Japanese history overview Pt. 4: The Muromachi era Pt. 1

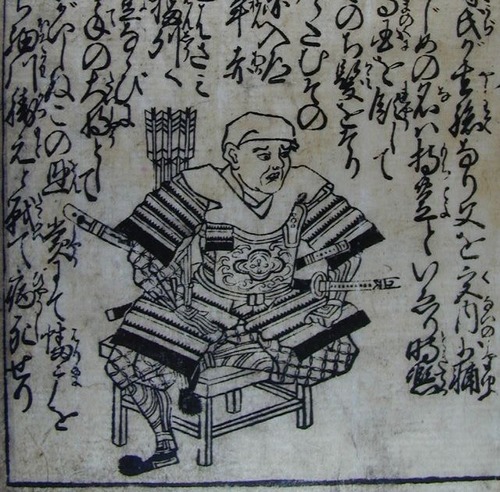

Welcome to part four of this overview of Japanese history. This time, we’re looking at the Muromachi era. As always, if you haven’t read the previous parts, I recommend doing so. Otherwise, you might not know who Ashikaga Takauji is or how he succeeded in toppling the newly-reformed court and establishing Japan’s second shōgunate. I apologise for this article’s confusing name, but the Muromachi era prove to be so long and complicated, I had to split its overview into two parts. A quick warning too… It’s going to get considerably more violent from now on. We’re really into the samurai age now! If you think of the Kamakura era as the training level for the samurai, then they’re ready to start the main game… on hard mode.

The Muromachi era blends nicely into Sengoku(which, let’s face it, is the reason 90% of you are here). But even before we get into Sengoku, the battle royale for control of the country is already beginning. Compared to other eras, very little happens during Muromachi in terms of politics, culture and art; it’s mainly violence. Also, fair warning, there are few pretty pictures or cute little royalty-free clip arts this time; this era needs a lot of explanation, so we have little time for anything other than maps and family trees. You’ll probably need to refer to both multiple times throughout this passage. For some parts, it might all be useful to keep Japan History’s map of ancient Japan handy too.

Hopefully, you’ll learn something. At the very least, I hope the complexity of this era doesn’t put you off Japanese history for good! If you need a break, stop and go back to Jōmon for a while. Chill with prehistoric man till you’re ready to come back and continue the gore fest. Enough with the exaggerations though. Let’s dive into the Muromachi era.

The Muromachi era: 1336 – 1573

In 1338, after defeating Emperor Go-Daigo and taking over Kamakura and the capital, Takauji was appointed shōgun. However, since he was much better at war than he was at politics, he left the administration of the shōgunate to his younger brother, Tadayoshi. This dual-leadership worked well for a number of years until 1349, when Tadayoshi had a disagreement with Kō no Moronao, one of the shōgunate’s top men. This escalated to a series of battles that resulted in Tadayoshi’s men killing Moronao and Tadayoshi being taken into custody. In the end, Tadayoshi killed himself. It’s unknown whether he was coerced into doing so or whether his brother played a part in it, but whatever the case, Takauji had sole control of the shōgunate from that point forth. His leadership didn’t last long, however, as he died in 1358―possibly as an indirect result of wounds incurred from the aforementioned battles.

