Japanese history overview Pt. 10: The Meiji era

We’ve made it to the modern world! The age of the samurai is over. Japan has entered the Meiji era. No longer is it a closed-off, self-sufficient island that wants nothing to do with the outside world; it is now a fledgling nation ready to embrace the Western world and all its ideals. Slowly but surely, over the course of the Edo era, Dutch texts seeped into the country and taught the people of Japan of a life that could be lived outside of samurai rule. They learned of advances in medicine, technology and political structure―advances the shōgunate refused to embrace. The desire to participate in the outside world grew to the point where the general populace began to realize that feudalism was an outdated societal system. They longed to experience a wider, more open world. And so with the help of some of the top-ranking hans in the country, they overthrew the shōgunate and returned the right to rule the country to the emperor.

The Meiji government

Meiji era: 1868 – 1912

The main protagonists in the chain of events that led to the establishment of the Meiji government were Satsuma han, Chōshū han, Tosa han and, to some extent, Hizen han(they showed up at the last minute and supplied the others with advanced weaponry). So, needless to say, the newly-formed government that emerged from the ashes of the war that paved the way for this new world consisted mainly of members from these four regions, as well as a handful of members of the court who had helped them get the emperor on board with their plan.

Important figures in the Meiji government

Name | Domain |

Etō Shinpei | Hizen han |

Gotō Shōjirō | Tosa han |

Itagaki Taisuke | Tosa han |

Itō Hirobumi | Chōshū han |

Iwakura Tomomi | Court noble |

Kido Tadayoshi | Chōshū han |

Kuroda Kiyotaka | Satsuma han |

Ōkubo Toshimichi | Satsuma han |

Ōkuma Shigenobu | Hizen han |

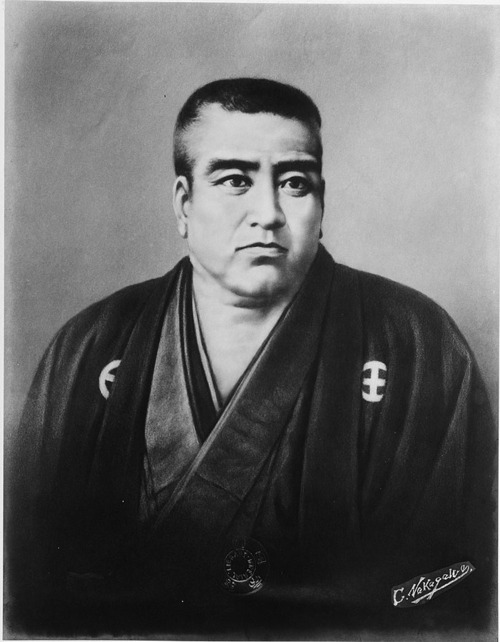

Saigō Takamori | Satsuma han |

Sanjō Sanetomi | Court noble |

Yamagata Aritomo | Chōshū han |

Japan was still far from a democratic system of rule, however. In its early days, the Meiji government was simply a more liberal version of the shōgunate; it gave people the right to roam the country freely and pursue any career path they wished, but it didn’t give them a say in the political decisions that affected their lives.

The Meiji Restoration

The first of these decisions was the return of all land and people to the emperor. Unlike the Edo era, where the shōgunate recognized the right of the daimyō to rule over designated domains, all land was now under the direct control of the emperor. As such, he had the final say as to who was put in charge of each region and how they should govern those regions. During the Edo era, daimyō had direct control over the people living on their land, and, therefore, were free to impose taxes in the form of rice and labour any time and in any manner they wished. Similarly, in the Meiji era, all people belonged to the emperor, who was free to decide how much and in what manner they should be taxed.

