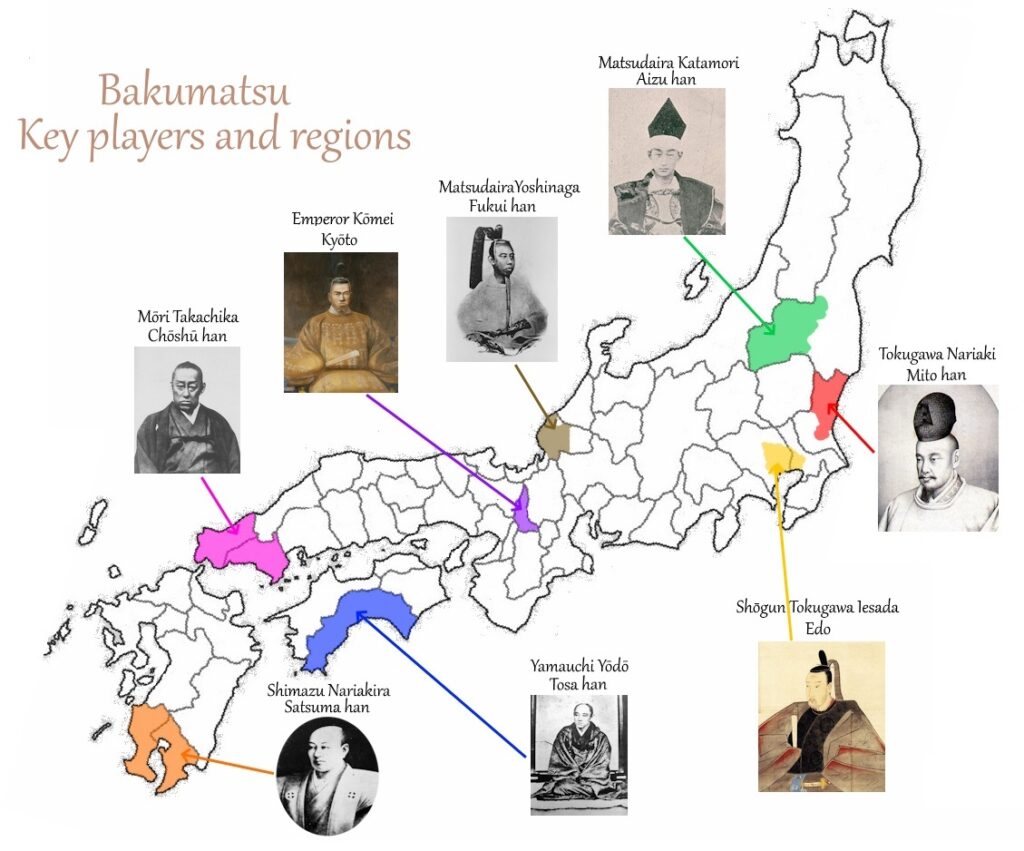

Bakumatsu – the end of the shōgunate Pt. 3

We reach the final part of our story. Bakumatsu is drawing to an end. Don’t be dismayed though; the final act proves to be far more shocking and bloody than anything we’ve seen so far. A power great enough to rival the shōgunate is beginning to form, and there may be little the shōgunate can do to stop it. Part three of our story begins where part two left off, with Satsuma and Chōshū having finally put their differences aside and realised that they have no choice but to rely on each other to ensure their mutual survival. At the moment, they are still playing defensively, hoping that the shōgunate leaves them alone and doesn’t force them to have to make use of the terms of their agreement. Let’s take a look at how this strategy played out.

The Second Chōshū Expedition

Unfortunately for Chōshū, regardless of their lack of interest in attacking the shōgunate, the shōgunate was gung-ho about attacking them. Having tried unsuccessfully to negotiate with their enemy for a year, the shōgunate made Chōshū a final offer: a 25% reduction of land and the retirement of their leader, Mōri Takachika, and his son, to end the hostilities once and for all. Chōshū refused, opting instead for a war they had virtually no chance of winning. One look at the numbers and that fact would be apparent to anyone. Shōgunate army: 105,000 Vs. Chōshū army: 3,500. That’s right… Chōshū chose to fight knowing full well they were outnumbered 30 to 1! Very few battles in Japanese history have ever been won with odds that bad.

