Bakumatsu – the end of the shōgunate Pt. 2

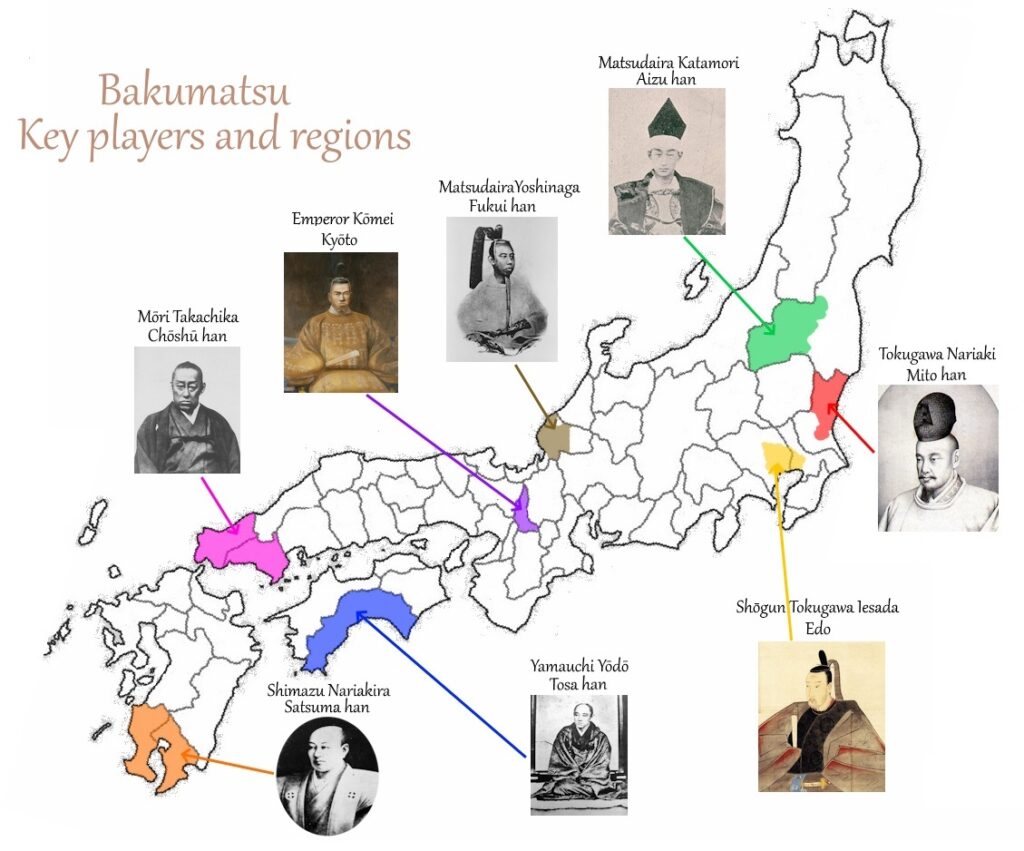

Welcome to part two of this coverage of Bakumatsu, arguably one of the most exciting times in Japanese history, detailing the downfall of the shōgunate and the samurai. In part one, we looked at how the arrival of foreign forces stirred up a panic in Japan, causing a number of social and economic problems that set off the whole chain of events. Satsuma han dominated the early part of the story. Today we begin in 1863, where the threat of British attack looms over Satsuma’s head and samurai all over the country, disillusioned with the shōgunate due to its indecisiveness, slowly but surely start to take the foreign threat into their own hands.

Chōshū han

In March of 1863, Shōgun Tokugawa Iemochi travelled to Kyōto to greet his new brother-in-law, Emperor Kōmei. Far from a friendly family visit, the emperor intended to cash in on his deal with the shōgunate by giving Iemochi a deadline of May 10 for the expulsion of all foreigners from the country. With just two months to launch an attack that would, in all likelihood, have led to Japan’s demise, Iemochi was left scratching his head. Come the day of the deadline, he still hadn’t even contemplated action let alone taken any. And so with a roll of their eyes, this story’s second main protagonist(alongside Satsuma han) took the matter into their own hands and did what the shōgunate was too afraid to do: Chōshū han opened fire on foreign naval vessels.