The Iwakura Mission

Obviously, the emperor didn’t actually make any of these decisions himself; he relied on the government, which used him as a figurehead to give the people someone more pleasing to look up to than a bunch of former samurai(effectively terrorists), who intended to use their position for personal gain. Given that few of these figures had any idea how to govern a country, Iwakura, Ōkubo, Itō and Kido embarked on a fourteen-month trip that led them across 12 countries in Europe and North America in order to get a better grasp of economics, infrastructure, engineering, finance, education, architecture… basically government 101.

Before they left, they gave the others strict instructions not to make any major changes while they were gone. But like a teenager who’s been left alone in the house while his parents go on vacation, the minute the ships left the port, Saigō, Sanjō and the others started planning a house party. They reformed the postal, monetary, education and railways systems, enforced conscription on the people in order to get a head start on an army, imposed a 3% land tax, abolished the class system that had been the lynchpin of the Edo era and switched to the Gregorian calendar. Mummy and Daddy would NOT be happy when they returned!

Introduction of prefectures

Bigger than any of these reforms, however, was their decision to replace hans with prefectures. Currently, Japan consists of 47 prefectures. In 1871, it consisted of a whopping 305! It took the government a while to find a workable balance between the number of prefectures and their respective sizes; too many meant they would be a nightmare to control whereas too few meant that each prefecture was potentially large enough to start a rebellion one day. Finally, in 1888, they arrived at the Goldilocks figure of 47, which included Hokkaidō and Okinawa―two regions Japan had been aiming to add to its collection for a long time.

Unlike the Edo era, where each han was governed by a designated daimyō family, it was decided that these new prefectures would be controlled by governors known as kenrei, hand-picked by the Meiji government. This was a huge decision that required long deliberation. After all, what former samurai family was going to want to step down from a position their ancestors had held for hundreds of years? The government arranged an army consisting of soldiers from each member’s home region to quell the expected uprising. However, perhaps due to the fact that they had led by example and had the former leaders of their own domains quietly relinquish their positions, or perhaps due to the fact that in the previous few years they had successfully asserted their dominance over the people, very few kicked up a fuss.

Funnily, the education reform and conscription system turned out to be more controversial; as the majority of the general populace were still impoverished farmers, having their children forced to leave the farm to go to school or join the army was a huge blow to their livelihoods. In many cases, the reduction in farmhands meant almost certain starvation. Numerous riots broke out around the country in response to the announcements of these changes.

Foreign powers

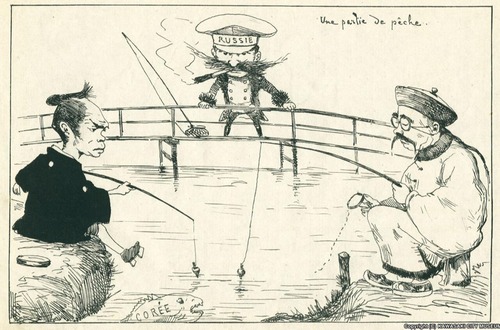

Since Japan had now ventured out into the jungle that was the Western world, it needed to be cautious of any predators that may be lurking, lying in wait for new, fresh prey that wasn’t prepared to escape their clutches. USA and Britain seemed friendly enough. Holland too didn’t pose an immediate threat. Russia on the other hand… The fact that it was constantly looking for excuses to expand its territory south rang alarm bells for Japan. Russia justified its actions as needing to secure a port that wouldn’t freeze over in the winter, but Japan wasn’t buying it.

Joseon

The biggest problem was the fact that Russia was inching closer and closer to Joseon―the empire under which the Korean peninsula was ruled at the time. If Joseon fell, Japan was next. So, the Meiji government sent envoys to try to convince Joseon of the threat posed by its large and powerful neighbour. However, while towards the end of the Edo era Japan had spent decades swatting away the numerous foreign flies relentlessly buzzing around its ports, it now found itself in the position of the fly. Joseon still considered itself a part of Qing. Salty over the fact that Japan had its opened gates to the Western world, Joseon refused to have anything to do with the Japanese envoys. In fact, the situation escalated to the point where the Joseon court decided to kill anyone in the country found dealing with Japan.

