Japanese history overview Pt. 6: The Azuchi-Momoyama era Pt. 1

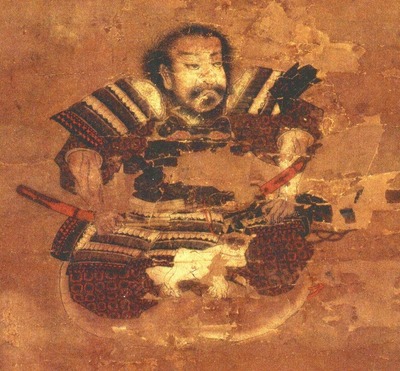

We’ve reached the 6th part of this overview of Japanese history. This part covers the Azuchi-Momoyama era, and that means the rise of Oda Nobunaga, the most powerful and, arguably, influential samurai of all time. When it comes to samurai, people tend to have a very specific image: lavish kabuto helmet decorated with gold ornaments, demonic masks, plated armour and long tachi swords. This is that very era! Samurai existed for over 1,000 years, during which time they went through a number of evolutions. But if you’re looking for larger-than-life celebrity warriors on which some of the most exciting historical novels, movies and games have been based, this is the period for you. Let’s dive into it.

Azuchi-Momoyama era: 1568 – 1603

Just 35 years in length, Azuchi-Momoyama is the shortest era in Japanese history(unless you count Taishō). However, to study this period in detail would take considerably longer than if you were to study all 400 years of the Heian era(believe me… I did it!). It begins with Oda Nobunaga’s storming of the capital and ends in 1603 with the appointment of a new shōgun(essentially the winner of Sengoku). We’re going to extend it to 1615, however, to cover the final battle of Sengoku―a fitting place to end this chapter before moving on to an era of peace.