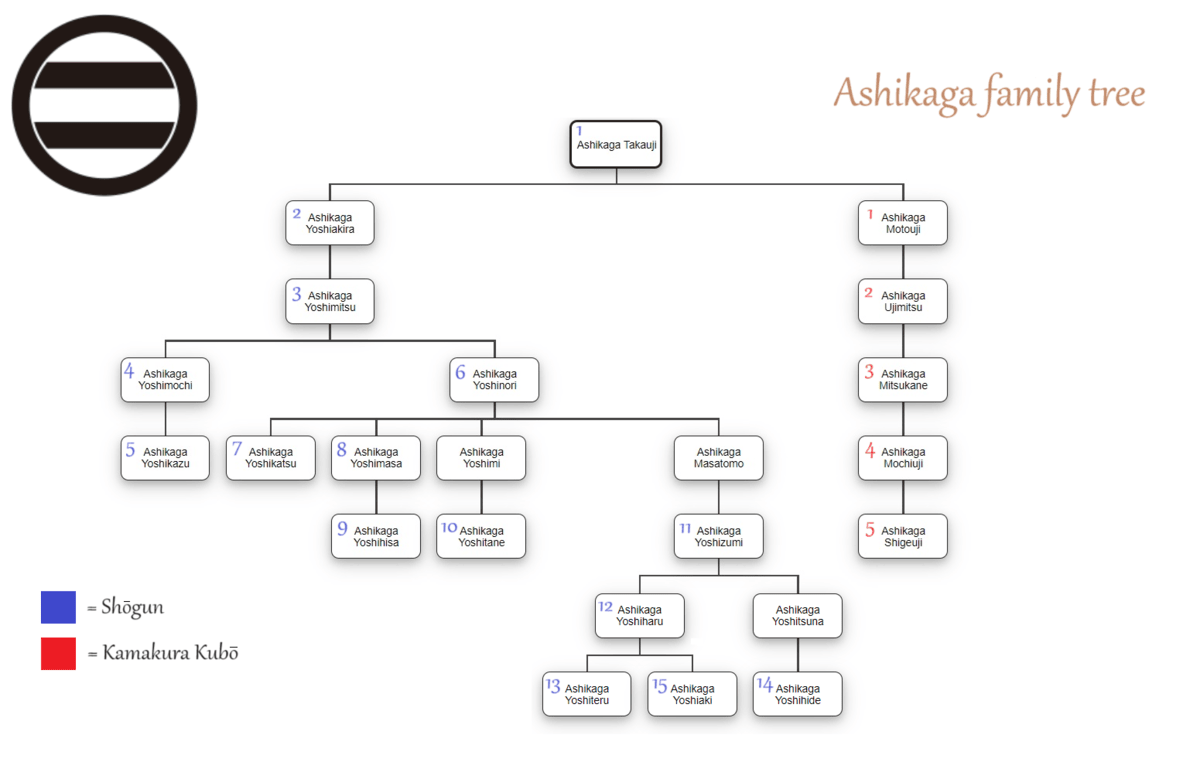

With the loss of his brother, Takauji called his son, Yoshiakira―who had been held hostage in Kamakura since Emperor Go-Daigo’s reign―back to the capital to help him run the shōgunate. In his place, he sent his fourth son, Motouji, to govern Kamakura under the title of ‘Kamakura kubō’. This role was supported by the ‘Kantō kanrei’―a role which would continue to be appointed to members of Takauji’s mother’s family, the Uesugi, until the end of the Muromachi era.

Ashikaga Yoshiakira

After his death, Takauji’s legacy was continued by Yoshiakira, who was stuck cleaning up the mess his father had left behind―namely, the fact that the court was still divided, and the two factions―the Northern and Southern courts―were at each other’s throats. During his time spent as shōgun, Takauji had someone to help him out with these problems: his right-hand man, Moronao. Yoshiakira too selected a right-hand man. This tradition eventually evolved into the role of ‘kanrei’―the second in command to the shōgun.

The role of kanrei was held throughout the Muromachi era by just three families: The Hatakeyama, Hosokawa and Shiba. Four more families were tasked with controlling the shōgunate’s private army and policing the capital: the Akamatsu, Isshiki, Kyōgoku and Yamana. Like the Ashikaga, all seven of these families had Minamoto roots. Considering the fact that Nitta Yoshisada―whom Takauji had defeated to take control of the country―also had Minamoto roots, and the fact that the Imagawa, Takeda and a number of other major samurai clans that played a part in this era all had Minamoto roots, most of the Muromachi era can actually be viewed as one big Minamoto family feud!

Outside of the capital, provincial regions were governed by shugo―a tradition passed on from the Kamakura era. Each shugo’s family was made to live in the capital to protect the shōgunate, while actual management of their region was conducted by the deputy shugo’s family. This allowed the deputies to amass power and form alliances within their territories that would eventually allow them to overthrow the shugo―a major factor in the events that led to Sengoku.