Chōshū did have one thing going for them though: superior weaponry. Rifles provided the advantage of range. Up until the late Muromachi era, arrows had fulfilled that purpose. However, very few advancements had ever been made since their invention, and no one army was able to fire its arrows a more significant distance than those of its enemy. Rifles were a game changer; regardless of how heavily outnumbered you were, as long as your guns were capable of firing a distance further than that of your enemy, very few of the enemy’s soldiers were going to be willing to get close enough to attack you. Chōshū’s rifles, supplied courtesy of Satsuma, were superior to those of the shōgunate. This would prove to be a major factor in the outcome of the battle.

The shōgunate asked the majority of the hans in the west to join the battle, planning to attack Chōshū from four directions. However, it wasn’t until the battle drew near that they finally realised Satsuma wasn’t joining the party. In addition, the bulk of their troops consisted of small platoons from different hans mashed together into a kind of Frankenstein army. Not only were they not used to fighting together, but they had little idea of each other’s tactics and little time to figure them out. Perhaps even more important, though, was the fact that many of the soldiers felt the shōgunate was being too harsh on Chōshū. After all, the whole chain of events had started with Chōshū being the only region brave and loyal enough to carry out the court’s orders on behalf of the shōgunate. For this reason, when things started to get messy, many soldiers fled.

The deciding factor in the battle was the death of the shōgun. Tokugawa Iemochi died suddenly in July of 1866, leaving the shōgunate army little reason to continue fighting. After two months of warfare, the second Chōshū conquest was brought to an abrupt and anticlimactic end. One month later, Katsu Kaishū came to Miyajima, a small island off the southern coast of Chōshū han, to meet with Chōshū representatives and put an official end to the affair.

The Last Shōgun

The shōgunate picked Tokugawa Yoshinobu to fill the vacant shōgun seat. However, Yoshinobu refused, selecting to head the Tokugawa family but not the shōgunate. After months of pleading, the shōgunate finally managed to convince him to take the position in January of 1867. Unfortunately, though, one month prior to his acceptance, Emperor Kōmei died. Having been a key supporter of both Yoshinobu and Katamori, the emperor’s death was a major blow to the shōgunate’s influence over the court. Luckily for Yoshinobu, however, he had one other powerful supporter: France. Since Britain had been performing so well financially as a patron of Satsuma and Chōshū, their neighbours decided to get in on the action. Convenient as this was for the shōgunate, it did threaten to start an international war that could result in the colonisation of Japan. Satsuma, Chōshū, and Tosa all knew this. The time had come to seriously consider rebelling against the shōgunate.