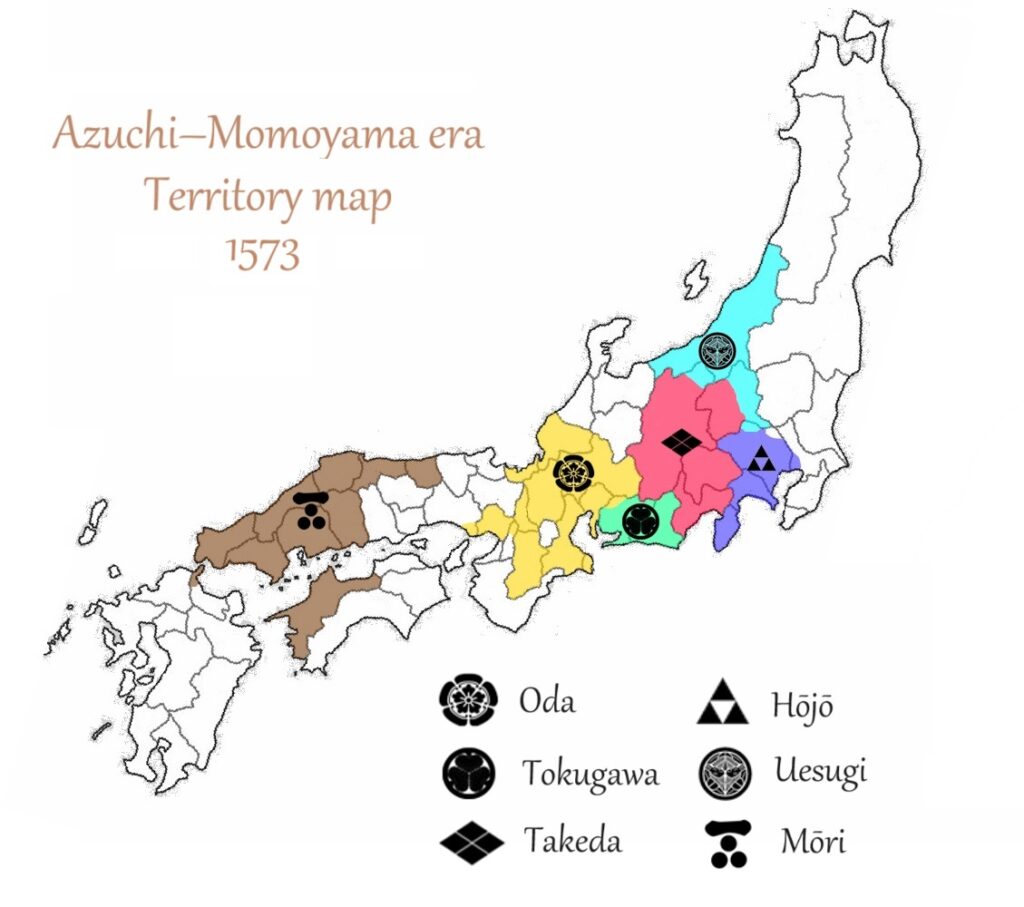

In 1573, with the shōgun out of the picture, there were no more puppets. The whole Miyoshi controlling the Hosokawa controlling the Ashikaga situation was over; the country was ready to be taken by anyone who had the guts to grab it. In that respect, the Azuchi-Momoyama era was a simpler time than the politically-minded samurai of the Muromachi era. On the other hand, the sheer number of samurai clans vying for the country makes this period arguably the most complicated. For that reason, I’m only going to focus on a handful of them. Some, I’ve already introduced: Oda, Takeda and Hōjō. Let’s add Tokugawa, Mōri and Uesugi to the mix. Before we look at who they are and how they affect the story, though, I think it’d be a good idea to do a brief comparison of their territories.

As it should be obvious to see, by 1573, Oda Nobunaga was already the major shareholder in the company that was Japan. While his territory was comparable in size to that of Takeda Shingen’s, whereas Shingen had spent almost 30 years expanding his empire, Nobunaga had taken just under 20 years. (Admittedly, being relatively close to the capital and allying himself with the shōgun did give him a considerable advantage.)

A love/hate triangle

Takeda

We already looked at the Hōjō in the second part of the Muromachi era overview. As you can see, they lost quite a bit of land to Takeda and Uesugi since we last saw them in the map of 1554. If you’ll remember, in that year they formed an alliance with the Takeda and were annihilating the Uesugi. So what went wrong? Well, after Nobunaga defeated Imagawa Yoshimoto in 1560, Yoshimoto’s son, Ujizane, limped on, his alliance with the Hōjō and the Takeda his last lifeline. But when his mother died in 1567, Takeda Shingen pounced. Ujizane’s mother had been the true brain of the Imagawa operation. Without her, the family didn’t stand a chance. Shingen formed a new alliance with Tokugawa Ieyasu, and together they conducted a pincer attack from the north and south of the Imagawa’s territory. When they’d destroyed the last of the Imagawa army, they divided up the land.

Hōjō

One man who was less than happy with this situation was Hōjō Ujiyasu, whose daughter was married to Ujizane. He instantly broke off his alliance with Shingen and replaced it with an alliance with the Uesugi―his former enemy―allowing him to focus his efforts on the Takeda. However, three years later when Ujiyasu died, his son, Ujimasa, reversed the situation, breaking off the Hōjō’s alliance with the Uesugi and reinstating their alliance with the Takeda(told you this period was complicated!).

Uesugi

As for the Uesugi, they weren’t the same Uesugi that had been forced to become Hōjō Ujiyasu’s plaything 20 years earlier. That Uesugi family was led by the Kantō kanrei of the time, Uesugi Norimasa, who had run off to the east after his son was killed by the Hōjō. The Uesugi weren’t just active in Kantō, however; they had relatives in Echigo, over to the east of Kantō. This branch had already been overtaken and made puppets by their top retainer, the Nagao clan.

Norimasa seeked refuge from Nagao Kagetora, whom he adopted and made the new Kantō kanrei in 1561. Having entered the priesthood at an early age, Kagetora had become most well known by his Buddhist name of Kenshin. Uesugi Kenshin ended up in wars with both the Takeda and the Hōjō, which had him leading large-scale campaigns to the east to try to reclaim the Kantō plain, while fending off Shingen’s intermittent invasions of his own territory.

Tokugawa Ieyasu

In summary, the situation as it stood in 1573 was that the Takeda and Hōjō were allied, and both were enemies of the Uesugi. Now let’s see how Tokugawa Ieyasu fits into all this. If you check back to the 1554 territory map from the Muromachi era page, you’ll see that the area of land now ruled by Ieyasu was previously under the jurisdiction of the Imagawa. In fact, Ieyasu’s hometown was also under the Imagawa’s jurisdiction. As such, in order to prove his loyalty to the Imagawa, Ieyasu’s father was forced to hand his son over as a hostage. Ieyasu lived out the majority of his childhood in Suruga, raised to be a general in the Imagawa army. It wasn’t until Oda Nobunaga took out Imagawa Yoshimoto that Ieyasu was able to declare his independence and return to his hometown.

