Amaterasu – The True Identity of the Sun Goddess

For those of you who are new to Japanese history, I’m probably going to confuse the heck out of you with this one. For those of you who have a bit of background knowledge, I’m going to blow your minds twice during the course of this article. Not only am I going to introduce you to the most compelling theory I’ve ever come across regarding the identity of Amaterasu, but through the process of explaining the theory, I’m going to explain an even more compelling theory regarding the true age of the Japanese Empire. Before we get into either, though, for those of you who are completely lost, allow me to explain a little about Amaterasu and the Kojiki.

The Kojiki

To learn about Amaterasu, we need to look to the Kojiki—the oldest surviving historical record that details Japan’s history in its entirety from the time the country was created by the gods up until the middle of the 7th century.

Izanagi and Izanami

In the beginning, there was Takamagahara, a kind of heaven-like world in which a number of shapeless, formless masses of energy appeared. These were the earliest gods. As new gods came into existence, little by little they began to take more recognisable forms. The final two to appear were Izanagi and Izanami, whose forms were that of a man and a woman. They worked together to create the islands that now constitute Japan from the murky, swampy sea of matter directly below Takamagahara. Once they were done, they created a number of new gods to fill their new land with. These gods took the form of everything from grains of sand to people. However, when Izanami gave birth to Kagutsuchi, the god of fire, her body was so badly burned that she died.

Unable to let her go, Izanagi travelled to Yomi―the land of the dead―to try to find her. However, Izanami had already consumed food cooked in the fires of Yomi, essentially ensuring that she would never be able to leave. Her body had already decayed beyond recognition and maggots had made homes of her orifices. Terrified by her hideous new visage, Izanagi fled back to Yomi’s entrance and sealed it with a large rock. An infuriated Izanami screamed from behind the rock that she would curse 1,500 people a day to death, to which Izanagi replied that he would create 1,500 new people every day.

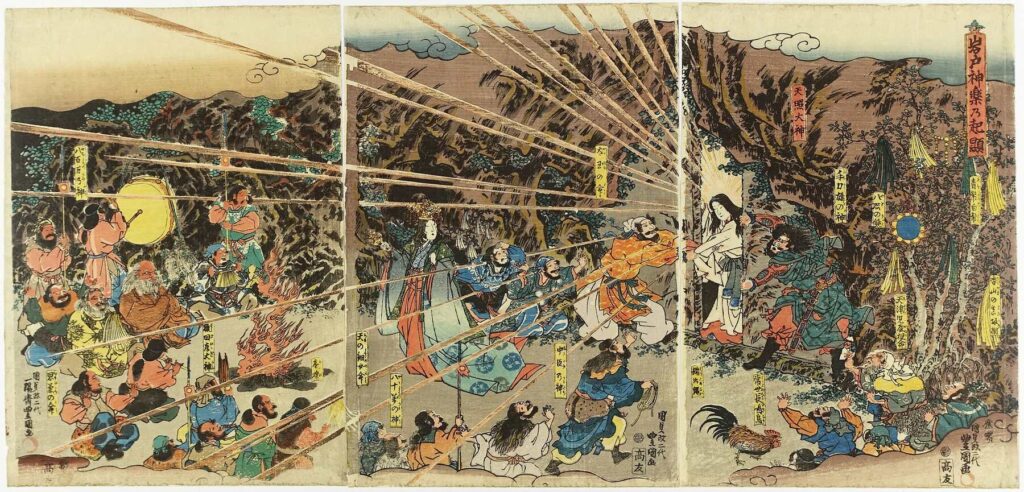

The Birth of Amaterasu

After returning from Yomi, Izanagi purified his body in a lake. As he washed himself, a number of new gods were born. Three in particular would go on to play major roles in the continuation of the Kojiki’s story. From his nose came Susanoo, to whom he awarded command over the seas. From his right eye came Tsukuyomi, to whom he awarded command over the night. And from his left eye came Amaterasu, to whom he awarded command over Takamagahara and, by extension, the sun. Amaterasu would go on to send her grandson, Ninigi, down to Japan to take command over the land Izanagi and Izanami had created. Ninigi’s great-grandson would later unite the country and establish the Yamato court, earning himself the title of first emperor of Japan―Emperor Jinmu.