The Satsuma-Tosa Alliance

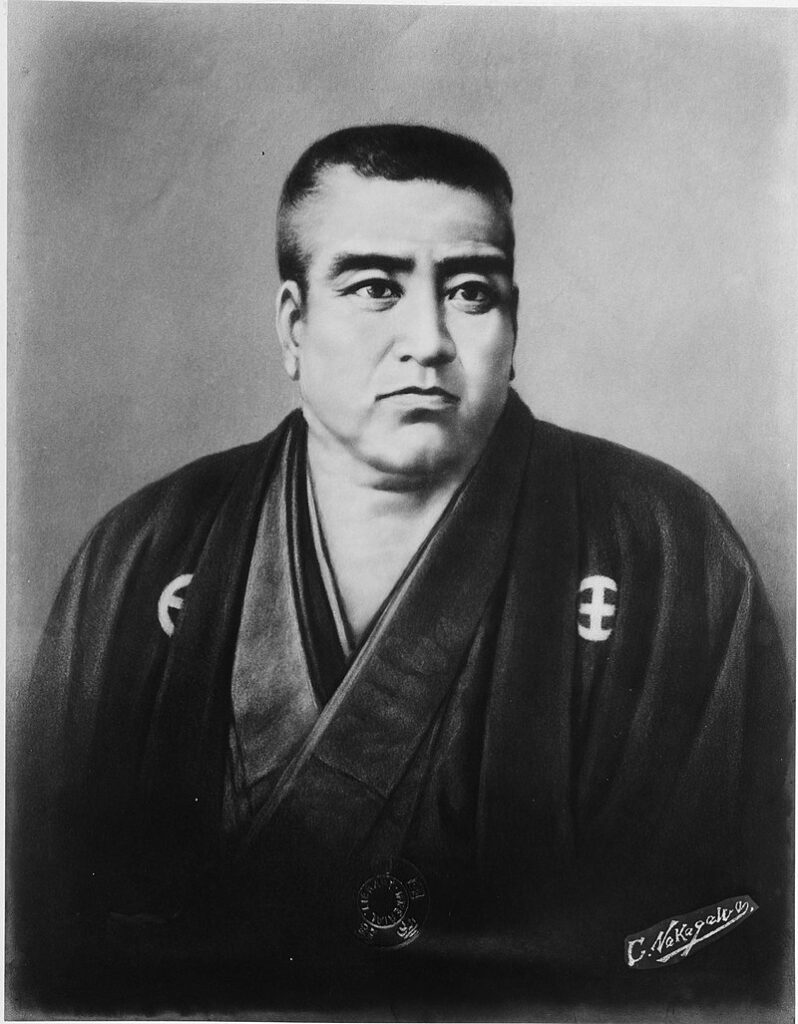

Sakamoto Ryōma got in touch with Gotō Shōjirō, a high-ranking official in Tosa han, and had him convince Yamauchi Yōdō to talk to Yoshinobu about abolishing the shōgunate and handing back control of the country to the emperor. In May, Tosa made an alliance with Satsuma aimed at toppling the shōgunate and unifying Japan. This, however, raised a new problem for the rebel side: Tosa, Satsuma and Chōshū were now on the same page with regard to their goal of getting rid of the shōgunate. However, they weren’t quite as united with regard to the method. Whereas many in their team desired to convince the shōgun, Yoshinobu, to abolish the shōgunate through friendly negotiation, there was another faction that were set on destroying the shōgunate through war. Their plan was to offer Yoshinobu conditions so harsh he could never agree to them, thereby awarding them the excuse they needed to launch their attack. Among this faction, there was one man in particular who felt it especially necessary to take down the shōgunate through battle: Saigō Takamori.

Edo Invasion

In October, Saigō began gathering rōnin from all corners of the country who shared his anti-shōgunate sentiment. He set them loose in Edo and had them commit acts of theft, arson and general violence against merchants and samurai who still supported the shōgunate. In response, Yoshinobu gathered together leaders of the hans who were still loyal to the shōgunate and had them police Edo. The anti-shōgunate forces were too strong, though; Saigō knew that with the right amount of pressure, he would be able to goad Yoshinobu into making the first move.

Relinquishment of Power

Meanwhile, Tosa han took the more peaceful approach of passing a petition to Yoshinobu, strongly advising him to abolish the shōgunate. After days of deliberation with his closest aides and top-ranking daimyō from around the country, however, he was still no closer to a decision. And then on October 14, something happened that changed the game: the court issued an imperial edict commanding Satsuma and Chōshū to take down the shōgunate by force. Due to the speed at which this edict was created and the clumsy wording that plagued its content, its authenticity came under question. However, authentic or not, Yoshinobu wasn’t willing to take the chance. This was the motivation he’d needed to tip the scale. Later that day, he relinquished control of the country, giving the emperor direct rule for the first time in over 500 years.

Yoshinobu wasn’t too traumatised by the decision, though; since the court had no experience whatsoever in dealing with the affairs of the country and had no ties to the foreign nations who were slowly pushing Japan further and further to open more ports and allow their citizens access to a greater area of the country, Yoshinobu knew the emperor would have no choice but to continue to rely on the shōgunate. Effectively, this meant that the shōgunate’s role in Japan would remain unchanged.

The Abolition of The Shōgunate

True to Yoshinobu’s premonition, the court did, indeed, find itself relying heavily on shōgunate members. Saigō and the others weren’t happy. This had been one of the reasons they’d wanted to destroy the shōgunate through battle rather than negotiation. However, since Yoshinobu had peacefully handed back the country to the emperor, it would be harder to find a reason to start that battle now. If physical force was no longer an option, they would need to rely on political force. On December 9, members of the court teamed up with officials from Satsuma, Tosa, Echizen, Owari, And Aki, and conducted a meeting in the presence of the emperor whereby they decided that the shōgunate would be dissolved and Yoshinobu would be made to retire and hand back half of his land to the emperor. The meeting hadn’t been set up purely to bully Yoshinobu, however; the role of kanpaku was also dissolved, assuring that no one man could have any significant degree of influence over the emperor from that point forth. As former emperor Kōmei’s son had only just assumed the role of emperor ten months prior and was just 15 years of age, it didn’t take much to convince him. The deal was done. Yoshinobu’s days in the command seat of Japan were numbered.