Despite Yoshimoto’s death, however, turning on the Imagawa was still a risky move; Ieyasu had only a handful of retainers left in his hometown of Okazaki as opposed to the many families who remained loyal to the Imagawa. He would need a new ally if he was going to survive. Since most of the major clans east of his territory were still on the Imagawa’s side, he turned west towards Oda Nobunaga. Before becoming Imagawa Yoshimoto’s hostage, Ieyasu had spent a brief period of time as a hostage to the Oda(testament to the fact his family really was sandwiched in between two major powers. It was a miracle they managed to survive). The two formed an alliance in 1562 that would turn out to be one of the longest―and strongest―alliances of the entire Sengoku era.

That just leaves Mōri. But they won’t become a part of the main story until a little later. For now, all you need to know is that they were the major power west of the capital, which meant it was inevitable that they would eventually butt heads with Nobunaga.

Oda Nobunaga

sengoku’s strongest alliance

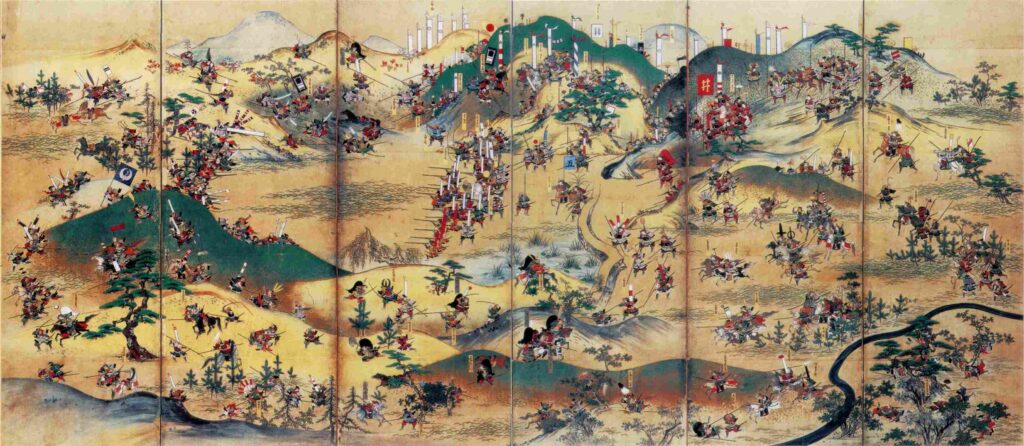

Returning to Nobunaga, 1573, if you’ll remember, was a busy year for him. Ashikaga Yoshiaki, the 15th and final shōgun of the Muromachi shōgunate, had called upon samurai everywhere to take him down. The Azai, Asakura and Miyoshi took on the challenge, but they all failed and lost their lives along with their territories. What I didn’t mention in the Muromachi article, however, is that there was another man who answered the shōgun’s call: Takeda Shingen. The Tiger of Kai(as he was nicknamed) led his men west to attack his former ally, Ieyasu, in a bid to expand his empire and clear a path to the capital, where he planned to face Nobunaga. His campaign started out well; he systematically took down Ieyasu’s castles and caused the young daimyō to suffer what would be the most embarrassing defeat of his career. In all likelihood, he would have made it to the capital had he not suddenly died of illness. Ieyasu and Nobunaga lucked out. Had Shingen survived just a few more months, the rest of the Azuchi-Momoyama era may have played out very differently.

Expanding an empire

Nobunaga wasn’t out of the woods yet, though; there was still one powerful enemy left: Ishiyama Honganji. The head temple of the Jōdoshin-shū sect of Buddhism had decided to join up with the Miyoshi back in 1570, and they had devout followers scattered all over the country. Nobunaga would spend ten years fending them off before finally forming a peace treaty. When he wasn’t fighting the might of Buddhism, he was busy teaming up with Ieyasu to take down castles belonging to the Takeda clan, which was now under the command of Shingen’s 4th son, Katsuyori. Nobunaga largely left this campaign in his ally’s capable hands while he sent his own men to the borders of his own territories to try to expand his empire.

