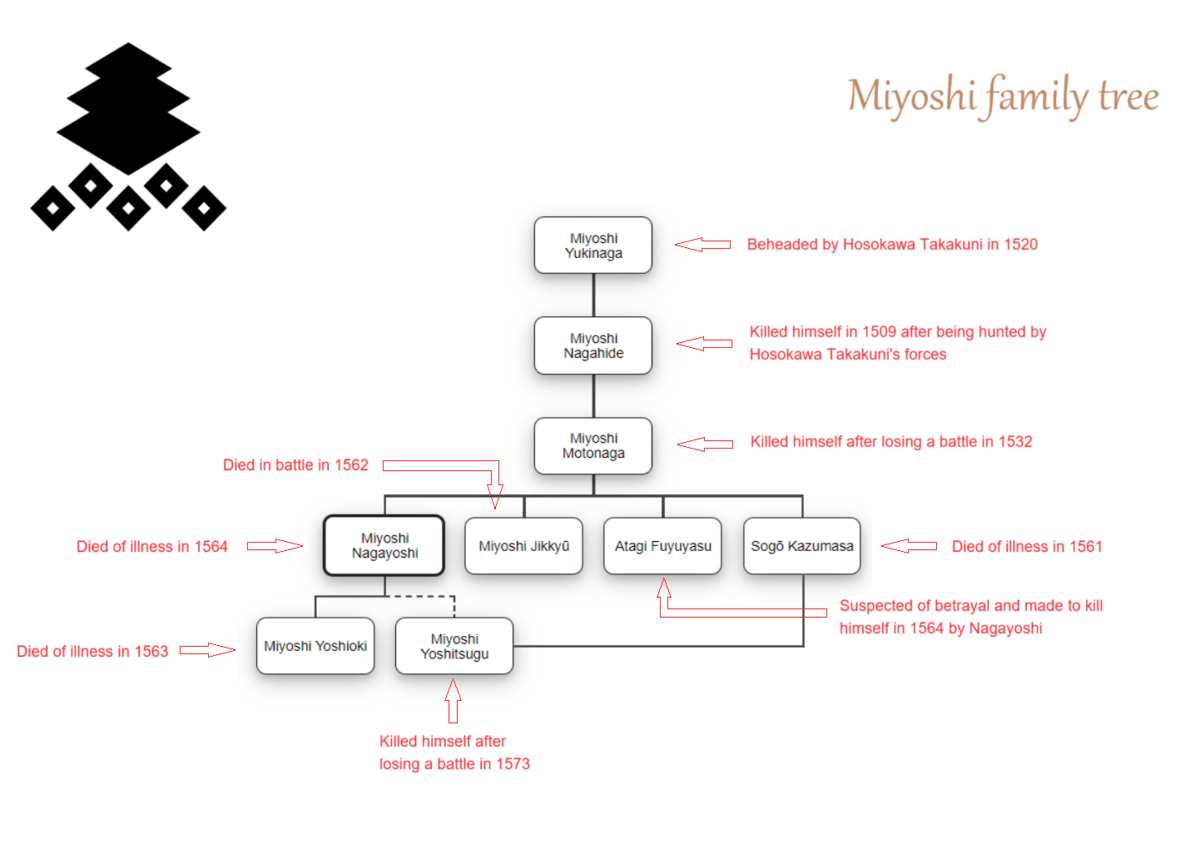

Miyoshi Nagayoshi

In 1549, disputes among the Miyoshi clan were finally settled. Miyoshi Nagayoshi took charge of the family and subdued Harumoto, propelling himself to the top spot in the Sengoku rankings. Harumoto responded by teaming up with Ashikaga Yoshiteru to try to oppose Nagayoshi but finally gave up in 1561. He negotiated Yoshiteru’s return to the capital in exchange for his surrender. Nagayoshi confined him to a temple, where he died two years later. With the majority of samurai families in Yamashiro, Kawachi, Settsu, Izumi and Yamato―the areas of Japan that now make up Kyōto, Ōsaka and Nara―now under his umbrella, Nagayoshi became the first champion of Sengoku.

At this junction, I should address any concerns that may have surfaced with regard to my having skimmed over almost fifty years of epic family feuds and religious warfare. There’s a very good reason for it: none of this is the A story. It isn’t even the B story! Very few people in Japan know anything of the events I’ve briefly explained in the last few hundred words. I guarantee you that less than 10% of the nation knows the name ‘Miyoshi Nagayoshi’, and less than 1% will have heard of ‘Hosokawa Masamoto’. Incredible as their stories may have been, very rarely are they adopted as the subjects of dramas, movies or novels. They don’t even feature in some Sengoku games! The exploits of the Hosokawa and Miyoshi were overshadowed by the far more interesting developments that were occurring in the east of the country at the time. Let’s put Miyoshi Nagayoshi and his conquering of the capital aside for now and take a brief look at the B story.