During his time as shōgun, Yoshiakira enlisted the help of a number of powerful samurai to help him fend off the invading Southern Court. The Ōuchi and Yamana in particular played major roles in turning the tides in favour of the Northern Court. Yoshiakira died in 1367 with the war still raging on, leaving his nine-year-old son, Yoshimitsu, to continue his efforts.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu

In 1392, Yoshimitsu finally put an end to the war between the two courts. Emperor Go-Kameyama of the Southern Court agreed to allow Emperor Go-Komatsu of the Northern Court to continue his reign on the condition that when he retired, he would pass the throne to Go-Kameyama’s son. Both parties agreed to alternate ascensions between the two courts from that point forth(which is essentially what they had agreed to back in the Kamakura era when the succession dispute initially started. I guess they forgot how badly that arrangement went). However, when Emperor Go-Komatsu was ready to retire, he ignored his promise and passed the title to his own son. The Southern Court continued to contest the decision and oppose the new emperor with their dwindling forces, but eventually lost wind after a few decades and faded out of history.

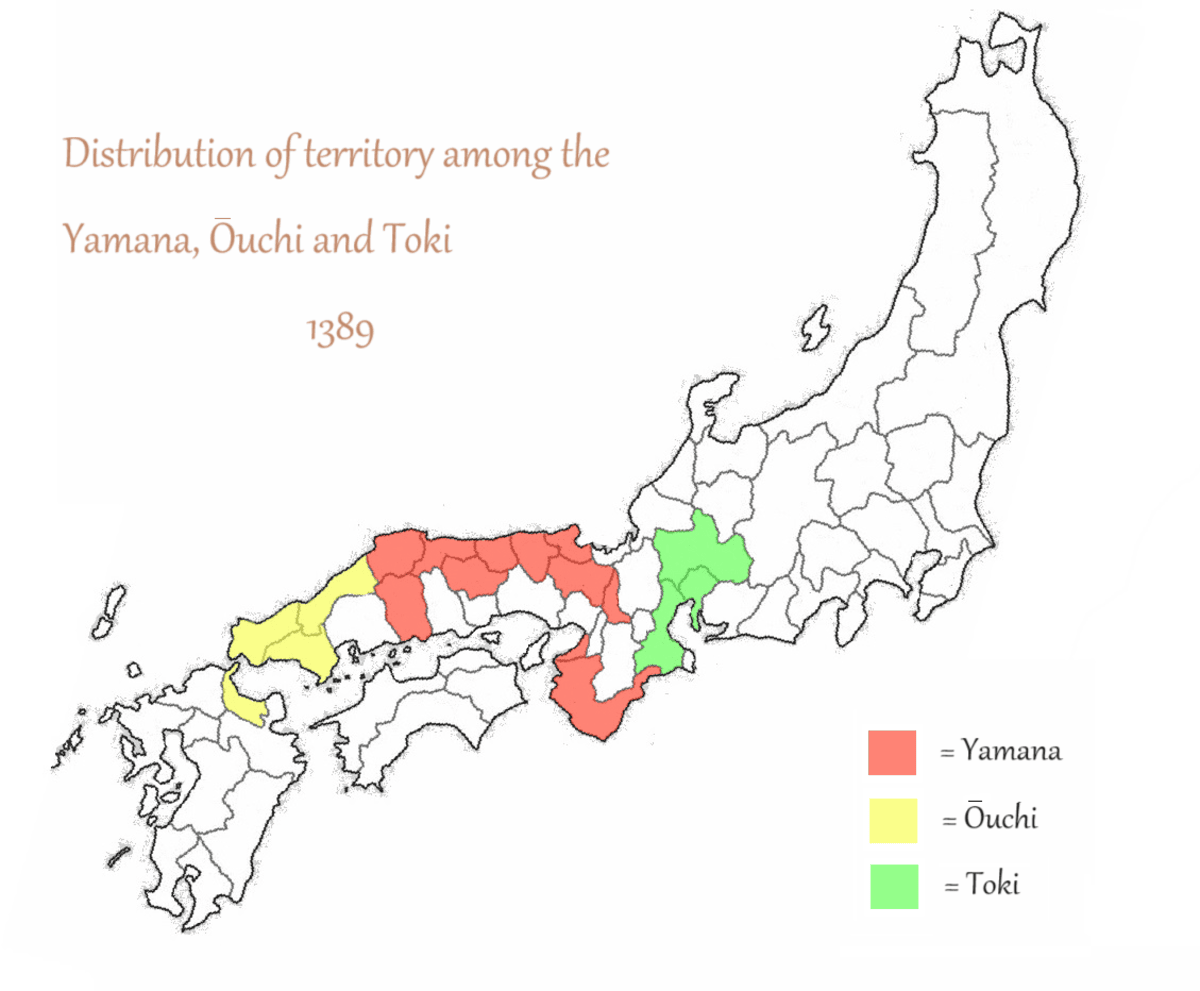

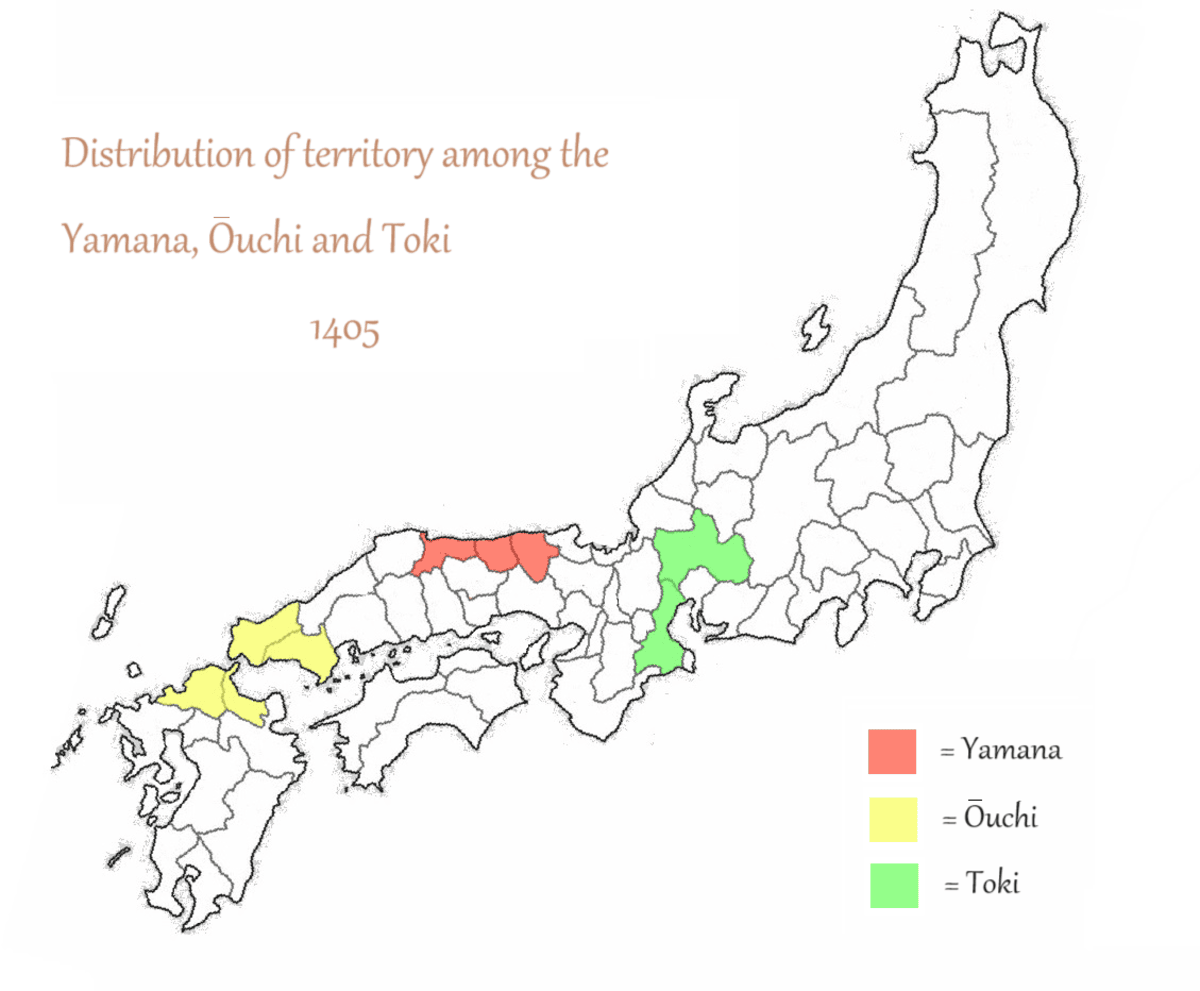

So now that the two courts were ‘united’, everything was okay, right? Well, not exactly. In ending the war, the shōgunate had inadvertently created a new problem: some of the major families whose services he had employed to help him fight the Southern Court had become too powerful. In exchange for their armies, Yoshiakira and Yoshimitsu had granted them vast areas of land, which had allowed them to increase their influence within the shōgunate to an alarming level. The Yamana in particular now controlled one sixth of the country! Yoshimitsu spent a good number of years tricking the Yamana, Toki and Ōuchi families into rebelling against the shōgunate so he could have an excuse to subdue them and confiscate their land.