To the north, he sent Shibata Katsuie, one of his most loyal retainers, who had gained his trust by turning on his(Nobunaga’s) brother―who had allegedly been plotting a rebellion―and switching sides. To the west, he sent Hashiba Hideyoshi and Akechi Mitsuhide. Hideyoshi had been with Nobunaga since his days of trying to take over the Mino province. His unique but effective strategies were indispensable to the campaign’s success. Mitsuhide had joined a little late in the game, but he is credited with having introduced Nobunaga to Ashikaga Yoshiaki, and, in addition, his cousin was Nobunaga’s wife. These two facts gave him a step up over the other retainers.

That covered the north, east, and west. The only area to the south not yet under Nobunaga’s control was Kī. This massive province was home to several major powers, including two temples, Neguroji and Kongōbuji, and the Saika clan―a powerful band of mercenaries skilled in the art of marksmanship, who had aligned themselves with the Ishiyama Honganji monks. Nobunaga would have to deal with Ishiyama first before attempting to enter the area.

Azuchi castle

And so, with his best men deployed around the country, Nobunaga set up a new base of operations in the east bank of Biwako―Japan’s largest lake―in the province of Ōmi. There, he set to work constructing the largest and most impressive castle of the time: Azuchi castle(from which half of the era’s name is taken). Unlike the mountain castles that had been the standard for most of the Sengoku period, Azuchi sported a 105-feet tall tower atop a large hill, which could be reached via a wide stone staircase that passed through a temple. Whereas most castles were built with the purpose of protecting their occupiers, Azuchi was a showcase of Nobunaga’s power. Its defences may not have been the strongest, but since Nobunaga controlled all the neighbouring provinces, that was no cause for concern. The tower was visible from all corners of the town that developed at the foot of the hill upon which it stood―a constant reminder to the merchants who worked and lived in the town of who was in charge. Azuchi became the model for the majority of castles that were built from that point on.

Tying up loose ends

Around the time construction began on Azuchi castle, Uesugi Kenshin began his campaign south, attacking Katsuie and forcing him back towards Echizen. The two fought hard for control of Kaga and Ecchū until 1578, when Kenshin suddenly died. Lucky for Katsuie, Kenshin hadn’t named a successor. An inevitable succession dispute broke out, which put a halt to the Uesugi’s expansion plans for close to two years.

