Japanese history overview Pt. 11: The Taishō/Shōwa eras

We’ve reached the final part of this overview. For those of you who have stuck with it from the very beginning, thank you! For those of you who jumped in here for information on the Taishō/Shōwa eras, you have no idea how long this thing has been!! I was really hoping to keep it to ten parts, but Japanese history wouldn’t allow it; it’s just too long! And so, in the infamous words of Nigel Tufnel… These go to eleven.

This section of the overview does come with a disclaimer, however. For those of you with an affinity towards Japan, this might be a difficult read. I’m sure you all know to some extent what I’m talking about. Anakin is turning to the dark side. The Dragon Queen is close to succumbing to her true nature. Walter White is about to discover his calling in life. Now that I’ve got all the pop references out of my system, let’s begin in 1912―the start of the Taishō era.

The Taishō era

The First World War

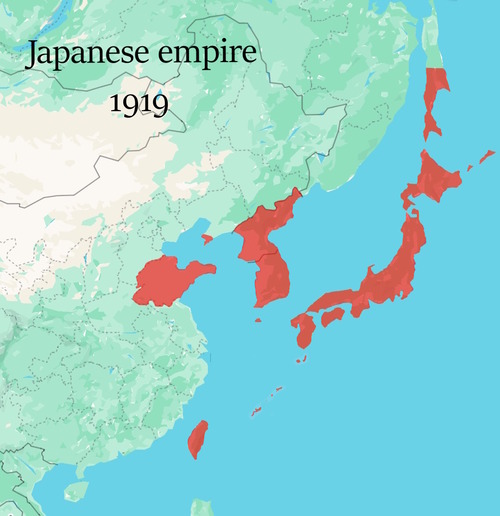

It pretty much goes without saying that the first major event of the Taishō era was the First World War. As part of Japan’s alliance with Britain, it was brought into the war to take down German-occupied territories in China. In return for its troubles, it was awarded the rights to Shandong as well as control over all formerly-German-occupied islands in Asia north of the equator. Several years earlier, Qing lost a civil war, resulting in its country being reborn under the name of ‘The Republic of China’. The Western nations decided it was only fair that this newly-formed nation be given a chance to develop itself and catch up with the rest of the world. And so all countries were made to return the land they had been leasing for the past twenty or so years. No sooner had Japan gained control of Shandong than it was forced to part with it.

It wasn’t all bad, though; at the same time, Japan was named a council member of the newly-formed League of Nations―an international organisation established for the purpose of maintaining world peace. Territorial issues aside, the war actually turned out to be extremely profitable for Japan too. As its participation was limited, the government didn’t need to resort to conscripting the general populace to go and fight for them. This meant they had more people free to work in factories and produce the fabrics and metals necessary for the countries who played a larger role. Moreover, since those countries now lacked the means to produce these items for even themselves, there was no way they were going to be able to produce enough to export to their regular customers in Asia and Africa. This was the perfect opportunity for Japan to step in and scoop up the entire customer base of the Western world. Farmers were ushered into factories en masse to produce enough silk threads, cotton, chemicals, metals, machines and ships to meet global demand. Needless to say, this made Japan phenomenally wealthy in a very short space of time.

The rice crisis

This wealth came at a cost, however. With a significant number of farmers having switched professions, rice prices began to rise, bringing about a rice crisis. This problem was exacerbated further when the USA called on Japan to join them in Siberia for a mission to rescue Czech soldiers who were being held prisoner by the Soviet army. Merchants were well aware that the government would need a vast rice supply to feed the country’s soldiers while they were away on this potentially long mission. And so they began to buy up rice supplies in bulk with a view to selling them to the government at inflated prices. This caused the value of rice to soar to the point the general population struggled to eat. Riots broke out all over the country. The police being powerless to stop them, the army had to be called in to restore order. Even after the riots were over, rice prices continued to rise until 1920.

