Japanese history overview Pt. 7: The Azuchi-Momoyama era Pt. 2

Welcome to part 2 of this overview of the Azuchi-Momoyama era. I really thought I’d be able to sum up this thirty-year period of Japanese history in one short article. How naïve I was. It turns out even two decently-lengthed articles isn’t enough to write half of what I want to say! Not to worry though; I plan on going into much greater detail on many of the people, places, castles and events of this era in more dedicated articles. For now, read on and familiarise yourself with what is arguably the most epic time of all Japanese history. As always, refer to the map of ancient Japan whenever you need to.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

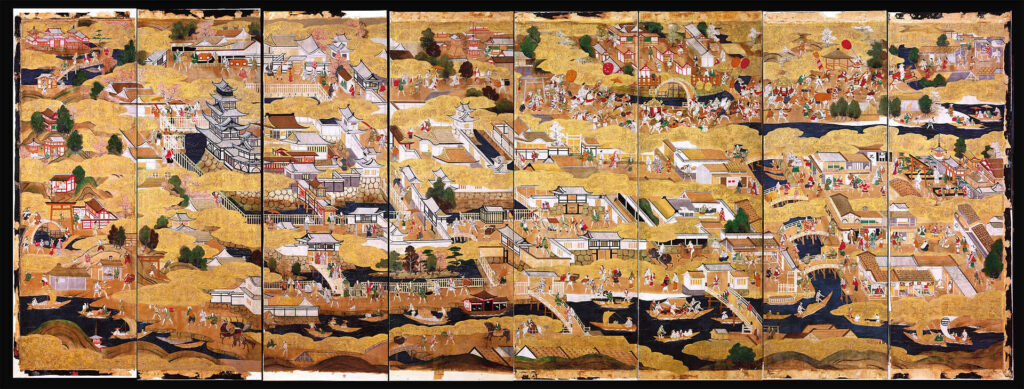

With all his political enemies defeated, Hideyoshi had some breathing room. In 1585, he moved into Ōsaka castle, the largest and most impenetrable castle in the country, on which construction had begun two years earlier. By now it was abundantly obvious to all that the Oda were out of the picture; Hideyoshi was the main man. When you consider the fact he began his life as the son of a no-name farmer/foot soldier, it’s extremely impressive how far up the ladder he’d managed to climb. Nevertheless, his weak bloodline hindered his chances of ever becoming shōgun. While it wasn’t a hard-and-fast rule that the shōgun had to have descended from the Minamoto, at the very least, it was expected that he hailed from a family of high standing. And so with virtually no chance of being able to climb the samurai ladder any further, Hideyoshi took a different route: the court.

Through a number of carefully selected targets, bribes and threats, Hideyoshi managed to have himself adopted into a branch of the Fujiwara family and be awarded the title of kanpaku along with the ‘Toyotomi’ kabane. This allowed him to create a hybrid-government that incorporated elements of both the court and the shōgunate. As kanpaku, he had the ability to award his men high-ranking positions within the court. Naturally, none of the samurai he awarded these positions to actually carried out the duties associated with the roles. This contributed further to the stagnation of the court, which by this time was nothing more than a set of rituals and ceremonies being carried out for the sake of tradition. Hideyoshi used the titles simply to denote rank within his new government. The actual roles he delegated to each of his men had nothing to do with their ‘court-awarded’ positions.