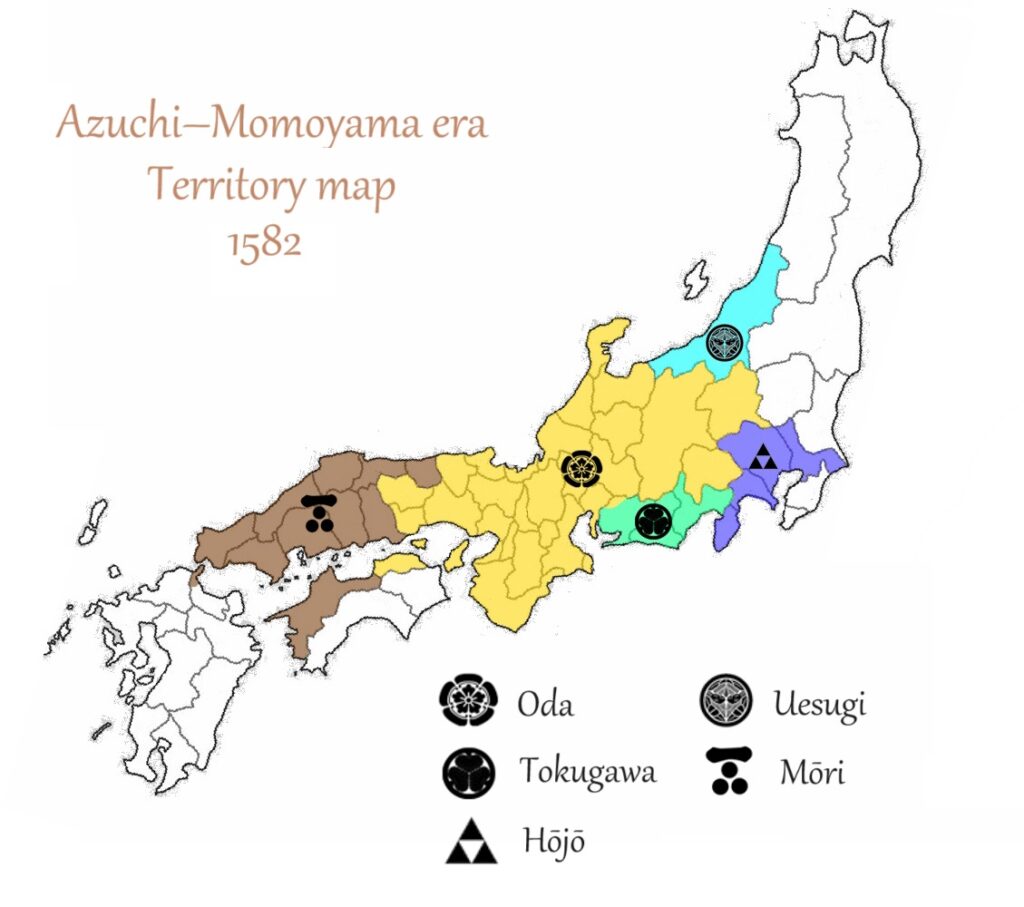

Nobunaga’s luck didn’t end there though; in 1580, after realising that the unstoppable warlord was only going to become more powerful, Ishiyama Honganji surrendered. And then, finally, in 1582, the moment Nobunaga had been waiting for arrived: Kiso Yoshimasa switched sides. Yoshimasa was a small feudal lord in the south of Shinano, married to Takeda Shingen’s daughter. His betrayal awarded Nobunaga the final route into the Takeda’s territory that he needed to launch his final campaign. Wasting no time, he contacted Ieyasu and had him attack from the south while he sent his eldest son, Nobutada, out east. Between them, they took down enough castles loyal to the Takeda to force Katsuyori out of his own castle. Realising he was cornered, Katsuyori and the last of his men ended their lives atop Mount Tenmoku.

With the Takeda’s portfolio of land added to his collection, Nobunaga now controlled around one third of the country. In addition, he had alliances with the Hōjō in the east, Date in the north and the Ōtomo in the far west. To top it off, Hideyoshi was in the middle of executing a plan that looked likely to force a surrender from the Mōri. The Oda empire was unstoppable. Or so it seemed…

The Honnōji incident

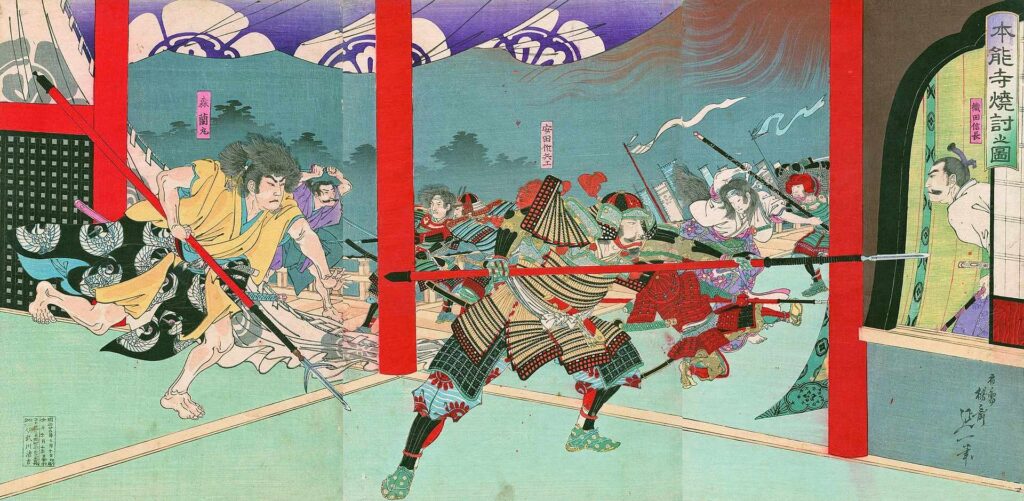

In June of 1582, just months away from having control over the majority of the country, the unthinkable happened. While Nobunaga was resting in the capital before making his way out west to assist Hideyoshi, Akechi Mitsuhide led an army of 13,000 and surrounded Honnōji, the temple where Nobunaga was staying the night. With less than 200 men to defend him, he didn’t stand a chance. The temple went up in flames. He made his way to the very back of the complex, where he took his life. To this day, no one knows for sure why Mitsuhide betrayed his lord, but one thing that is certain is the course of history changed dramatically that night.