The division of the government

This didn’t faze Saigō. As commander of the Satsuma/Chōshū army during the Boshin War, he had faced far worse threats. He suggested that he personally make his way to Joseon to negotiate the situation. This split the government into two groups: those who supported Saigō’s decision and those who thought he was out of his mind. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the former consisted mainly of the members of the government who had remained behind and taken the reigns while Iwakura and the others were backpacking across Europe. In the latter’s defence, they had spent over a year abroad. They’d seen whole other worlds that Saigō and his band could barely dream of. They weren’t interested in Joseon; they only wanted to set Japan on a track that would allow it to catch up with the advancements they’d witnessed as quickly as possible.

After months of arguing, those in favour of ignoring the Joseon situation emerged victorious. Unsatisfied with the result, Saigō, Itagaki, Etō, Gotō and around 600 or so other government and army officials all resigned. Itagaki and Gotō returned to Tosa and established a political party to rival the government, which, by now, Ōkubo had assumed full control of. Saigō returned to Satsuma to become a teacher of military arts.

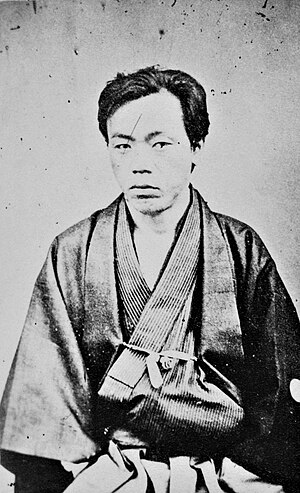

The Saga Rebellion

When Etō Shinpei returned home to Saga, he found himself facing a very similar situation to the one he’d just left; his home prefecture was split into two groups of its own: one in favour of attacking Joseon and forcing it to open its gates to Japanese envoys, and one opposed to the Westernisation of Japan. Around the time the government started squabbling amongst itself, these two groups put aside their differences and banded together into a super group with one express purpose: force the government to enforce their ideals. As a symbol of Saga, Etō was talked into taking partial control of this rebel group. Not long into the rebellion, though, the government’s army reached Saga and quickly took down the enemy forces. Etō was hunted down and tried in court. The trial was a farce, however; the government simply wanted permission from the people to execute Shinpei. Two days in, he was sentenced to death.

By 1875, the situation between Japan and Joseon hadn’t improved much. Joseon opened fire on Japanese ships, leading to a small skirmish between the two countries. Not all in Joseon were opposed to Japan, though; a pro-Japan faction existed, who fought to have Japan accepted into the country and provide it with the military knowledge and weapons it needed to strengthen itself against the looming foreign threat. In the end, Qing stepped in and forced Joseon to sign a treaty with Japan, ensuring peace for the foreseeable future.

The end of the samurai

In March of 1876, the former samurai were forced to return their swords. In August, they had their allowances revoked. Since the start of the Meiji era, the government had been paying a stipend to all former members of the samurai class. Needless to say, this put a massive strain on their budget, the likes of which they couldn’t have… no… should have been able to predict. By 1876, this cost now accounted for 30% of the government’s national expenditure! So they took the allowances away and replaced them with government bonds and an apologetic bow. There were mass riots; especially among Kyūshū. Rebellions broke out in Kumamoto, Fukuoka, and Yamaguchi. Once the government was finished putting them down, it turned its sights to Kagoshima. Saigō’s followers had increased, and, given the tide, certain members of the government were becoming paranoid that the wave of discontent would work its way to the very south of Kyūshū. As a measure against another possible rebellion, they decided to confiscate all of Kagoshima’s gunpowder and send 20 police officers down south to survey the situation.