The History of Chōshū han

Before we get into the details of Chōshū’s attack, let’s take a brief look at who they are and why they suddenly decided to make themselves a part of this epic tale. Comprising of the section of western Japan that is now known as Yamaguchi prefecture, Chōshū han was one of the larger hans in Edo Japan. However, prior to Sekigahara, the Mōri family, rulers of Chōshū, controlled a significantly larger area of land. Needless to say, Mōri had picked the wrong side in Sekigahara and had ended up having to hand the bulk of this land over to the Tokugawa shōgunate. For this reason, Chōshū han had, to some degree, always held a grudge against the shōgunate. When you consider the fact that both Satsuma and Chōshū were on the losing side of Sekigahara, Bakumatsu can actually be viewed as Sekigahara pt. 2!

Also similar to Satsuma, Chōshū amassed a small fortune in the mid-19th century. Their main port, Shimonoseki, was in an economically-strategic location, in that most ships in the west were forced to pass through it if they wished to travel to the northeast of Japan. Chōshū began selling supplies to these ships and charging them to store cargo in the port. In addition, being located on the west coast of Japan allowed Chōshū occasional contact with foreign ships, whose occupants provided them with the most up-to-date information on western medicine and military techniques. Ironically, though, despite their interest in western technology, Chōshū was overtly xenophobic. Yoshida Shōin, the most famous teacher in the region, had trained his students to embrace western weaponry and western military tactics for use against a foreign invasion. Now, his students were on the verge of facing the very invasion their teacher had prepared them for.