The media pounced on the chance to put the blame on Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake and get the people to put pressure on him to resign along with his cabinet. He was replaced by Hara Takashi, Japan’s first ‘commoner’ prime minister―the first prime minister to have risen to the position without ever having been awarded a noble rank. This quelled the people’s anger somewhat. They were delighted to finally have a leader they could relate to―someone who had come from a background similar to theirs. However, just three years later, Hara was assassinated by a train driver who opposed his policies.

Taishō democracy

The rice riots of 1918 awarded the people a newfound confidence; having brought about the resignation of a prime minister, they realised that if they stood together, they were more powerful than the government. As Hara Takashi’s situation showed us, however, some had become too radical. Politicians would have to tread carefully if they not only wished to keep their positions but also their lives.

Subsequent leaders struggled as protests and demonstrations persisted. People wanted the biased voting rights decided upon in 1890 altered to allow every last one of them a say in the way the country was run. Hara Takashi had tried to meet them halfway in 1919 by lowering the tax conditions for voters to 3 yen from 15 yen, raising the number of people eligible to vote from 1.1% of the population to 5.5%, but it wasn’t enough. The people continued to protest until eventually, in 1925, the tax restrictions were removed entirely, allowing all men over the age of 25 the right to vote, and any man over the age of 30 the right to run for office. It would take women a further 25 years to receive these same conditions, however.

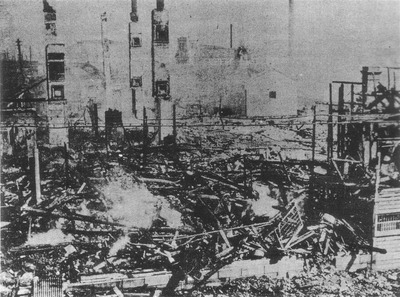

The Great Kantō Earthquake

Let’s go back a few years to 1923 because no overview of the Taishō era would be complete without mention of one of the biggest disasters to befall Japan in all its history: The Great Kantō Earthquake. 7.9 on Japan’s magnitude scale, it is one of the largest earthquakes ever to have struck the country. That said, Japan experiences earthquakes of this magnitude every 20 years or so. What made this one stand out is the fact that it occurred at 11:58 a.m., right when people were in the middle of cooking lunch. As many households still used charcoal grills at the time, the earthquake caused fires to erupt all over Tōkyō. The city burned for three days. When the fires finally died down, 105,000 people had lost their lives, and 40% of the metropolis lay in ruins. The cost of the damage was estimated to have reached 5.5 billion yen―one third of Japan’s GDP. Many factories and wholesalers also burned to the ground, driving various industries to a halt. All the profit Japan had made from the war went up in flames. The country was impoverished once more.

In 1926, the emperor died of illness at the age of 47, marking the end of the Taishō era. His son ascended the throne, ushering in a new era: Shōwa.

The Shōwa era

Manchuria

The Shōwa era begins with Japan struggling to break into China―a newly-formed nation still struggling to iron out all the creases in its new government. The country was undergoing a kind of battle royale as various political groups seized control of different regions and battled to become the leading power. Japan took advantage of this chaos in order to get a foothold in the country, opting to back Zhang Zuolin, the man in charge of a substantial chunk of land to the east of the country known as Manchuria. This area was rich in iron and ore, which made it very attractive to Japan―a country still struggling to recover financially from the earthquake that had struck it five years prior.

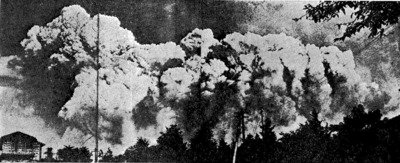

Manchuria wasn’t secure, though; Chiang Kai-Shek, leader of the Nationalist Party, was leading his men north, gunning for Zhang. Worried that Japan’s Kwantung army wouldn’t be enough to hold off the advancing enemy, Zhang turned to Europe for support. Needless to say, Japan wasn’t happy. And so in 1928, the Kwantung army killed Zhang by blowing up the South Manchuria Railroad as his train passed over it. Zhang’s son, Xueliang, took over his father’s army and assumed control of Manchuria. However, when he learned that Japan was responsible for his father’s death, he convinced Chiang to join forces with him and handed over Manchuria, slamming the door shut in Japan’s face.