The Seinan War

And so began the self-fulfilling prophecy: Saigō’s followers became increasingly suspicious until they were fully convinced that the government was planning to wage war with them. Saigō did his best to calm his students down but eventually realised that they were set on carrying out a pre-emptive strike with or without his support. Perhaps he was feeling nostalgic for the age of the samurai, or perhaps he secretly longed to die in battle. Whatever the case, Saigō decided to take charge of his budding army and lead it north. Unlike the rebellions that had occurred the previous year, this one took longer than a month to quell. The Kagoshima army took on the might of the government’s men for a full eight months before finally succumbing. The battle having been lost, Saigō found a private area away from the fighting in which he could end his life in a style fitting of a samurai.

Ōkubo’s assassination

Having been friends since childhood, Ōkubo Toshimichi lamented Saigō’s death. He didn’t have long to grieve, though, as he was assassinated the following year while on his way to meet with the emperor. A group of disgruntled former samurai blocked off his horse-driven carriage and thrust swords through the windows until the country’s leader was dead. Their mission complete, they handed themselves in to the police and explained their reasons: they were angry about the amount of money the government had been wasting on unnecessary construction projects, the ostracization of former samurai and the rebellions that had resulted from it, and Ōkubo’s failure to renegotiate the one-sided treaties Japan had signed with foreign nations twenty years ago.

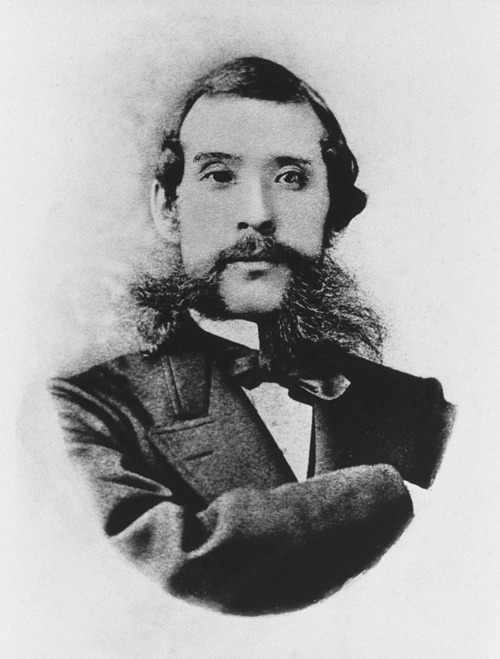

With the majority of the Meiji government’s original members either dead, retired or disgraced, chance fell to Itō Hirobumi, a former member of Chōshū han, who, in his early days, had participated in some acts of terrorism on foreign embassies. On the other hand, he had also spent a good deal of time studying abroad and, therefore, had relatively good English skills compared to the other members of the government. Given that Japan expected to be dealing with foreign dignitaries in the near future, this stood Itō in good stead. Shortly into the job, however, he began to realise just how difficult a position head of the government was.

The Freedom and People’s Rights Movement

Since leaving Tōkyō, Itagaki Taisuke and Gotō Shōjirō had been busy establishing a movement aimed towards transforming Japan into a democratic society. They started a political party, Aikokukotō, and Risshisha, a social group dedicated to increasing awareness of Japan’s need for democracy. In 1881, Itagaki established a new party named Jiyūtō(the Liberal Party) and began to put pressure on the government to form a democratically-elected parliament. At the same time, Ōkuma Shigenobu started the Constitutional Reform Party. Various groups from both parties gathered in Osaka and collected a petition of 87,000 names from people who agreed with their ideals. Itō could no longer rule unopposed; the pressure from the people was too overwhelming. And so, he agreed to both establish an assembly and create a constitution within the following ten years.