A brief period of peace

This culling of the major players ushered in a period of peace the country had not enjoyed for almost one hundred years. However, it was a mere respite in the fighting, which would quickly recommence and continue for a further two hundred years! Yoshimitsu began trading with Ming, exporting swords, spears and folding fans, and importing silk, books, artwork, and bronze coins. These coins would later become the chief currency of the Muromachi era.

Yoshimitsu retired to the north of Kyōto, where he built a mountain villa as part of the temple complex of Sōkokuji―a zen temple he constructed during his time as shōgun. The villa was named ‘Rokuonji’, but it would later earn the nickname ‘Kinkakuji’, meaning ‘Golden Pavilion’, due to the fact it was covered entirely in gold leaf. Although this temple burned down in the 20th century, it was reconstructed soon after. Today, it is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Kyōto. After passing the title of shōgun to his son, Yoshimochi, Yoshimitsu continued to run the country behind the scenes from the comfort of his villa.

Another of Yoshimitsu’s accolades was his decision to move the shōgunate to the Muromachi area of Kyōto(hence the era’s name), and construct Hana no gosho―a ‘palace’ similar in size and shape to the Imperial palace and just a stone’s throw away from it. (I guess he was really trying hard to assert his dominance.) To sum up his term as shōgun, everything Yoshimitsu touched turned to gold(literally, in the case of Rokuonji). However, as is often the case in feudalistic societies(or democratic societies for that matter), a great leader tends to be followed by someone… not so great.

Ashikaga Yoshimochi