Attack on Satsuma’s Edo Manor

While all this was going on, the unrest in Edo had escalated to the point where the former shōgunate’s forces had surrounded Satsuma’s manor in Edo, which had naturally taken on the role of base of operations for the rogue rōnin. In late December, it all came to a head when the former shōgunate’s forces rushed the building and forced its occupants outside and into battle. The manor went up in flames and the rōnin scrambled to escape. Victory went to the former shōgunate. But while they had succeeded in forcing their enemy out of Edo, anti-Satsuma sentiment now took precedence among the samurai of Edo. Yoshinobu had a hard time quelling it. So, he decided to march an army to Kyōto and gain permission from the emperor to take down Satsuma. This way, he could deal with the rising discontent in Edo and, if given the thumbs up by the court, possibly even regain his position―two birds, one stone. Saigō must have been grinning ear to ear when he heard the news; the war on which he had been so dead set was about to kick off.

The Boshin War

The Battle of Toba-Fushimi

Named after the year of the Chinese calendar in which it began, the Boshin War broke out in January 1868, one month after the emperor fired Yoshinobu. The former shōgun led 15,000 disgruntled ex-employees to Kyōto. Satsuma and Chōshū were waiting for them by the outskirts of the city with 5,000 men of their own. The first battle of the long war ensued. Needless to say, outnumbered three to one, the allied army struggled to drive back the former shōgunate army at first. However, on the second day of battle, a messenger from the court arrived with a package containing a large number of imperial flags. Not having been brandished for several hundreds of years, these flags were utilised only in the most extreme of circumstances. They symbolised the fact that the army carrying them had the full support of the emperor. In all likelihood, the flags were knockoffs made at the last minute by members of the court who supported Satsuma and Chōshū. However, as no one on the battlefield had ever set eyes on the real thing, none were any the wiser. These flags were the equaliser the allied army needed to turn the tide of the battle. After all, who wanted to be branded an enemy of the emperor? Several hans retreated and fled the battle.

Yoshinobu’s escape

Rather than stay and fight to the last man, as you would expect of a shōgun(or even a former shōgun), Yoshinobu too fled the battlefield. He packed his things, got on a ship and sailed back to Edo, leaving those in his army who chose to stay and fight for him to die a bloody and meaningless death. Yoshinobu was criticised for this action, and, for a long time, history recorded him as a coward. However, recently, historians have begun to apply a different interpretation to the decision made by Yoshinobu that day.

Throughout the entirety of the Edo era, while every other han prioritised loyalty to the shōgunate over all else, Mito han’s loyalties lay with the emperor. Some theorise that this was a tactic set up by the shōgunate’s founder, Tokugawa Ieyasu, whereby if the shōgunate should ever fail, one branch of his family line would survive the turmoil and continue to flourish under the command of the court. If this was, indeed, his plan, it worked perfectly. As son of Mito han’s former leader, it’s entirely possible that Yoshinobu’s decision to flee the battlefield was based not on cowardice but rather loyalty to the emperor. Additionally, it’s equally possible that he chose to lose the battle and put an end to the division that had been created among the people of his country before foreign forces could take advantage of the divide and step in to claim Japan for themselves. Whatever the reason, there’s no denying that Yoshinobu’s decision was of benefit to Japan.

The Surrender of Edo Castle

Once in Edo, the former shōgun put himself under house arrest in Kaneiji, one of the Tokugawa family’s two official temples, as a sign that he no longer intended to continue opposing the new government that had been formed by Satsuma, Chōshū, and Tosa. Katsu Kaishū was left in charge of Edo Castle. By April, word had reached Edo of the advancing government army. Kaishū knew that its commander, Saigō Takamori, was set on burning Edo to the ground in an effort to destroy the last of the former shōgunate army and prove to both the people of Japan and the foreign forces that the new government was the country’s one true ruling force. Kaishū sent a messenger to Takamori, inviting him to the castle to discuss the terms of a surrender.