The Hōjō

Hōjō Sōun

The Ōnin war affected the shugo of various provinces in a number of ways. In the case of Suruga, the shugo at the time, Imagawa Yoshitada, was killed by one of his retainers who switched sides at the very end of the war. As Ujichika, his three-year old son, was too young to take charge of the family, the Imagawa were left puzzling over who to select as an interim until Yoshitada’s heir came of age. Eventually, they came to the decision that Ujichika’s cousin, Oshika Norimitsu, would lead the family for the following ten years, after which time he would hand over control to Ujichika.

However… (you guessed it)… Come 1487, Norimitsu refused to relinquish his position. Luckily, though, Ujichika’s mother had a brother in the shōgunate. Ise Shinkurō worked directly for Ashikaga Yoshihisa, entertaining and hosting guests who came to visit from outside the capital. After his death, he would come to be known by a different name. For now, though, he was a mysterious shōgunate official, much of whose early life is unknown. Modern historians agree that Ise Shinkurō was most likely the name by which he went while he was alive. But for the purpose of consistency, I will be referring to him in this blog using the name by which he is most familiar: Hōjō Sōun.

The Imagawa were a high-ranking samurai family with an ancestral line leading back to the Minamoto, and, by extension, the Imperial Family. The fact that Sōun’s sister was married to their leader suggests that Sōun himself hailed from a family of status. After obtaining permission from the shōgunate, he travelled to Suruga and took charge of the Imagawa army, advancing them on Norimitsu’s land, defeating the enemy army and forcing its leader to kill himself. As a reward for his actions, he was granted control of Kōkokuji castle, located on the border between Izu and Suruga.

Chachamaru

Speaking of Izu, if you’ll remember back to part one of the overview, Ashikaga Masatomo set up shop in a small of area of Izu known as Horigoe in 1458 after being refused entry to Kamakura. As we’ve already seen, Masatomo’s son, Yoshizumi, eventually went on to become shōgun. However, Masatomo had two other lesser-known sons, the older of whom, Chachamaru, he apparently hated to the point where he would torture him and lock him in a dungeon for lengthy periods of time. There is little verifiable history to back these claims up, but when you consider the fact that in 1491, just three months after his father’s death, Chachamaru killed his youngest brother and step-mother, it’s not that big a stretch of the imagination.

Needless to say, Yoshizumi was not happy about his mother’s murder. So one of the first things he did upon becoming shōgun was set Sōun on Chachamaru. Being situated on the border of Izu and having a track record of removing unwanted elements from their positions, Sōun was the logical choice for the job. This would take a fair bit more work than it had taken to bring down Norimitsu, though; the Horigoe kubō had a lot of support spread out across the entire Izu peninsula.