The Battle of Shimonoseki

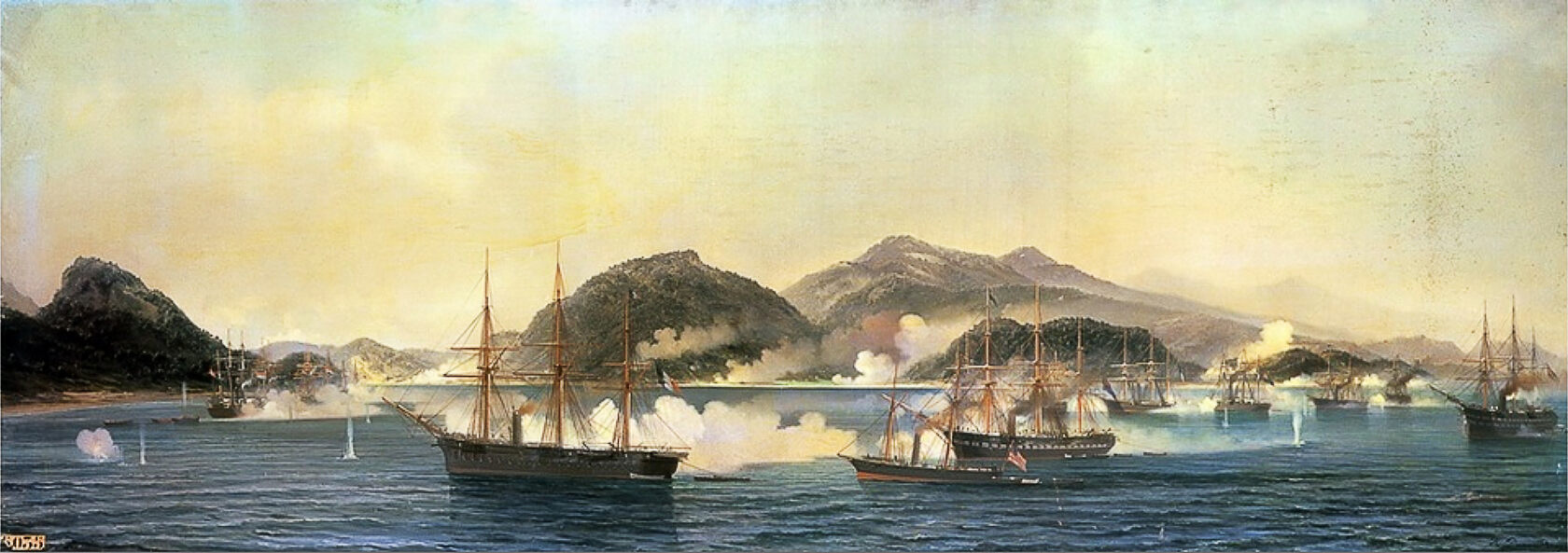

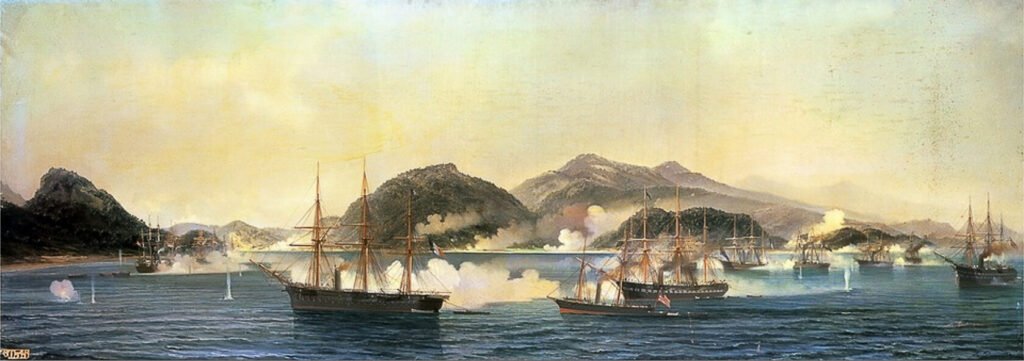

On May 10, Chōshū closed their ports to foreign ships and fired their canons at an American merchant vessel. Two weeks later they carried out similar attacks on British and Dutch vessels. One week after the final attack, however, Britain and France returned and destroyed three of Chōshū’s ships and most of their canons. No doubt when the shōgunate got word of this outcome, they felt like shaking their heads towards the west and screaming “we told you so!”

The Anglo-Satsuma War

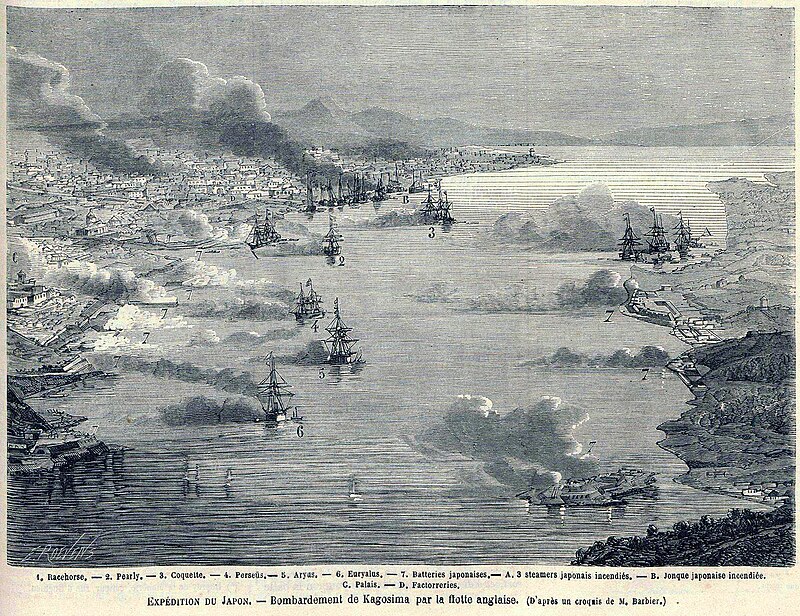

Chōshū having been dealt with, Britain turned its attention towards Satsuma. They still hadn’t received the money they were due from the Namamugi Incident, and the seven warships they led south suggested that they had no intention of leaving without it. Satsuma, however, was adamant that they would not be paying a single penny. This led to a short war which left three of Britain’s ships destroyed and one-tenth of the town surrounding Kagoshima Castle in ruins. Taking into account all deaths, injuries, and damages incurred, it’s safe to say that Britain were the victors. However, the war having cost them a greater amount of lives and ships than they could ever have expected, Britain was more than impressed with Satsuma’s military prowess.

Satsuma borrowed money from the shōgunate and paid Britain the full amount of compensation due for the Namamugi Incident. After that, the two become good friends. This granted Satsuma access to advanced ships and weaponry the likes of which not even the shōgunate was able to get their hands on.

The August 18 coup

While all this was going on, Chōshū, having shaken off their new foreign enemies, set about finding a new ally of their own: the court. Having been the only han in the country not to ignore the emperor’s will, noblemen within the court who had a strong affiliation with Chōshū suddenly found themselves in a position of power. Unfortunately, though, they got a bit carried away with this power and began sending out fake imperial decrees and letters in the emperor’s name. In order to put a stop to this, their political rivals were forced to find an ally strong enough to drive the Chōshū element of the court out of the capital. Who did they turn to? Satsuma, of course. Financially stable, popular with both the court and the shōgunate, and having taken on the might of Britain, Satsuma was top choice in the country for any han, group or organisation that needed a situation taken care of. In short, they were Japan’s hitman.