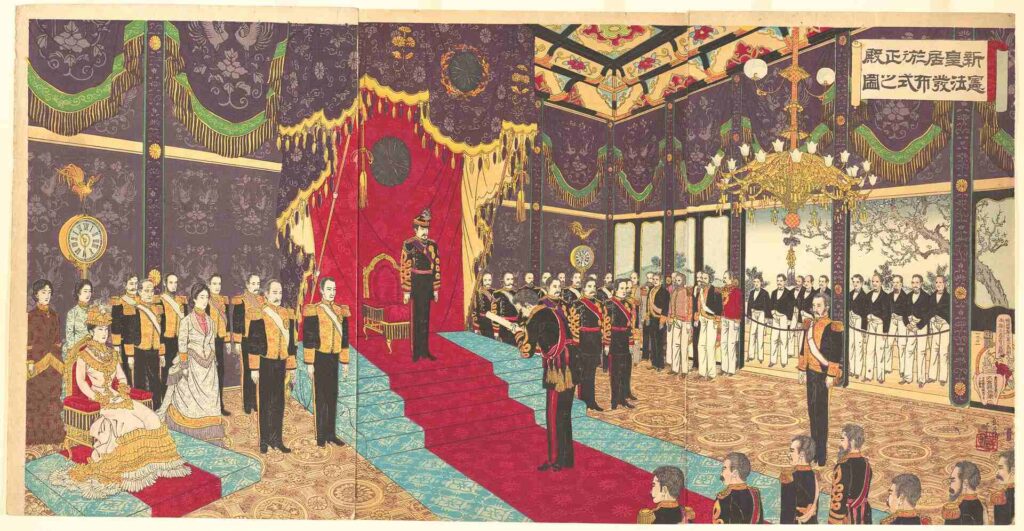

Constitution of the Empire of Japan

In 1885, Itō formed Japan’s first cabinet and declared himself prime minister. In 1889, Japan’s constitution was announced in the presence of the emperor. The ‘Constitution of the Empire of Japan’ was based on the German constitution. It centred around the Imperial Family and put emphasis on the emperor as ruler of the country, giving him undisputed control over the government, army and foreign affairs. One year later, the Imperial Diet assembled for the first time. It was made up of two houses: the House of Representatives and the House of Lords. The latter consisted of members of the former aristocracy and descendants of samurai families. The former consisted of elected officials. Any man over the age of 25 with an annual tax return exceeding 15 yen($2000 in modern money) was eligible for election.

The First Sino-Japanese War

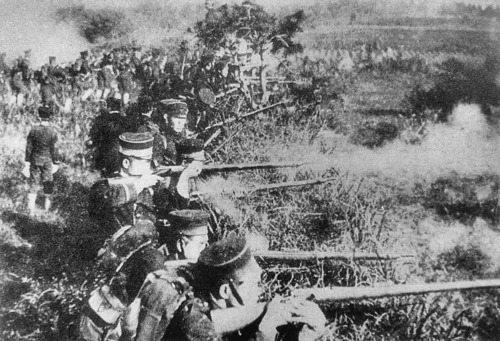

With the government formed and a democratic(albeit severely exclusive) assembly established, Itagaki’s democratic army calmed down. Politically, all was well in the country. Tensions between Japan and Joseon, however, persisted. In 1894, a religious group by the name of Donghak began a rebellion in Joseon. The country had suffered terrible droughts for the past couple of years, and rather than take action to aid the starving farmers that made up the bulk of the populace, the Joseon court raised taxes and formed trade agreements with Qing and Japan which agreed to extortionately high tariffs on Joseon’s side. As support for Donghak grew, the court became too weak to handle them alone. And so they called for the assistance of Qing and Japan. Both countries sent their armies over to take care of the situation.

Naturally, Donghak was no match for the might of the two powerhouses. But once they had been dealt with, Joseon faced a new problem: like the old woman who swallowed a spider to catch the fly, Joseon was unable to rid itself of the spider. Neither Qing nor Japan was willing to leave first. Qing wanted to retain control of Joseon while Japan wanted Joseon to become independent and embrace the Western world so it could better protect itself from Russia. Japan compromised, proposing that the two nations work together to help Joseon form a new government―one properly equipped to deal with the looming threat. Qing refused. Both sides’ armies remained, staring each other down until July, when Qing opened fire on Japanese ships that were heading for Joseon. This was the start of the Sino-Japanese War.