Yoshimochi didn’t have a good relationship with his father; from a young age, he began to believe his father preferred his younger brother, Yoshitsugu, whom he also came to resent. And so when Yoshimitsu died in 1408, Yoshimochi set to work destroying everything his father had created. He moved the shōgunate from Hana no gosho to the former residence of his grandfather, Yoshiakira. He tore down every building his father had constructed, except for Rokuonji. He undid all the ties his father had created with the major samurai families, and he put an end to the trade agreement with Ming. In short, he set the country back twenty years.

When the Kantō kanrei started a small rebellion in 1416, Yoshimochi took the opportunity to claim Yoshitusgu’s involvement and have him executed. With his enemies and rivals eliminated, he passed the title of shōgun to his son, Yoshikazu, and retired. He wasn’t able to enjoy his retirement long, however, as Yoshikazu developed a serious alcohol problem, which led to his death at the age of 19. With no other sons to assume the role, Yoshimochi had no choice but to reinstate himself.

Yoshimochi died in 1428 without having named a successor, leaving the shōgunate with a bit of a conundrum; the only remaining members of the Ashikaga family of a suitable age to run the country were the other sons of Yoshimitsu, who had all been sent to join the priesthood at early ages in order to avoid a succession dispute(ironically). This served well for Ashikaga Mochiuji, the Kamakura kubō at the time, who fully believed his chance had finally arrived. However, contrary to his expectations, the shōgunate decided to hold a lottery to decide which of Yoshimitsu’s sons to call back from the priesthood and install as the 6th shōgun. The lottery was held at Iwashimizu-hachimangū, a shrine with significant ties to the Minamoto family. Yoshinori won.