One year after being squeezed out of Manchuria, the American stock market crashed. This had a knock-on effect on the world, resulting in mass unemployment, bankruptcy, and the closing of banks all over Japan. The economic crisis the country had been facing for the past six years had just been made significantly worse. The need to occupy Manchuria was all the greater. In 1931, the Kwantung army hatched a plan to blow up a part of the Southern Manchuria railroad(again!) and blame it on Zhang and Chiang. The plan worked brilliantly; having made it appear as if China was trying to sabotage the industrial work Japan had conducted to develop the region, the Kwantung army now had the perfect excuse to re-enter, drive out the Nationalist Party’s army, and seize the area. Furthermore, to avoid giving the impression that they were only interested in taking control of Manchuria for personal gain, they declared the region an independent state and installed Qing’s last emperor, Puyi, as its ruler.

Shōwa prime ministers

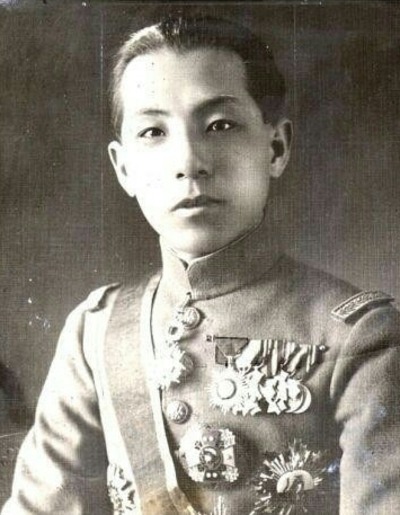

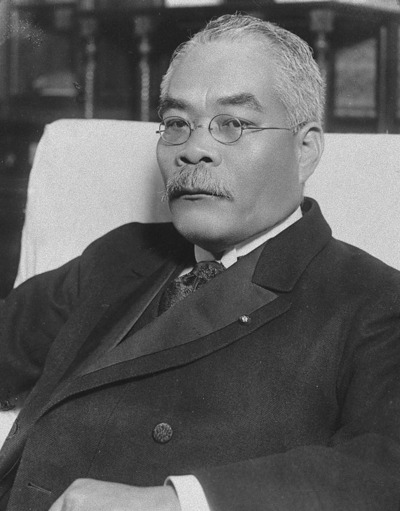

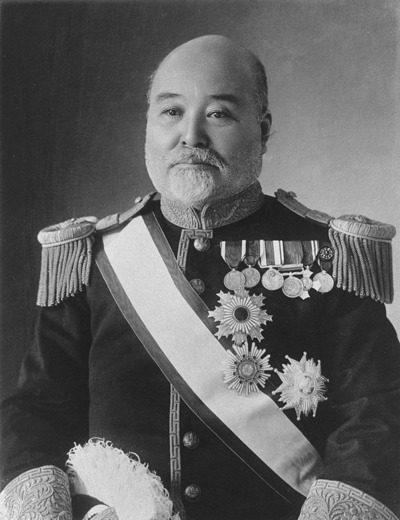

Back home, the government was less than impressed with the army’s achievement; none of their actions since the first explosion of 1928 had been sanctioned. In fact, after finding out about the assassination of Zhang Zuolin, the emperor was so furious that the prime minister at the time, Tanaka Giichi, was made to take responsibility for the entire affair and step down. His successor, Hamaguchi Osachi, was shot by an activist who believed that Hamaguchi had infringed on the emperor’s right to control the army by agreeing with the USA to limit the number of naval vessels Japan was allowed to hold. Although Osachi survived the attack, it weakened him to the point he was no longer able to govern the country, and, a year later, it became the indirect cause of his death.