In all likelihood, Kaishū had predicted long ago that this day would come. He had known for years that the shōgunate’s days were numbered, and he had even, to some degree, orchestrated its downfall. He had no qualms about handing over everything the shōgunate owned to the new government. His only concern was the safety of Yoshinobu. And so after a short couple of days of discussion, Takamori agreed to have his army stand down and to allow Yoshinobu to go under house arrest in his home territory of Mito in exchange for the handover of Edo Castle, all the shōgunate’s ships and weapons and the promise that Kaishū would get the last of the former shōgunate army under control. Six-year-old Tokugawa Iesato, a fifth-generation descendent of the 8th shōgun, Tokugawa Yoshimune, was given permission to head the Tokugawa household and awarded 70,000 koku worth of land in Shizuoka.

The Battle of Aizu

With their commander having surrendered and made his way to Mito, the war should have been over. A handful of soldiers weren’t willing to give up the battle just yet, though. 4,000 of them moved into Kaneiji(despite the fact their leader had already left) and made it their new stronghold. The new government’s army led 10,000 men and a number of Armstrong canons to that stronghold and drove them out within a day. The war was far from over. As the former shōgunate army still seemed keen to fight, Saigō et al. set their sights on Aizu―the han chiefly responsible for their five-year headache. 31 hans in the north of Japan formed an alliance with Aizu and decided to fight both alongside them and on their own turf. The government army spread out to take on as many of these small local armies as they could while advancing the bulk of their men on Aizu.

More and more soldiers poured into Wakamatsu Castle―Aizu’s main stronghold―and forced a siege. The invading army took down Aizu’s support castles one by one until they reached Wakamatsu. The former shōgunate army lasted a month before finally surrendering in September. As leader of Aizu, Matsudaira Katamori was put under house arrest in Edo(or Tōkyō, as it had been renamed by the government army). The remaining residents of Aizu who had managed to survive the war were later relocated to an area known as Tonami in the far north of the country.

The Battle of Hakodate

The north may have been subdued, but the shōgunate still had one trick left up its sleeve: Enomoto Takeaki―a naval officer who had studied western military tactics in the Netherlands. While the new government was busy dealing with Aizu and the rebels in the north, Takeaki got his hands on eight ships docked in Tōkyō which, until shortly before, had been the property of the shōgunate. With security still scarce, he gathered 2,500 men and snuck them on board the ships before setting sail and heading north, stopping at numerous ports to pick up war survivors. Among these survivors was Hijikata Toshizō―Shinsengumi’s deputy commander.

Shinsengumi hadn’t fared well in the war; many of their top members had either left the group or died in battle, and their leader, Kondō Isami, had been caught and beheaded shortly before the war on Aizu began. Convinced that the mainland had been lost, Toshizō joined Takeaki’s crew and sailed far north with him to Ezo, the large island to the very north of Japan currently known as Hokkaidō. After driving off all the government’s forces to the south of the island, Takeaki declared his new territory an independent country―the Republic of Ezo―and set about making it a safe haven for all former members of the shōgunate. His dream didn’t last long, though; the government’s forces made it to Ezo in April of the following year with the aim of finishing off the shōgunate once and for all. Less than a month later, Toshizō fell in battle and Takeaki was taken captive. This marked the end of the Boshin War.

The Meiji Restoration

With their final enemy defeated, the fledgling government set to work ushering in a new era of peace. They named this era ‘Meiji’. As most of Kyōto had burned down during the course of the previous ten years, they moved the capital to Tōkyō. At first, the government consisted primarily of members of Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa, Hizen(who had supplied Saigō’s army with advanced weaponry during the Boshin war) and former members of the court. Enomoto Takeaki was released in 1872 and invited to join the government. As for what happened next, check out my article on the Meiji era if you’re interested in finding out. And as for what happened to Sakamoto Ryōma and Nakaoka Shintarō… that’s a story for yet another article, which I’ll definitely be writing one day.

Conclusion

Thus concludes this abstract of Bakumatsu. Thank you for staying with me to the very end. As a small reward, there’s a map below containing the location of most of the major battles that occurred during this epic period of Japanese history. I say ‘most’ because it would be impossible to give a full account of what happened during the short 15-year period even with three fairly sizeable articles. I’ve had to skip over many interesting people, battles and events in order to(hopefully) have given you a good idea of the main story. I did, however, add a number of explanations and theories that I wish I’d known when I first started studying the period. If I haven’t fully satisfied your thirst for Bakumatsu knowledge, however, take a look at some of my other articles detailing the parts I missed out.