Ashikaga Yoshinori

Mochiuji was furious at the decision. And so, he started a rebellion. Yoshinori sent his army to defeat Mochiuji, and ordered the Kantō kanrei, Uesugi Norizane, to execute him. Two of Mochiuji’s sons escaped, but the shōgun’s army tracked them down and had them executed too. His youngest son, Shigeuji, however, managed to avoid this fate.

Yoshinori was infamous for dishing out extreme punishments. His favourites included forced retirement and execution. He once forced a court noble to retire merely for laughing during an official ceremony. When a certain maid didn’t pour his sake quite the way he liked, he shaved her head bald and forced her to become a nun. When a Nichiren-shū priest tried to lecture him, he poured a pot of boiling hot water over his head and cut off his tongue! These are just a few of the examples of the tyranny of Ashikaga Yoshinori.

A tyrant’s demise

In 1441, after having seen a number of influential samurai lose their position at the hands of the shōgun, a man by the name of Akamatsu Mitsusuke became paranoid that Yoshinori was coming for him next. And so, he invited Yoshinori to his residence for a banquet, during which he had his men surround and kill the shōgun. In preparation for the inevitable backlash, Mitsusuke barricaded himself inside his chief residence and waited for the shōgun’s allies to come and avenge their fallen leader. However, perhaps due to the fact that years of tyranny had severed most of Yoshinori’s ties with the majority of the powerful families, or perhaps due to the fact that few believed Mitsusuke could have pulled this off alone and that he must have been supported by a much larger army formed by all manner of unknown accomplices, no one wanted any part of the affair. It took three months before Yamana Mochitoyo finally got the guts to attack and kill Mitsusuke. This act put the Yamana back on the map and helped the family to regain a large portion of the land they had lost at the hands of Yoshinori’s father.

The Kyōtoku war

Yoshinori’s first son took over the role of shōgun but died just two years later at the age of nine. So his second son, Yoshimasa, became the 8th shōgun of the Muromachi shōgunate. Things were peaceful for a while until in 1454 Ashikaga Shigeuji―son of Mochiuji, who, if you’ll remember, led a rebellion against the shōgunate 15 years earlier―prove that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree by starting a new rebellion: The Kyōtoku War.