Hamaguchi’s successor, Wakitsuki Reijirō, opposed the actions of the Kwantung army and ordered their commander to halt any plans he had to expand Manchuria. The army ignored his order. No longer able to subdue them, Wakitsuki lost the support of his peers and was forced to step down. The next challenger to enter the arena was Inukai Tsuyoshi. He too had a go at trying to get the army under control, but a year into his term, he was assassinated by a group of young army cadets who had just returned from Manchuria.

The path to the Dark Side

At this point, it’s incredible to think that anyone would even want to be prime minister! Nevertheless, a country needs a leader, and someone has to assume the role regardless of the risk. The next man to put his life on the line was Saitō Makoto. Having learned from the mistakes of his predecessors, he took a far more lenient approach towards the Kwantung army, giving them the green light to expand Manchuria. While this obviously pleased the army, it gave rise to a new problem: China wasn’t happy. After all, you wouldn’t be if another country marched into your land and ripped out a huge chunk of it for themselves, would you? And so, China launched a formal complaint with the League of Nations, who sent a team from Britain to investigate the matter. After a thorough investigation, the team concluded that Japan’s actions weren’t befitting of a council member of the League of Nations. They offered Japan an ultimatum: return Manchuria or quit the league. Japan opted for the latter.

Seeing what the global economic crash had done to their country, many began to turn away from capitalism, believing that it was corrupt politicians and their ties to wealthy conglomerates that was responsible for the mass unemployment and starvation they were facing. Some believed that if the corrupt element of the government could be extracted, the emperor would be free to rescue them. In 1936, a group of 1,500 soldiers took it upon themselves to conduct such a plan. After taking over a number of key police and army facilities, they split up into various groups and assassinated Saitō Makoto, Takahashi Korekiyo(minister of finance and former prime minister), and the inspector-general of military training. They had also planned to kill the current prime minister, Okada Keisuke, but ended up accidentally killing his brother-in-law instead, mistaking him for their target.

These renegade soldiers’ actions quickly gained mass support from many in the army and navy, but when the emperor declared them enemies of the state, that support quickly waned. They had set out to free the emperor from those they considered to be his enemy, but in the process had become his true enemy. Shocked at having been branded traitors, they put down their weapons and surrendered. Many took their lives. Others handed themselves in, leaving their fate in the hands of the state. Regardless of the whole affair, however, the army still maintained its chokehold over the government. Prime Minister Okada stepped down and was replaced by Hirota Kōki, who tripled the army’s budget and relied heavily on their input with regard to his cabinet choices.

If you’re interested in knowing how the rest of the wartime period prime ministers fared, take a look at the table below.

Prime Minister | Term | Fate |

Tanaka Giichi | Apr 4, 1927 – Jul 2, 1929 | Forced to step down after the assassination of Zhang Zuolin. Died several months later. |

Hamaguchi Osachi | Jul 2, 1929 – Apr 14, 1931 | Shot by a radical who believed Osachi had infringed on the emperor’s authority. Health gradually declined as a result until he died nine months later. |

Wakatsuki Reijirō | Apr 14, 1931 – Dec 13, 1931 | Forced to step down over his inability to control the army and prevent the Manchurian invasion. |

Inukai Tsuyoshi | Dec 13, 1931 – May 16, 1932 | Assassinated by a group of young naval officers. |

Takahashi Korekiyo | May 16, 1932 – May 26, 1932 | Assassinated by a group of rebel military officers in the February 26 Incident. |

Saitō Makoto | May 26, 1932 – Jul 8, 1934 | Assassinated by a group of rebel military officers in the February 26 Incident. |

Okada Keisuke | Jul 8, 1934 – Mar 9, 1936 | Targeted by rebel military officers in the February 26 incident. Stepped down less than two weeks after the incident. |