Amaterasu’s Reign According to Legend

Hopefully, you now have some idea of just how important Amaterasu is to Japan. Even today she is worshipped by followers of Shintō as the greatest of all Japanese gods, and shrines across the country pay homage to her―not least of all, Ise Jingū, the largest and most visited shrine in all of Japan. Curiously, though, despite the level of devotion people now display towards her, Amaterasu ultimately makes very few appearances in the Kojiki. In fact, after sending her grandson to take over the Japanese islands, her name is barely mentioned at all.

How is it possible that a mythological figure whose name is mentioned a mere handful of times in an ancient text could have become such a religious icon? The phenomenon begs the question: is Amaterasu a representation of someone of importance who actually existed? If so, who? Naturally, it would have to be someone who doesn’t appear in the Kojiki. In order to figure out the prime candidate, we first have to figure out exactly when Amaterasu was presumed to have lived.

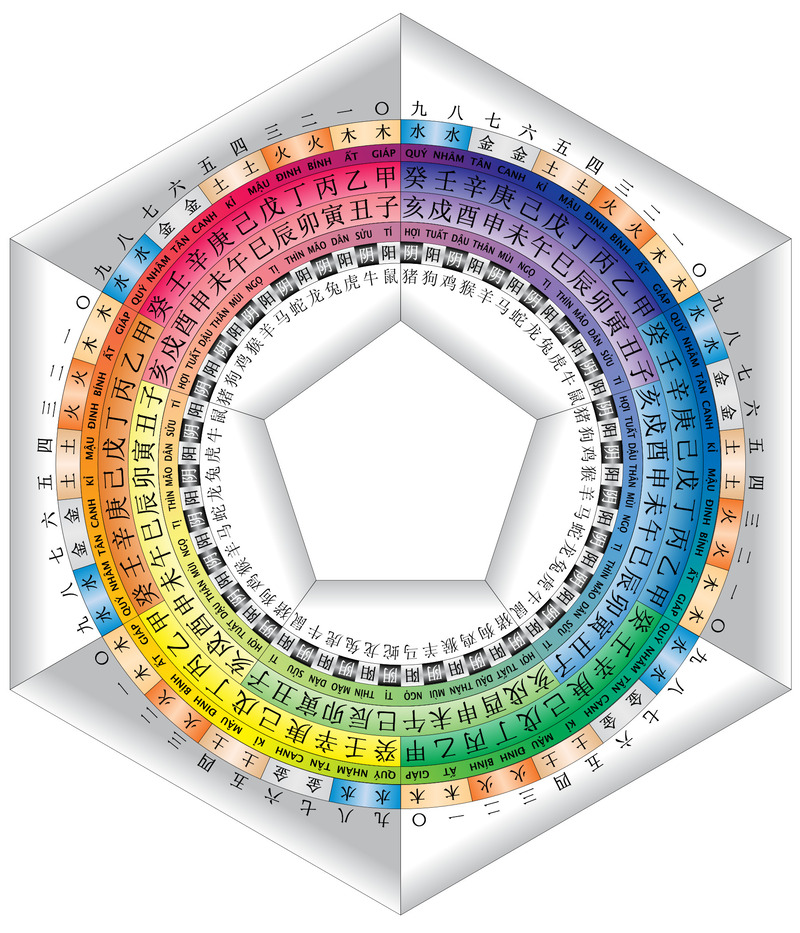

The Sexagenary cycle

To find out when Amaterasu lived, we need to consult the Chinese sexagenary cycle―a 60-year cycle that was created by combining the 12 heavenly branches(represented today as animals) with the 10 heavenly stems(represented as the elements), then taking the first 60 of the 120 possible combinations(since 60 is the least common multiple of 10 and 12). I won’t go into much more detail on the system itself or on its usage. All you need to understand right now is that when people talk about ‘the year of the monkey’ or ‘the year of the dog’, this is the system they are referring to.

Kanatotori

According to the Nihonshoki―a more detailed version of the Kojiki intended to be read by Tang China―Emperor Jinmu ascended the throne in the year represented in the sexagenary cycle as ‘kanatotori’(‘Xīn yǒu’ in Chinese). Calculating backward from verifiable dates recorded in the Nihonshoki using the ages of the emperors listed in both the Kojiki and Nihonshoki, the closest kanatotori to the period where Emperor Jinmu most likely lived was the year 660 B.C. However, archaeological excavations and anthropological studies have taught us that in this period of Japanese history, people were living in small, tight-knit communities in the middle of forests, hunting boars and foraging for nuts. Not only was Japan a far leap from having the manpower and technology necessary for someone to take over the country, but there was nothing in the country even worth taking over.