Even for Satsuma, though, the court was a huge ask. They couldn’t do it alone. And so they teamed up with Aizu han, governed by Matsudaira Katamori, who, if you’ll remember back to part one, had been put in charge of Kyōto. After getting the thumbs up from the emperor, on August 18, 1863, the two hans closed all gates to the palace and surrounded the walls with their soldiers, refusing entry to anyone from Chōshū. Meanwhile, inside the walls, seven top-ranking court officials with ties to Chōshū were banished from the capital.

Not all members of Chōshū left Kyōto, however; a small element remained, hidden in the capital’s dark corners, plotting revenge on behalf of their comrades back home, who scrawled derogatory comments regarding Satsuma and Aizu into the soles of their footwear so they could smear their enemies’ names into the dirt with every step they took.

The Ikedaya Incident

The previous year, Katamori established a police force consisting of low-level samurai who had made their way down to Kyōto from Edo. He named this force ‘Shinsengumi’ and tasked them with hunting down anyone plotting to harm the country’s new foreign guests and anyone suspected of targetting members of the court. In April of 1864, Shinsengumi stumbled upon a Chōshū-led plot to kill Katamori along with Tokugawa Yoshinobu before kidnapping the emperor and bringing him to Chōshū. Their investigation led them to an inn by the name of Ikedaya, where they found 20 or so of Chōshū’s rogue mercenaries. A battle ensued. It ended with every member of the Chōshū force either having fled, been taken captive or killed.

Chōshū divided

The battle at Ikedaya divided Chōshū into two parties: one furious party who insisted on marching the brunt of the han’s army to Kyōto to slaughter every last member of Satsuma and Aizu, and one terrified party who wanted nothing more than to plead to the court for forgiveness to put an end to the fighting and be allowed back into the capital. After much deliberation, the latter managed to convince the former to give their plan a try. So in July, Kusaka Genzui led a portion of the Chōshū army to Kyōto with a petition to hand to the court. Some court officials sympathised with Chōshū’s position, but ultimately, they were too few in number to rival the might of Satsuma and Aizu. Genzui’s petition was returned with a shake of the head.