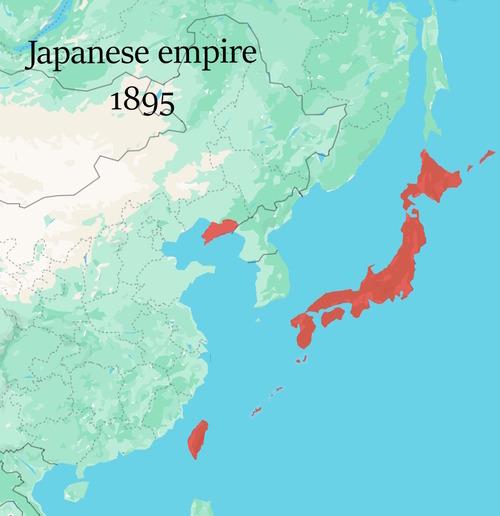

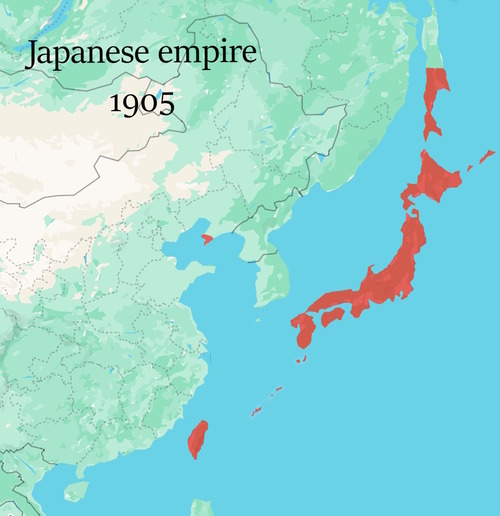

Leaving the details of the war to a more dedicated article, let’s skip to the result. in April 1895, Qing surrendered to Japan and sent representatives to meet with Itō Hirobumi and a number of other Japanese officials in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi prefecture. The terms of Qing’s surrender were negotiated and a treaty was formed. Qing acknowledged Joseon’s independence and handed over Taiwan and the Liadong peninsula in addition to monetary compensation to the value of 200,000,000 ryō(around $2,300,000,000 in modern money).

Despite the overwhelming difference in the sizes of the two nations’ armies, Japan was able to defeat the sleeping dragon chiefly due to the fact that it had superior weaponry supplied by Western countries. Qing, not yet having embraced Westernisation, was stuck with outdated rifles which had low firing rates and short ranges. In addition, having lost multiple wars to Britain and France in the previous few decades, motivation to fight on the part of the soldiers was almost non-existent.

Growing tensions towards Russia

Shortly after Japan took control of its new territories and expanded its little empire into eastern Asia, Russia came knocking on its door with France and Germany as backup, demanding that Japan return the Liadong peninsula to Qing and citing that if Japan were to maintain control of the territory, it could cause unrest in Asia. Victory over Qing had awarded Japan a newfound confidence, but it wasn’t so cocky as to believe it could take on the combined might of three Western nations. Reluctantly, the government returned the peninsula. No sooner had they returned it, though, than Russia swooped in and pressured Qing into leasing it to them! The animosity Japan had held towards Russia for close to three decades grew significantly from that point on.

Once word got out that Qing was renting out its land, other countries swooped in, scooping up huge chunks of territory. England, France and Germany started a competition to see who could lease the most of the massive country. Russia too obtained the right to build its Siberian Express railway through Manchuria to the east of Qing. The entire country was turning into one big international theme park. Needless to say, few of Qing’s citizens were happy with this development. A secret society known as the Boxer Movement took it upon itself to rid the country of foreigners. The USA, Britain, Japan, Russia, France, Germany, Italy and Austria all sent soldiers to take them down. The battle commenced. Once the movement was taken care of, Russia stationed troops in Manchuria under the pretext of needing to protect the railway and the civilians they had living in the area. Japan, USA and Britain opposed this action. Russia agreed to remove its troops once the area was secure.