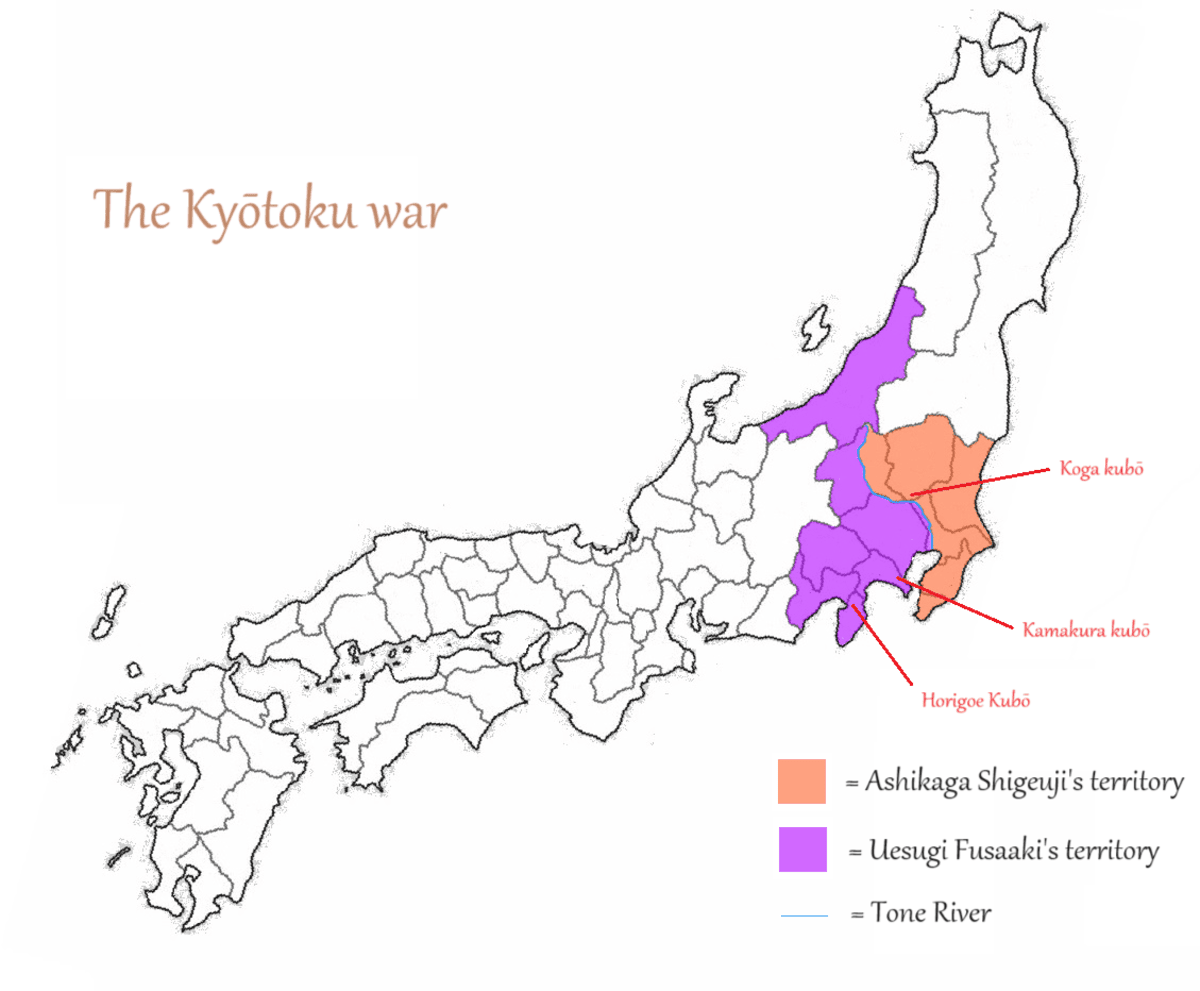

Shigeuji was just one year old when his father and brothers were killed. Not having had the chance to know his family, it’s unlikely he felt an instinctive need for revenge. However, since being given permission to resume his father’s role of Kamakura kubō, he had became privy to a number of stories regarding the Kantō kanrei’s treatment of his father―courtesy of some of the major families in the east, who presumably wanted to usurp the Kantō kanrei’s power. Taken in by their words, Shigeuji began to shun the Uesugi and surround himself with a new, cherry-picked crack team of powerful allies. This, understandably, infuriated the current Kantō kanrei, Uesugi Noritada(son of Norizane, who executed Shigeuji’s father), and caused him to attack Shigeuji’s new allies. Shigeuji retaliated, gathering his newly-built army and having them kill Noritada. This should have put an end to the conflict, but Noritada’s brother, Fusaaki, took over the role of kanrei and kept the war going.

Koga kubō

Several years in, while Shigeuji was busy fighting a battle in the far east, one faction of the Uesugi invaded and occupied Kamakura in its ruler’s absence, leaving Shigeuji no choice but to set up shop somewhere else. He chose an area of the country in Hitachi known as Koga to be his new territory, and began to refer to himself as Koga kubō. The shōgun, Yoshimasa, sent his brother, Masatomo, to be the new Kamakura kubō. The samurai of the east didn’t accept him, however, and he was forced to move west to the Izu peninsula and claim an area known as Horigoe instead. This series of events ended the role of Kamakura kubō and replaced it with two new kubōs: Koga and Horigoe. (From that point on, the title of kubō lost all meaning. Pretty much anyone could claim any area of land they wanted and name themselves ‘kubō’ of that land. From start to finish, the Muromachi era contained ten different kubōs.)