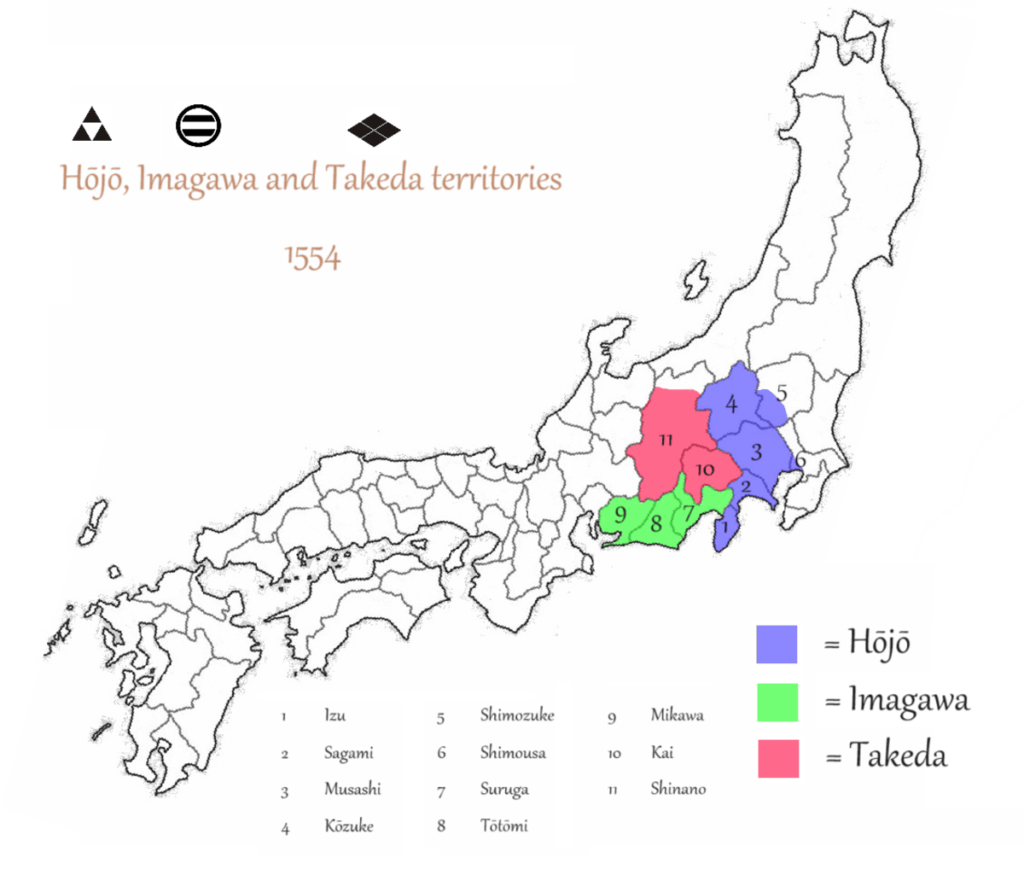

Not everyone was as enthusiastic about the new kubō though; Chachamaru was less than popular with a number of his chief retainers. It didn’t take much persuading to convince them to switch sides. Five years after turning Chachamaru’s allies and killing those who remained loyal to him, Sōun succeeded in eliminating his target and adding Izu to his territory portfolio. With several castles now under his command, he used Izu as a base to become involved in the Uesugi family’s feud, which gave him a foothold in Sagami. In 1516, three years before he died, he drove the Miura clan out from the Miura peninsula, giving him control over the entire province.

Hōjō Ujitsuna

Sōun’s son, Ujitsuna, moved the family’s base to an area named Odawara and changed his surname to Hōjō. Those of you who have studied the Kamakura era will remember that Hōjō is the name of the family that supported the shōgun as shikken before usurping his power and taking full control of the shōgunate. Ujitsuna’s intent was to gain the support of the local clans by changing his name to that of the most powerful family that had ever lived in the area. In order to distinguish between the two families, history remembers this new Hōjō family as the ‘Later Hōjō’.

During his lifetime, Ujitsuna expanded the Hōjō empire, attacking the Uesugi and gaining half of the province of Musashi. Elsewhere, in 1517, the Imagawa succeeded in defeating the Shiba to gain control of Tōtōmi. In 1536, another Imagawa succession dispute broke out. Ujichika’s third son, Yoshimoto, emerged victorious. However, during the dispute, Yoshimoto joined forces with the Takeda, with whom his family had been enemies for many years. Fearing that the Imagawa would begin to rely more heavily on the Takeda and eventually cut off ties with the Hōjō, Ujitsuna decided to turn on Yoshimoto and start a war with the Imagawa. The three families continued to lead a complicated relationship for the next twenty years, forming and breaking alliances with each other until finally, in 1554, they married their daughters to each other’s sons and formed a powerful three-way alliance. This allowed the Hōjō to expand out north and east, the Imagawa to expand out west, and the Takeda to expand north and west without fear of being attacked from the opposite directions. In time, all three would become top tier daimyō of the Sengoku era.

Oda Nobunaga

Now we come to the A story―the beginning of the end of the Muromachi era at the hands of arguably the most famous man in all Japanese history. While the Hōjō, Imagawa and Takeda were busy working out the fine details of their agreement, Oda Nobunaga was systematically taking down every layer of government above him in his home province of Owari. By 1560, he had control over the majority of the region. This, however, left him vulnerable to attack from more powerful daimyō; rather than having to take down a number of small local castles one by one, all they had to do was defeat Nobunaga, and they would be able to add Owari to their empire. This situation was extremely appealing to one man in particular: Imagawa Yoshimoto. Having conquered Tōtōmi and having gotten most of the major families in Mikawa on his side, Owari was next on his list.