Britain remained suspicious. However, as it was busy fighting a war in South Africa, it didn’t have the manpower to deal with Russia at that time. So, in 1902, Britain formed an alliance with Japan, leaving Russia under its careful watch. This alliance stated that if one party were to find itself in a war with two other countries, the second party would step in and even the odds. This effectively prevented Russia from being able to rely on Qing should it end up in a war with Japan. With little other choice, the Russian government agreed to withdraw their troops slowly in three parts. However, they missed the final deadline. Even still, Japan wasn’t yet prepared to go to war. Instead, the government opted for negotiation, proposing that they would acknowledge Russia’s interest in Manchuria if, in return, Russia agreed to acknowledge Japan’s interest in Korea(as Joseon was now known). Russia refused.

And so Japan resorted to giving Russia a visual demonstration of how its actions appeared to the outside world: the government dispatched troops to Korea and began to provide the fledgling nation’s government with military advice. At first, Russia wasn’t fazed by this; it agreed to allow it on the provision that Japan didn’t advance any further north than Pyongyang―currently the capital of North Korea. This would allow Russia to retain some control over the Japan Sea. In addition, once the Siberian Railway was complete, it would be able to smoothly send reinforcements to Korea should a war break out. Ironically, it was this need to prepare for war that motivated Japan to make the first move.

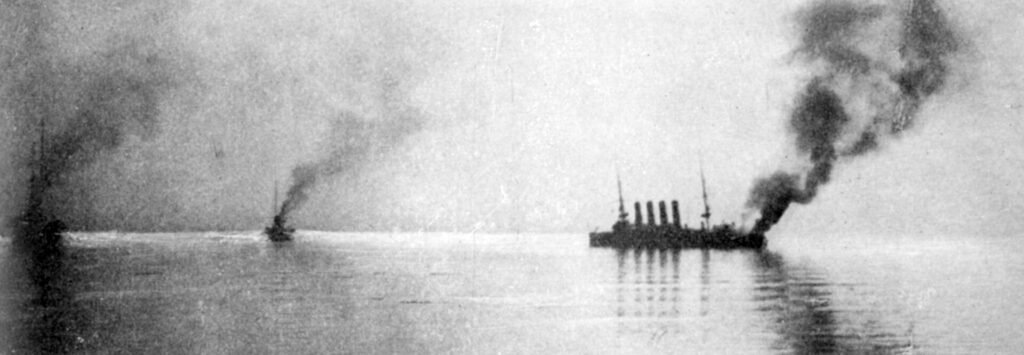

The Russo-Japanese war

Come February of 1904, Japan formally ended diplomatic relations with Russia and began to advance troops north of Pyongyang. The Russo-Japanese War had begun. It raged on for a year, various battles occurring both on land and at sea. For the most part, Russia was simply buying time while it sent a portion of its infamous Baltic Fleet to Asia to finish Japan off. However, when the fleet arrived in May 1905, it found the Japanese navy lying in wait, led by legendary naval commander Tōgō Heihachirō. Counter to what Russia had expected, the battle ended with 21 of the Baltic Fleet’s 38 ships at the bottom of the ocean and six more taken captive. Shocked as it was at the result, Russia still had the option to send more of the fleet over and try again. However, as luck would have it for Japan, the Bloody Sunday massacre had occurred just four months earlier. With a possible revolution on the cards, Russia couldn’t waste any more time swatting away flies. Reluctantly, the Russian government surrendered.