Both the Koga and Uesugi armies developed their territories across the Kantō plane, splitting the region more or less along the Tone river. The war raged on for 28 years until Shigeuji finally struck a deal with the shōgunate and had them intervene to put an end to the fighting. During the war, many leading clans’ branch families made deals with the Koga and Uesugi armies in bids to overthrow their families’ main branches. In the final few years, this trend spread to the provinces surrounding the capital. Having seen that the shōgunate was powerless to stop the war for a full 28 years and having witnessed a number of branch families in the east successfully take over leadership of their clans, samurai in the west figured they might as well get in on the action.

The Ōnin War

Among those who tried were two of the kanrei families: Hatakeyama and Shiba. The kanrei at the time was Hosokawa Katsumoto, who was married to the adopted daughter of Yamana Mochitoyo(who, you’ll remember, avenged Shōgun Ashikaga Yoshinori by killing Akamatsu Mitsusuke). Mochitoyo, who had entered the priesthood by this time, now went by his Buddhist name of Sōzen. He and his son-in-law had enjoyed a fruitful relationship for many years. However, several factors―including their dispute over the Hatakeyama family feud and the fact that Katsumoto returned a significant amount of land to the disgraced Akamatsu clan―led to the breakdown of that relationship.

To complicate things further, the shōgun, Yoshimasa, despite being 29 years of age, had not yet managed to produce an heir. With little prospect of being able to produce one in the near future, he decided to call his brother, Yoshiki, back from the priesthood to serve as his successor(a common theme in the Muromachi era, as you’ve probably noticed by now). However… Just one year later, miraculously, Yoshimasa’s wife, Hino Tomiko, gave birth to a son, who, when he came of age, would be named Yoshihisa. Yoshimasa assured his brother that he would fulfill his promise of making him the next shōgun. Tomiko had other plans; she was determined to see her son shōgun no matter what. Yoshiki feared for his position.

In summary, the Hatakeyama, Shiba and Ashikaga were all fighting amongst their respective families, and arguably the two most powerful men in the country, Hosokawa Katsumoto and Yamana Sōzen, were now rivals. Sides were taken, and before word of the situation could even reach neighbouring provinces, two massive armies stood on either side of the capital staring each other out. It all came to a head in 1467. The Ōnin war lasted 11 years and left the capital in ruins with the majority of its buildings destroyed. Towards the end, both Katsumoto and Sōzen died of illness, leaving their sons to carry on their work. Eventually, both sides became tired of fighting and led their troops back home, ending the war in a rather vague manner, without a discernable victor.

The road to Sengoku

So, to sum up the first 140 years of the Muromachi era, we’ve had the assassination of a shōgun, a 28-year war in the east, an 11-year war in the west and the destruction of the capital. Bear in mind, Sengoku hasn’t even started yet!! So if all that isn’t enough to be considered part of the Sengoku era, what distinguishes the Sengoku era from other periods of mass violence? One major difference is that while just the before the Ōnin war, it became possible for branch families of samurai clans to overthrow their clans’ main branch, entering Sengoku, it became possible for samurai clans to not only overthrow their shugo, but to also expand out and invade other provinces, creating their own mini empires.

All this became possible because of the Ōnin war. During the war, Hosokawa Katsumoto named Asakura Takakage shugo of Echizen in exchange for his switching sides. This placed the Asakura above both the deputy shugo and previous shugo of the region, the Shiba. In other words, the Asakura went from having almost no status whatsoever to being the top-ranking family of their entire province. This unprecedented act gave other families the impression that they too could overthrow their shugo and take control of their provinces. It threw the country into a 150-year long battle royale that saw the rise and fall of these mini-empires until one man finally took complete control of the country. (I’m going to keep this article spoiler free and hold off from telling you exactly who he is right now.)

So we’ve finally reached Sengoku―arguably the most popular period of all Japanese history. When people think of samurai, they picture the samurai of the Sengoku era―not the fledgling warriors of the Heian era, the budding politicians of the Kamakura era or the experienced bureaucrats of the Edo era, but the ruthless conquerors of Sengoku in their colourful armour and stylish kabuto helmets, marching thousands of men to their neighbours’ lands to take down their castles one by one and systematically destroy their network of retainers. All that and more to look forward to in part five of this overview of Japanese history.