The Hamaguri Gate Incident

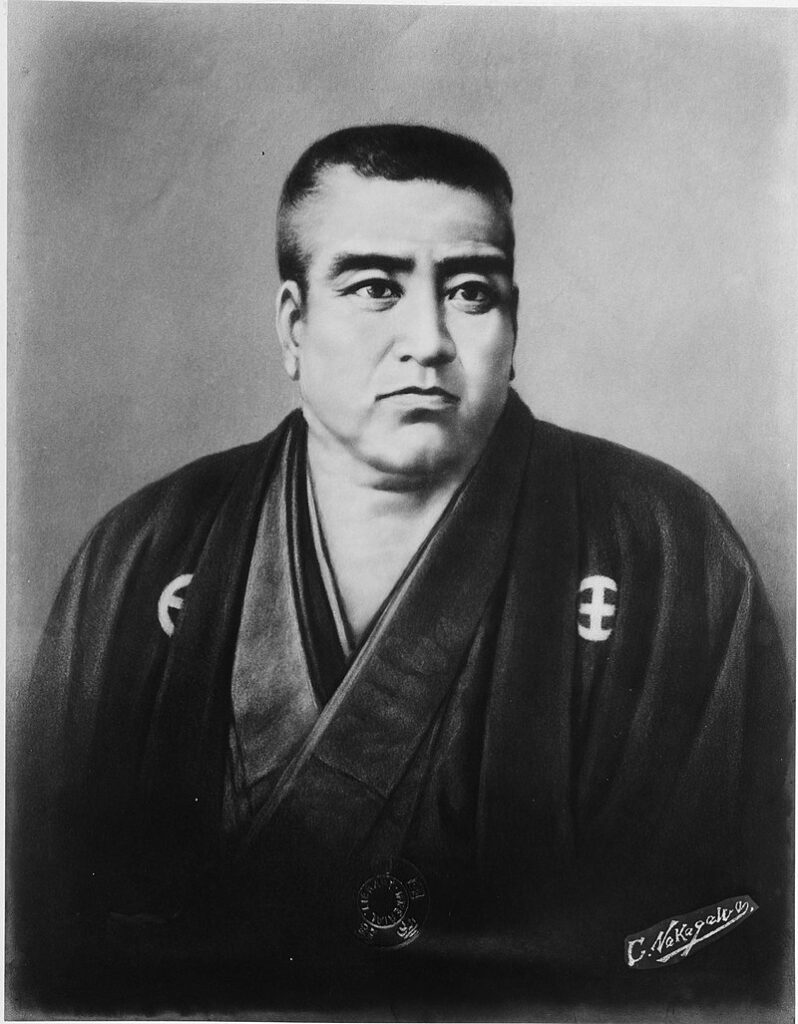

Naturally, the furious element of Chōshū’s army wasn’t about to give up and head home with their tails between their legs; contrary to Genzui’s orders, they split up into several teams and surrounded the capital, slowly advancing towards the palace, where they attacked Hamaguri gate, which was guarded by Aizu’s soldiers. Upon hearing of this development, Satsuma’s army charged toward the palace to assist its allies, led by Saigō Takamori―a man with a shaky past, but who, despite having a famously bad relationship with Shimazu Hisamitsu, was still arguably Satsuma’s top commander.

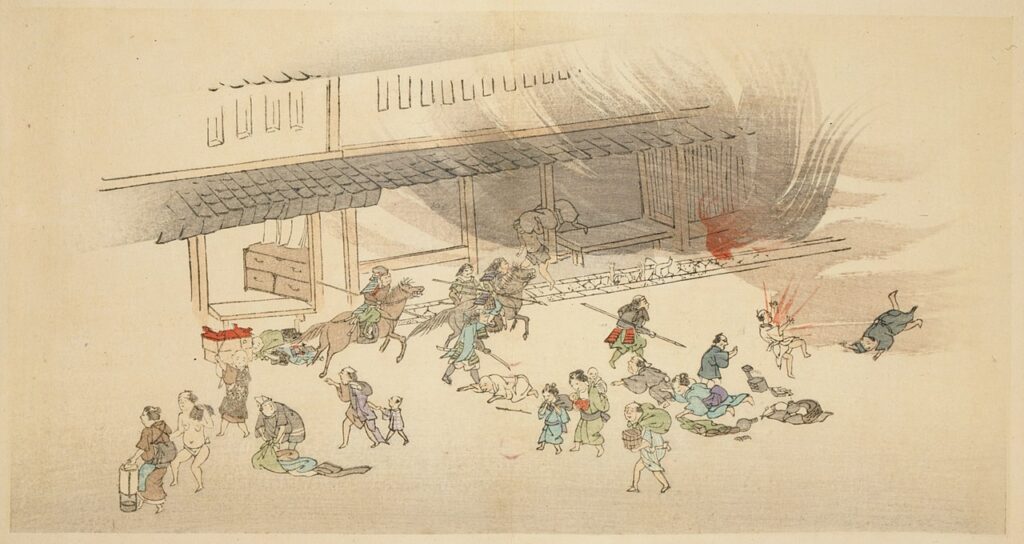

Bullets flew and, for the first time in history, penetrated the gates of the palace(the holes in Hamaguri Gate are still visible even today!). The Chōshū army was no match for the combined might of its enemies’ armies. Genzui made one last desperate attempt to plead his case to the kanpaku, whose dwellings were located within the palace walls. However, he found himself surrounded before he could carry out his final act of loyalty to his home, his lord and his teacher. Genzui took his life before it could be taken by his enemies. When the battle was done and the majority of Chōshū’s men had fled the capital, a fire broke out. To this day no one is sure as to its origin, but it continued to burn and spread for three whole days, destroying 28,000 houses―roughly half of all the hes in the city.

The Shimonoseki Campaign

As if Chōshū hadn’t taken enough punishment, before its defeated soldiers could even arrive home, Shimonoseki port found itself surrounded by 17 ships and 5,000 men belonging to the USA, Britain, France and Holland, who had all banded together in an effort to finally force the ostracised han to open its port to foreign vessels. With half of its army away and most of its canons destroyed, Chōshū was virtually defenceless. With no time to replace the canons they’d lost in the previous year’s battle, Chōshū’s men hastily began to construct dummy canons in the hope that they would be able to fool the enemy and buy enough time for the rest of their army to return. Their plan failed. The four-nation army destroyed the few remaining real canons, allowing them to dock and send their soldiers to fight on Chōshū soil. Needless to say, the battle ended in an undisputed victory for the foreign powers.