Representatives of each country met in Portsmouth, USA, to discuss the terms of Russia’s surrender. In the end, Russia agreed to acknowledge Japan as Korea’s guardian and handed over half of the large island to the north of Hokkaidō known as Sakhalin in addition to the lease rights to Lüshun port. However, no matter how many times they were prompted by both Japan and the USA, the Russian government refused to pay any form of monetary compensation. The war had taken the lives of almost 100,000 Japanese soldiers and virtually bankrupted the country. With nothing to show for this sacrifice other than a relatively useless little patch of land to the north and a couple of lease rights in Qing, the people were furious. Protests were held and riots broke out in Tōkyō.

The Annexation of Korea

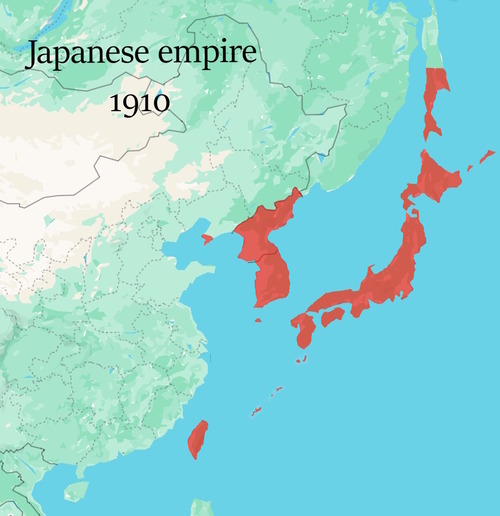

After the dust had settled, Britain agreed that it would be best for Korea if it remained under the supervision of Japan. It was, after all, a fledgling country with no real experience of having governed itself, having remained subordinate to a number of Chinese dynasties for hundreds of years. The USA too agreed to acknowledge Japan’s right to Korea if Japan, in return, acknowledged its right to the Philippines. With two leading nations backing them up, the Japanese government took over Korea’s diplomatic rights, forbidding the Korean government from signing a treaty with another country without Japan’s authorisation. Furthermore, they named Itō Hirobumi Resident General to Korea and constructed an office in the capital from where he could take charge of the nation’s army.

It goes without saying that Korea was beginning to become more than a little concerned with Japan’s overbearing presence. So, in 1907, the Korean government sent secret messengers to the International Peace Conference in Hague to make Europe aware of the situation. However, the international community was already fully aware of Japan’s interest in Korea, and few countries had anything to gain by opposing the situation. Given the fact Korea hadn’t been invited to the conference to begin with, representatives of the attending nations needed little excuse to turn the messengers away. And so Korea switched to Plan B: if world leaders weren’t going to help them, they’d get media support. The messengers spread their story around numerous top newspapers in Europe in the hope that they could gain the support of the masses. This was a huge mistake. There was no way Japan wasn’t going to find out about this action; it was far too public. Infuriated(or at least acting infuriated), Japan seized control of the Korean government and disbanded their army.

Itō’s assassination

Activist groups formed to protest Japan’s treatment of Korea. In 1909, while Itō Hirobumi was travelling to Qing to meet with Russian officials, he was shot dead at Harbin train station by a member of one such group. Despite the fact he had held the position of Resident General and actively worked towards seizing control of Korea’s government, Itō had remained opposed to the idea held by many members of the Japanese government and army that Korea should be annexed. Korea’s last hope of gaining support from within Japan died with Itō. To make matters worse, as the assassination had occurred on Russian-leased land, Russia cut off all diplomatic ties with Korea. It had lost its last foreign ally. With no one to left to oppose Japan(most in fact in support of their actions), the government annexed Korea in 1910, officially integrating it into the Japanese empire.

In 1912, the emperor died at the age of 59. This marked the end of the Meiji era and the start of the Taishō era, as the Meiji emperor’s son ascended to the throne to continue his father’s work. Perhaps the emperor died at the perfect time, living just long enough to see his empire at its height without having to witness the economic struggles, social unrest and natural disasters that would set his country on a path to the dark side. Join me in the final part of this overview of Japanese history to discover the fate of the Japanese empire in the Taishō and Shōwa eras.