Putting aside the fact that people who lived during the time the Kojiki was written wouldn’t have known what life was like in 660 B.C., why was such an unlikely year chosen for the establishment of the Japanese Empire? One modern theory suggests a compelling reason for the decision. It explains that among the sixty years of the sexagenary cycle, kanatotori has an important meaning: it is one of two years that are suitable for a revolution. That being the case, it’s reasonable to assume that if a country wanted to rewrite its history, it would choose one of these years as the starting point. Furthermore, Taoism considers 21 repetitions of the 60-year cycle to be one unit of time. In other words, every 1,260 years, the world is ripe for a super revolution, the likes of which reshape it into a never-before-seen form.

A Super Revolution

Our next question must therefore be: what happened 1,260 years later? Fast forward to the year 601 A.D., and we find Shōtoku Taishi building his new palace in Ikaruga. During the following few years, he would go on to establish a constitution for the Yamato Court, create the Twelve Level Cap and Rank System and send envoys to Zui to form a trade agreement while asserting the court’s independence. In short, Shōtoku Taishi was attempting to revolutionise the country. In order to add weight to his revolution, he tampered with history to give Japan a new start date of 660 B.C.―the perfect year for the establishment of an empire in accordance with the rules laid out by Chinese philosophy and astrology.

This date was presumably documented in the Tennō-ki―a lost historical record of all emperors who lived prior to the 7th century, written by Shōtoku Taishi and Soga no Umako in 620―and passed down to Emperor Tenmu, who ordered the compilation of the Kojiki. Mind blown? Mine was when I first heard this theory. Compelling as it is, however, it is still just a theory. Given the fact that historians are divided on whether or not Shōtoku Taishi even existed, it’s possible that the whole thing was set up by Soga no Umako. It’s similarly possible it’s all just one big coincidence.

Amaterasu’s Reign According to Statistics

Returning to Amaterasu, now that we have a rough estimate for the era she was assumed to have lived according to legend, how do we go about working out the actual time period in which she(or whoever she represents) lived? Unfortunately, neither the Kojiki nor the Nihonshoki are much help with that; not only do they contradict each other with regard to the ages of the earliest emperors, but a number of the emperors recorded in both texts lived unfathomably long lives. Emperor Jinmu, for example, is documented as having lived to the age of 127! Emperors Keikō and Nintoku—12th and 16th emperors respectively—hold the joint record for longevity at a whopping 143 years!!

I suppose that can’t be helped though; if you’re going to claim your country is hundreds of years older than it actually is, you have no choice but to extend the lives of unverifiable historical figures in order to make the numbers fit. With no hint as to the calculation used to extend each emperor’s life, however(presumably, it was random), figuring out a reliable date for the ascension of the first emperor through Japanese texts alone is, unfortunately, impossible. And so we turn once more to China.

Tōkyō Imperial University’s Research

A study conducted at Tōkyō Imperial University in the late 19th century compared the reigns of Japanese emperors to those of Chinese emperors. If you take a look at the table below, you’ll most likely come to the same conclusion that they did: for any 400-year period throughout history, there is very little difference between the average reign of each country’s emperors. This makes China’s historical data a good base from which to calculate the actual reigns of all Japanese emperors listed in unverifiable Japanese texts.

Centuries | Japanese emperors’ average reign(years) | Chinese emperors’ average reign(years) | Difference(years) |

1st – 4th | ? | 10.05 | ? |

5th – 8th | 10.88 | 10.18 | 0.7 |

9th – 12th | 12.24 | 13.63 | -1.39 |

13th – 16th | 15.63 | 14.42 | 1.21 |

17th – 20th | 22.29 | 22.27 | 0.02 |

The first Japanese emperor whose birth and death can be verified is Emperor Yōmei, the 31st emperor, who reigned from 585-587 A.D. Applying the average reign of Chinese emperors from the 1st-4th centuries to all Japanese emperors who came before Emperor Yomei, we simply have to subtract 10.05 a total of 30 times from the year 585 to reach an estimated date for the ascension of the first emperor. The result is the year 283 A.D. Remember, though, Emperor Jinmu was a 5th generation descendant of Amaterasu. Therefore, we need to subtract 10.05 a further five times. This leads us to the year 233 A.D. If this number is to be believed, the Nihonshoki’s estimation for the establishment of the Yamato Court is out by 893 years!