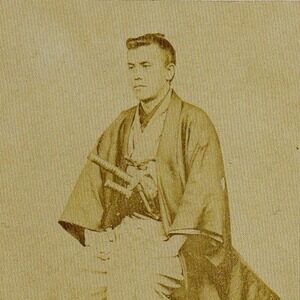

Takasugi Shinsaku was sent to negotiate the terms of Chōshū’s surrender. In the end, he agreed to let foreign vessels pass through Shimonoseki port and dock in times of adverse weather. In addition, he agreed that Chōshū would provide these vessels with all the water, food and supplies they needed. Finally, Chōshū promised not to repair the damaged canons and to pay the four nations a combined sum of $3,000,000. However, as Chōshū would never be able to pay off a debt that large, Shinsaku convinced them to have the shōgunate pay the money, explaining that the previous year’s attack on their vessels had been carried out on the shōgunate’s behalf.

The First Chōshū Expedition

As if that all wasn’t enough, the shōgunate decided they’d had enough and put together an army of 150,000 to annihilate Chōshū. Many acts were forgivable in the samurai community, but there were some things you just didn’t do, and putting bullet holes in the palace gate was one of them. The shōgunate’s mind was made up. No more Chōshū! Katamori’s older brother and head of Owari han, Tokugawa Yoshikatsu, was put in charge of the conquest, seconded by Saigō Takamori. Before setting off, Takamori paid a visit to a man by the name of Katsu Kaishū in order to get access to the shōgunate’s naval fleet. This meeting would turn out to be most fortuitous for Chōshū.

Katsu Kaishū

Katsu Kaishū was considerably accomplished within the shōgunate, having honed his skills at Nagasaki’s naval centre before being hand-picked to join a mission to the USA to finalise the trade agreement made with Townsend Harris in 1858. After returning from this mission, Kaishū opened his own naval training centre in Kōbe, where he taught his young students not only naval military techniques but also foreign military techniques and information regarding the ships and weaponry used by foreign fleets. The reason why Takamori’s decision to visit him was fortuitous for Chōshū is that during his time spend in the USA, Kaishū learned one unequivocal fact: Japan had no chance of defeating the foreign powers.

As such, since returning from his voyage, Kaishū had been conducting an Edo-era version of quiet quitting, where he carried out his job not for the sake of the shōgunate, but for the sake of future generations of Japanese soldiers who would have to fight under a new government. Kaishū knew the shōgunate was on its way out, which, in turn, meant that he would soon be out of a job. And so stoically, he did everything in his power to ensure that the transition went as smoothly and peacefully as possible. For this reason, I view Katsu Kaishū as the architect of Bakumatsu, guiding the protagonists towards the story’s inevitable end. And while Kaishū himself may not have designed this ending, he accepted it and set the other characters along its path. Had it not been for his actions, Bakumatsu could have been many times bloodier than it actually was.

Kiheitai

Kaishū explained to Takamori that the shōgunate was powerless and that Japan would need to form a new government if it was to have any hope of avoiding colonisation. He convinced him that Chōshū’s power and knowledge would be indispensable to this new government. Takamori returned to Yoshikatsu and relayed the information he had obtained from Kaishū. The two decided to negotiate with Chōshū rather than attack. In the end, it was decided that Chōshū would be forgiven on the condition that they swore loyalty to the shōgunate from that point forth and that the han’s top three officials, who were largely responsible for the attack on the palace, killed themselves. Chōshū agreed to these terms and all was right in the country once more… for a short time.