Word reached Hideyoshi out west before any of Nobunaga’s enemies could know about this beneficial development. Hideyoshi quickly struck an agreement with the Mōri before their scouts could bring word back, allowing them to keep the bulk of their land in exchange for an alliance. The moment he secured the deal, he rushed his men back east, stopping at Himeji castle in Harima to pick up supplies and send scouts out to the neighbouring provinces in search of any allies who would be willing to join him at short notice. Several small clans agreed to join the cause. Just 11 days after Nobunaga’s death, Hideyoshi marched to the mountains west of the capital with an army of close to 30,000. Mitsuhide was waiting with the 15,000 men he had been able to muster up. It wasn’t enough to stop Hideyoshi’s thirst for revenge. Mitsuhide was killed while fleeing the battle.

The Kiyosu conference

When the dust had settled, Hideyoshi, Katsuie and two more of Nobunaga’s closest generals got together for a meeting at Kiyosu castle to discuss the future of the Oda empire. Since Nobunaga’s oldest son, Nobutada, had died along with his father, it was suggested that either Nobunaga’s second or third son, both of whom had been adopted out to other families, should be brought back to take charge of the family. Katsuie supported Nobunaga’s third son, Nobutaka. Hideyoshi had other ideas, however; he argued that since Nobutada had already officially succeeded the family at the time of his death, the next leader of the Oda clan should be his son, Sanbōshi. While logically this made sense, Sanbōshi was only two years old. Katsuie knew that Hideyoshi was planning to usurp power from the Oda clan as Sanbōshi’s guardian, but having been the one to avenge the clan’s fallen leader, Hideyoshi was already too powerful for anyone to stand against.

sengoku revived

Meanwhile, with Nobunaga dead, all hell broke loose in the east; since the Oda clan had taken control of the land previously ruled by the Takeda just three months prior, those put in charge of each region did yet not have the full support of the local samurai families, many of whom were unwilling to fight for their new masters. Fully aware this would be the case, a battle royale broke out between the Tokugawa, Uesugi and Hōjō, which lasted four months. Uesugi threw in the towel early on, leaving the other two clans to fight it out until they were able to come up with a compromise. Tokugawa Ieyasu got the lion’s share of the former Takeda territory but had to marry his daughter to Hōjō Ujimasa’s son in return.

Around the time the battle royale was coming to an end, tensions were beginning to fray between Hideyoshi and Katsuie. As per Katsuie’s expectations, Hideyoshi was making it increasingly obvious that he had no intention of handing over the Oda empire to Sanbōshi when the young heir came of age. It all came to a head early in the following year, when Hideyoshi attacked Katsuie and Hidetaka. Midway through the battle, Katsuie’s men began to desert him. By the time he himself fled, only a handful of his most loyal soldiers remained. He made it back to his castle, but there was nowhere left to run; his land was surrounded. Rather than hand himself over to the enemy, he set fire to the castle and died amidst its ruins. Nobutaka’s castle was surrounded by his own brother, Nobukatsu, who had chosen to side with Hideyoshi. Once Katsuie was dead, Hideyoshi had Nobukatsu order his brother to kill himself.

Hideyoshi Vs. Ieyasu

The following year―1584―Nobukatsu began to become disillusioned with Hideyoshi. He killed several of his own men whom he suspected of being Hideyoshi’s spies. As it turns out, his suspicions had been correct. There was no going back now. Desperately in need of an ally, he turned to the second most powerful man in the country: Tokugawa Ieyasu. Together, they advanced on Hideyoshi, who led his own men out east to meet the massive army. Due to the fact there was very little real antagonism between Hideyoshi and Ieyasu though, the two sides ended up spending months doing nothing more than stare each other down before finally deciding to fight. When the battles kicked off, Ieyasu had the upper hand. By the eighth month of the war, it looked as if he could actually defeat the country’s most powerful warlord. He may very well have done so too had Nobukatsu not started to feel pressured by Hideyoshi and forged a peace treaty. With no real reason to continue fighting, Ieyasu had no choice but to go along with this agreement and give up his chance at becoming the number one samurai in Japan.

And so with Hideyoshi having secured his place as the most powerful man in Japan, we’re going to take a break. Since I managed to sum up 230 years of the Muromachi era in two articles, I assumed the mere thirty-year long Azuchi-Momoyama era wouldn’t take more than a couple of thousand words at most. Nope! No wonder this is the most popular era of all Japanese history. Join me in part seven of this overview for the continuation of this epic story.