The Battle of Okehazama

Yoshimoto started his campaign west in order to confirm the situation regarding the forts he had set up to restrict the movements of the troops stationed at Nobunaga’s castles. Of course, he didn’t announce his intentions; he set out on his journey under the pretence of visiting the capital. Nobunaga was suspicious. When his spies returned word of Yoshimoto’s true intentions, he sent out scouts to determine the most likely location of Yoshimoto’s camp. They reported back that he was probably stationed at an area known as Okehazama. With the bare minimum of preparation and an army one tenth the size of his enemy’s, Nobunaga launched a sneak attack and took the head of Imagawa Yoshimoto. Samurai all over the country were stunned; a no-name countryside bumpkin of a daimyō had taken out one of the highest-ranking samurai leaders in the country!

This unexpected defeat set the Imagawa back decades and, needless to say, had a major effect on the three-way alliance. Just eight years later, the Takeda attacked and destroyed the Imagawa, taking over the greater part of their territory. Let’s not dive any further into the Takeda’s part in this story, though, because we still have a lot to cover with Nobunaga. Before we return to him, however, allow me one final digression back to the capital, where the Miyoshi’s rule was starting to come undone.

The downfall of the Miyoshi

Unlike the Hosokawa―who ruined their claim to the country over decades of sibling rivalry―the Miyoshi brothers had always had a tight relationship. This relationship is what allowed Nagayoshi to become ruler of the capital and, ironically, it would also be what caused his rule to crumble. Between the years of 1561 and 1563, Nagayoshi lost his son and two of his brothers. This caused him to go a little crazy and kill his remaining brother, whom he believed was plotting against him due to false rumours being spread by some of his closest retainers. Perhaps due to the guilt of having killed his only surviving sibling, Nagayoshi himself died in 1564.

One year prior to his death, Nagayoshi adopted his nephew, Yoshitsugu, and named him his successor. Since Yoshitsugu was just 15 years old at the time, three of the Miyoshi clan’s chief retainers were chosen to support him until he was old enough to lead the household by himself. However, one more of Nagayoshi’s top retainers, Matsunaga Hisahide, opposed them. The three fought with Hisahide for years. In 1565, they joined forces with his son and killed the shōgun(Yoshiteru), who had been trying to restore power to the shōgunate. In 1567, Yoshitsugu defected to Hisahide’s side, and the three Miyoshi retainers contacted Yoshiteru’s cousin, Yoshihide, with a view to making him the next shōgun. Their plan was successful; Yoshihide was installed as the 14th shōgun one year later.

Ashikaga Yoshiaki

One more man had his sights on the shōgun position, however: Yoshiteru’s brother, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, who had been sent to join the priesthood at the age of three. Now 31 years of age, he believed he had a greater claim to the title than his cousin. After his brother’s death, he enlisted the help of some local samurai to escape the temple in which he was living, fearing that he might be the Miyoshi’s next target. He began to roam the neighbouring provinces in search of a daimyō powerful enough to support his claim to the shōgunate. For a variety of reasons, however, he was turned away from every door he knocked on. It was then that one of the samurai who had helped him escape mentioned that his cousin was married to an up-and-coming daimyō in the east of the country: Oda Nobunaga.

Nobunaga’s fame had not yet spread to the capital. Yoshiaki too was, as of yet, similarly obscure. Nevertheless, the two decided to take a chance on one another. The same year, Nobunaga fought his way through the province of Ōmi to get to the capital, where he defeated the Miyoshi three, forced them to flee their respective castles and installed Yoshiaki as the 15th, and final, shōgun of the Muromachi shōgunate. Having witnessed this incredible momentum, many local samurai swiftly decided to join Nobunaga’s cause. Among them were Matsunaga Hisahide and Miyoshi Yoshitsugu.

With Yoshiaki as his puppet, Nobunaga used the capital as a base to gain control over the surrounding provinces. However, Yoshiaki didn’t seem to fully grasp the fact that he was merely a puppet, and began trying to exercise more and more power within the shōgunate. Frustrated, Nobunaga put a number of restrictions on the shōgun, creating a rift between the two and putting an end to the honeymoon period of their relationship. Eventually, When Yoshiaki decided he couldn’t take it any more, he called on daimyō everywhere to storm the capital and take down Nobunaga. A number of major families, including the Azai, the Asakura, and the remaining members of the Miyoshi, took on the challenge.

After swatting off Yoshiaki’s minions for a couple of years, in 1573, Nobunaga succeeded in chasing the shōgun to his final hideout, where he defeated his army and banished him from the capital, ending the Muromachi shōgunate and the Muromachi era. Several months later, he defeated the Azai and the Asakura. Two months after that, he chased down Yoshitsugu and had him killed too. Thus began the Azuchi-Momoyama period and the undisputed rule of the greatest and most famous samurai lord who ever lived. Join me in part 6 of this overview for the continuation of this epic story.