Hirota Kōki | Mar 9, 1936 – Feb 2, 1937 | Sentenced to death by hanging for war crimes. |

Hayashi Senjūrō | Feb 2, 1937 – Jun 4, 1937 | Pressured to step down after just four months due to dissatisfaction over his actions with regard to the assembly. |

Konoe Fumimaro | Jun 4, 1937 – Jan 5, 1939 Jul 22, 1940 – Oct 18, 1941 | Committed suicide in 1945 to avoid facing trial for war crimes. |

Hiranuma Kiichirō | Jan 5, 1939 – Aug 30, 1939 | Sentenced to life imprisonment for war crimes. Spent six years in prison before being paroled. Died shortly after his release. |

Abe Nobuyuki | Aug 30, 1939 – Jan 16, 1940 | Replaced after just four months due to lack of support from the military or any political parties. |

Yonai Mitsumasa | Jan 16, 1940 – Jul 22, 1940 | Forced to step down due to his opposition to an alliance with Germany and Italy. |

Tojō Hideki | Oct 18, 1941 – Jul 22, 1944 | Sentenced to death by hanging for war crimes. |

Koiso Kuniaki | Jul 22, 1944 – Apr 7, 1945 | Sentenced to life imprisonment for war crimes. Died two years into his sentence. |

The Second Sino-Japanese War

In July of 1938, while a Japanese troop was training on the Marco Polo bridge near Beijing, a group of Chinese soldiers opened fire. The prime minister at the time, Konoe Fumio, opted to make peace with the Chinese government, but the Kwantung army wasn’t having it. To smooth things over, Konoe made a compromise, allowing the army to send 200,000 additional men over to Manchuria. This, in turn, angered the Chinese army, who responded by performing a number of sneak attacks on the Kwantung army, who, when they finally reached their breaking point, spread out and began a full-scale invasion of all regions of the country. War had begun.

As the USA had numerous economic interests in China around that time, the last thing it needed was for the country to be at war. In order to scare Japan into ending the war, the American government broke off its trade agreement with the Japanese government and encouraged Britain to follow suit. Britain and France began supplying China with weapons. Japan was alone. The government needed a new ally fast.

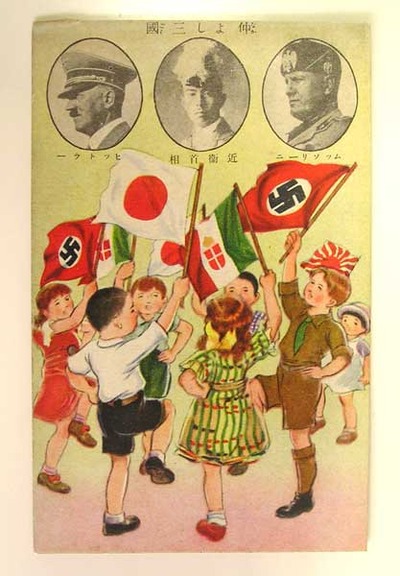

The Tripartite Pact

As luck would have it, one other country was in the market for a new ally: Italy was experiencing a similar situation to Japan in that it had invaded Ethiopia in the mid-30s and been given the same ultimatum by the League of Nations that Japan had received. Both Japan and Italy were in dire need of assistance, and who better to provide it than the new enemy of their former allies who had turned their backs on them. The year was 1939. The Second World War had begun. The two lonely nations teamed up with the world’s greatest villain: Germany.

Perhaps it was inevitable that the three countries would join forces at some point, bonded by their shared hatred of the Soviet Union. Japan hated the Soviets due to the fact that it had been at war with Russia(as the Soviet Union was formerly known) 30 years prior, and Russia had always stood in the way of Japan’s attempts to secure Korea. Italy hated the Soviets because communism had spread south and was becoming a major influence on its society. Germany hated the Soviet Union since it was home to a large Slovakian population, whom Hitler wanted to eradicate. The Tripartite―the most terrible alliance of the 20th century―had been formed.