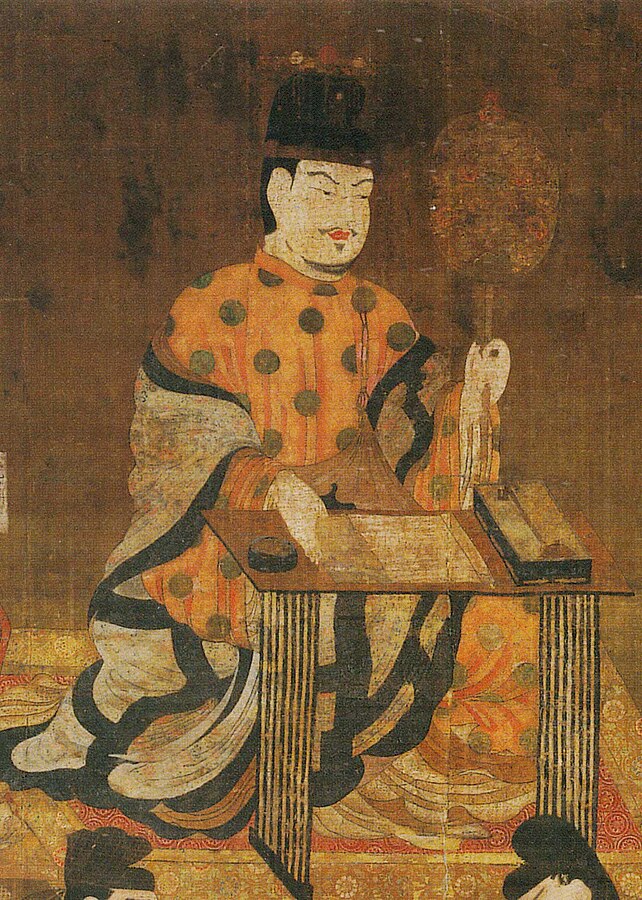

Amaterasu’s True Identity

Putting the inaccuracies of Japan’s ancient texts aside, let’s see what was going on in Japan in the year 233. Since Japanese texts can’t be trusted, we turn once more to Chinese history. This is where it becomes really interesting… The most verifiable texts of the time make reference to a sorceress by the name of Himiko, who ruled over a country called Yamataikoku, situated in the body of land now known as Japan. In the year 238, Himiko sent an envoy to China, which returned with gifts of 100 bronze mirrors and a golden seal acknowledging her as the ruler of Wa(the name by which Japan was known to China at that time). Himiko is made reference to a number of other times, her final mention documenting her death in the year 247 A.D

While the alignment of the dates alone is compelling enough evidence, it doesn’t end there; the Kojiki and Nihonshoki highlight a number of similarities between Amaterasu and Himiko. Let’s take a look at some of them…

Amaterasu | Himiko |

Object of worship in Shintō | Spritual leader of Yamataikoku |

Worshipped as the Goddess of the sun | Name can be interpreted as ‘hi no miko’, meaning ‘sorceress of the sun’ |

Never took a husband | Never took a husband |

Had two younger brothers | Had a younger brother and a young male servant who attended her |

Gifted a mirror which later became one of the three secred treasures of Japan | Gifted 100 bronze mirrors by Wei |

Hid inside a cave, sending the country into perpertual darkness | Total solar eclipse occurred once year before her death |

Daughter-in-kaw’s name contained a Chinese character that can be read as ‘Toyo’ | After her death, she was succeeded by a non-specific reative named ‘Toyo’ |

So, what do you think? Admittedly, some of the comparisons are a bit of a stretch, and convincing arguments can be made against a few of them, but all in all, when combined with Tōkyō Imperial University’s research, I think you’ll agree that the evidence supporting the theory that Amaterasu and Himiko were the same person is more than compelling. Hopefully someday more evidence will surface to give even greater weight to this theory. Until then, Amaterasu will remain one of Japan’s greatest mysteries.