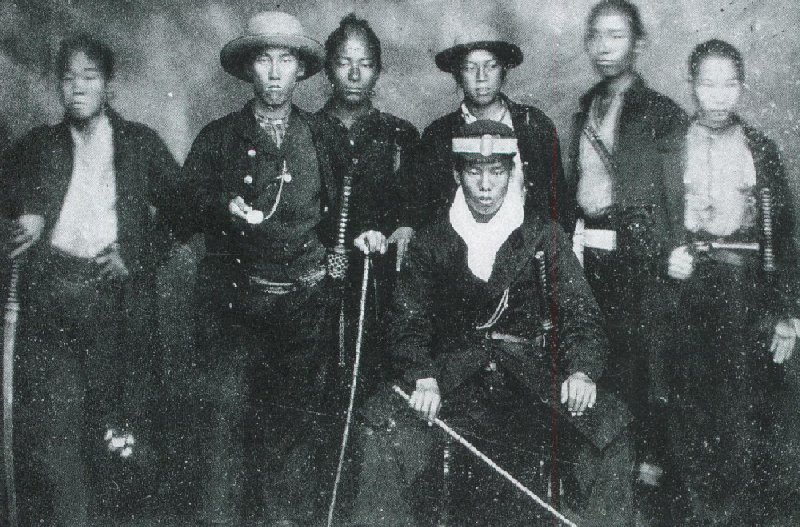

Soon after this peace treaty had been formed, Takasugi Shinsaku gathered 80 commandos and led a series of stealth attacks on a number of the han’s offices and storage facilities, stealing weapons, ammunition and even ships. His actions got the attention of others in Chōshū who were disgruntled with the result of the negotiation with the shōgunate. Before long, Shinsaku had amassed an army of 2,000 men. He named this band of renegades the ‘Kiheitai’. With the Kiheitai’s help, Shinsaku took control of Chōshū and continued to support the shōgunate on the surface while secretly plotting its downfall. Chōshū han was back!

Sakamoto Ryōma

Kaishū’s naval training centre shut down in 1865 under order of the shōgunate, mainly due to the fact that a number of its students were suspected of sympathising with Chōshū. Kaishū stepped down from his position of naval magistrate and sent his remaining students to Satsuma so that they could continue their training under the supervision of his associates in Kyūshū. Among them was a samurai from Tosa han by the name of Sakamoto Ryōma. Backed by Satsuma, Ryōma obtained a ship and began his own trading company. While travelling across Kyūshū, he noticed that more than a few people held the belief that the top hans in the country should band together to overthrow the shōgunate―in particular, Satsuma and Chōshū.

Putting Differences aside

Meanwhile, back in Chōshū, another young samurai(also, incidentally, from Tosa han) was harbouring similar ideas. When Nakaoka Shintarō crossed paths with Ryōma, the two decided to work together to bring to fruition the plan to overthrow the shōgunate. It wouldn’t be easy though; both Satsuma and Chōshū still held a great deal of hatred for one another. Nevertheless, it made sense for them to join forces; the shōgunate had banned foreign merchants from selling weapons to Chōshū. With no access to the advanced weaponry they would need to follow through with their plan of destroying the shōgunate, Chōshū would need to put their grudge aside and form an alliance with the han who had access to the most advanced weaponry making its way into the country: Satsuma.

Likewise, despite their ties with the shōgunate and the court, Satsuma’s position wasn’t as secure as it may have seemed: both the shōgunate and the court had begun to rely heavily on Matsudaira Katamori and Aizu han. Hisamitsu was well aware that once the shōgunate was done with Chōshū, it wouldn’t be long before they turned their sight south to Satsuma to take down the last remaining han powerful enough to start a rebellion. Satsuma would need an ally both willing and strong enough to help them take on their potential enemy when that time came.

The Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance

In order to convince both Satsuma and Chōshū of these facts, Ryōma bought 4,300 Minié rifles and 3,000 Geweer rifles in Satsuma’s name and delivered them to Chōshū. As Satsuma had been struggling with gathering enough food to feed its troops stationed in the capital, Ryōma next bought up large amounts of rice from Chōshū and delivered them to Satsuma. Both sides having been shown examples of what they can offer one another, Shintarō convinced Saigō Takamori to come to the negotiation table while Ryōma convinced Katsura Kogorō, the man who had assumed control of Takasugi Shinsaku’s new governing body.

In January of 1866, the two met in Kyōto and argued for days before Ryōma finally arrived and helped them come to agreement. This agreement―the Satsuma-Chōshū alliance―stated that if the shōgunate were to attack Chōshū, Satsuma would refuse to join the battle and do everything in their power to hinder the shōgunate’s efforts to advance west. In addition, Satsuma would make efforts to convince both the shōgunate and the court to pardon Chōshū. At this point, though, neither han was yet to make any formal agreement with regard to rebelling against the shōgunate.

Powerful secret alliances being formed, the shōgunate’s decline is starting to become apparent. Join me in the final part of this overview of Bakumatsu to find out how the shōgunate fares as the smaller powers around the country begin to band together and amass a new, greater power of their own.