The ABCD Line

In 1941, the USA put further pressure on Japan by convincing Britain, Holland, and China(who obviously didn’t need much convincing) to place an embargo on oil. Naturally, this extended to all colonies held by those countries and all associated Asian countries. Japan referred to this sanction as the ABCD Line, named after the countries who imposed it upon them: America(A), Britain(B), China(C) and Holland(D). (The ‘D’ came from ‘Dutch’. It was a little forced, but necessary to form the catchy name.)

With only 18 months’ worth of oil in its reserves, the army began to panic. The government tried to negotiate with the USA, but the American government wouldn’t accept anything less than a full retreat from China. In November, they issued their final ultimatum: leave China, abandon all interest in the country and cancel the alliance made with Germany and Italy. This was later viewed by historians as a tactic to goad Japan into declaring war on the USA. President Roosevelt had managed to secure a third term in office by promising the American people that the country would not join the war. However, with France out of commission and Britain struggling, the Allied Powers were in desperate need of support. The only way Roosevelt could convince the people of the need to join the war was to have Japan attack first. This would provide him the perfect excuse to launch a counter-assault on Japan’s number one ally, Germany.

The Pacific War

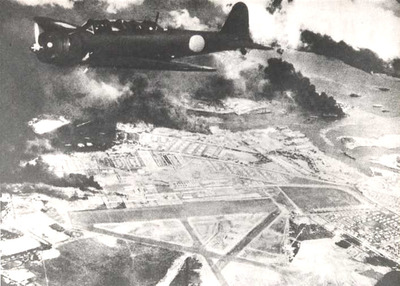

Pearl Harbour

Japan had no intention of ending its war with China, but, on the other hand, with oil supplies dwindling, it looked unlikely that the army would be able to see the war through to the end. The country’s only option was to defeat the USA and force it to remove the oil sanction. That wouldn’t be easy though; the US army was almost twice the size of the Japanese army. They would have to deliver an initial blow powerful enough to damage America to the point of incapacitation. On December 8, 1:30a.m., Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. The sneak attack succeeded in destroying four battleships, damaging a further four and killing over 2,000 soldiers. This was the excuse Roosevelt needed.

In many ways, the attack on Pearl Harbor can be viewed as the beginning of the end of the Second World War: not only did it bring America into the war, but it also hindered Hitler’s plan of having Japan invade the Soviet Union and forcing it to divide its army. With no one to keep the Soviets at bay, Germany risked having to face two of the largest armies in the world while one of its own allies was occupied fighting a war of its own halfway across the world.

Midway Atoll

From Japan’s perspective, however, it wasn’t so much looking to defeat the USA as it was trying desperately to secure a source of oil. In the six months following Pearl Harbor, the Japanese army not only managed to secure that source but also a route by which to bring it home. This success didn’t last long, though; in early 1942, the US intercepted Japanese telegram signals and managed to crack a certain code the army had been using to refer to one of their targets: Midway Atoll―a small stretch of land that lay between Japan and Hawaii. Having determined the date Japan intended to attack the atoll, the US was able to set up an ambush. This resulted in the destruction of four out of six of Japan’s aircraft carriers.

The Potsdam declaration

Things went downhill from there. Japan suffered defeat after defeat as the US took back most of the regions Japan had occupied in the early stages of the war. In 1945, the US Air Force closed in on Japan itself and began a series of airborne attacks, dropping bombs on all but a handful of the country’s major cities. In July, Germany surrendered to the allied forces. Italy had already surrendered two years before. Japan was alone once more. Knowing it wouldn’t be long before the government gave up, leaders from the US, Britain and China got together in Potsdam, Germany, to discuss the terms under which they would accept a surrender. They came to a mutual decision that Japan should recall all its troops, return the land it took from other countries and agree to be occupied by the allied forces, who would help the country establish a new government.

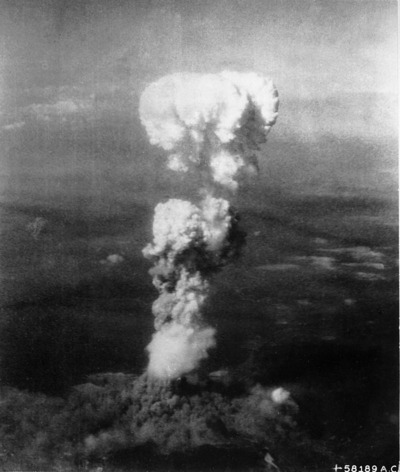

Before Japan could respond to these conditions, however, on August 6, the USA dropped a 15-kiloton atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The Japanese government gathered to discuss whether or not they should surrender. Before they could come to a decision, the USA dropped a 25-kiloton atomic bomb on Nagasaki on August 9. Six days later, the emperor made a radio broadcast to the people of Japan announcing the nation’s official surrender. The war was over.

GHQ

Shortly after Japan’s surrender, the US established the General Headquarters(GHQ)―the organisation under which the Allied Forces’ occupation of Japan would be conducted. General Douglas MacArthur was granted the title of Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces and sent to Japan to oversee the operation. The GHQ tried all soldiers and officials involved in the war. In total, seven were given the death sentence and 16 were sentenced to life imprisonment. Elsewhere, as promised by the USA, MacArthur’s team worked with Japan to help the country establish not only a new government but also a new constitution―one more in line with the ideals of the Western world. During their seven-year occupation of Japan, the GHQ influenced government and economic policy, workers’ rights, women’s rights(women finally got the right to vote), education and agriculture. By the time they left, the country had undergone a complete makeover.

The Korean War

While Japan was getting back on its feet, however, Korea was struggling. Japan’s defeat had granted the nation its independence once more, but having been ruled by another country for 35 years, the Korean people had no idea how to go about forming a government of their own. The Soviet Union and the USA stepped in, taking control of the north and south regions of the country respectively. The plan was to give each a crash course in politics before unifying them. However, several years later when the time came to unite the two regions, the North refused; the Soviet Union had taught them everything they needed to know to become an independent Communist state. North Korea was born.

Unable to find a way to coexist, Korea and North Korea went to war in 1950―a war that still continues to this day. Despite having indirectly been the cause of this war, it ended up being exactly what Japan needed to restore its economy: as it was the closest US-controlled region to Korea, the American army used Japan as its base of operations. People flooded to factories to manufacture weapons, equipment, and supplies. Japan experienced an economic boost the likes of which it hadn’t seen since the First World War.

Two years into the war, after having occupied Japan for seven years, the GHQ left. The Japanese government having been more cooperative than expected, the American government decided their time was better spent elsewhere. Japan was free to govern itself once more.

Redemption

Four years later, in 1956, Japan was invited to join the United Nations. The same year, the government signed an agreement with the Soviet Union, officially ending the war between the two countries and agreeing to restore diplomatic relations. It took until 1965 to be able to sign a similar agreement with Korea, however. Finally, in 1978, Japan signed a peace treaty with China, officially putting an end to all hostilities with all its former enemies. And having been selected as the location for the 1964 Summer Olympics and the 1970 World Exposition, the country needed no further evidence that it was now viewed as an equal by the nations it had opposed in the war.

The death of the Shōwa emperor in 1989 marked the end of the Shōwa era―the longest era in post-Meiji Restoration Japanese history to date. It also marks the end of this overview of Japanese history. I hope it’s been helpful. I might continue it one day into the Heisei era, but as Japan has been pretty relaxed since the war ended, there isn’t much to write about other than the occasional political dispute and natural disaster. Perhaps Reiwa will be more eventful. If this overview hasn’t quenched your thirst for knowledge, try taking a look through some of the other articles I have written and will continue to write from now on. Whatever form your studies take, I hope you continue to enjoy Japanese history!