Dealing with the opposition

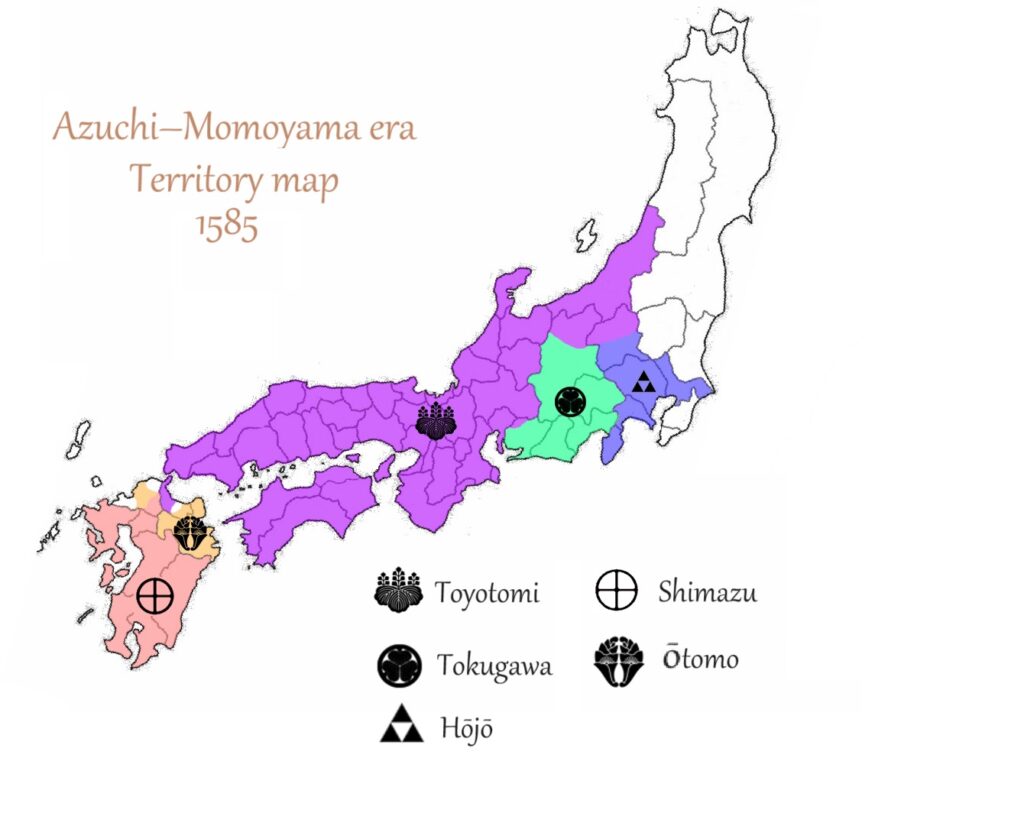

With his political situation secure and his most prominent enemies destroyed, Hideyoshi was finally free to continue his predecessor’s work of taking over the country. The previous year, during his little squabble with Tokugawa Ieyasu, a number of factions had picked the wrong side. Among the more powerful of them were the Neguroji and Kongōbuji temple complexes and the Chōsokabe clan, which ruled most of the land covering the four provinces in the large southern island of Shikoku. Hideyoshi employed diplomacy to get Kongōbuji back on side, burned down Neguroji, and invaded Shikoku, forcing a surrender from Chōsokabe Motochika. In addition to the regions of the country directly under his control, he was now allied with Uesugi, Tokugawa, Mōri and Chōsokabe. The only major powers remaining were Date in the north, Hōjō in the east and two clans vying for control of Kyūshū in the south-west.

The Kyūshū campaign

In 1586, the Shimazu―the leading power in Kyūshū―began a campaign to annihilate the already weakened Ōtomo clan. Working their way north, they succeeded in taking over more than half of the massive island. Unable to stop the Shimazu’s advance, the leader of the Ōtomo clan ran crying to Hideyoshi for help. This was the excuse the kanpaku needed to invade the region. Late in the year, he led two armies down south to the Shimazu’s territory, one led by himself and the other by his brother, Hidenaga. Seven months of fighting later, he forced the Shimazu to surrender and took control of Kyūshū.

The Siege of Odawara

In 1590, Hideyoshi found a similar excuse to attack the Hōjō. They wouldn’t be so easy to take down though; Odawara castle, their main stronghold, was an impenetrable fortress the size of a small town. In the past, Uesugi Kenshin had tried to attack it with an army of 100,000, but to no avail. To be fair though, in Kenshin’s case, the Hōjō had allies bordering his land who were willing to attack him in order to force him to give up his campaign. Hideyoshi didn’t have that problem; the Hōjō were isolated now. In addition, Hideyoshi’s army stood a little over 200,000 strong. Even with all these advantages, though, it still wouldn’t be a walk in the park.

The kanpaku spent months laying siege to Odawara while his vast army spread out around the Hōjō’s numerous territories across the Kantō plain, taking down their castles one by one. With the Hōjō distracted, Hideyoshi set up a new base of operations in a small mountain overlooking Odawara, and set to work constructing a castle in secret. Seven months later when construction was complete, he had his men cut down the surrounding trees during the night, revealing the new structure. When the Hōjō awoke the next morning, their eyes were met with the sight of a castle which, to them, appeared to have been constructed overnight. The majority of their support castles having fallen and their resources dwindling, they were already close to surrendering. Their only hope was that the enemy’s supplies were dwindling even faster than theirs. But seeing that the kanpaku still had the resources and energy to construct an entirely new castle robbed them of the last of their hope. Hōjō Ujimasa’s son, Ujinao, gave himself up, condemning himself to retirement and exile. His father was executed along with one of his uncles and a number of the Hōjō army’s top generals.

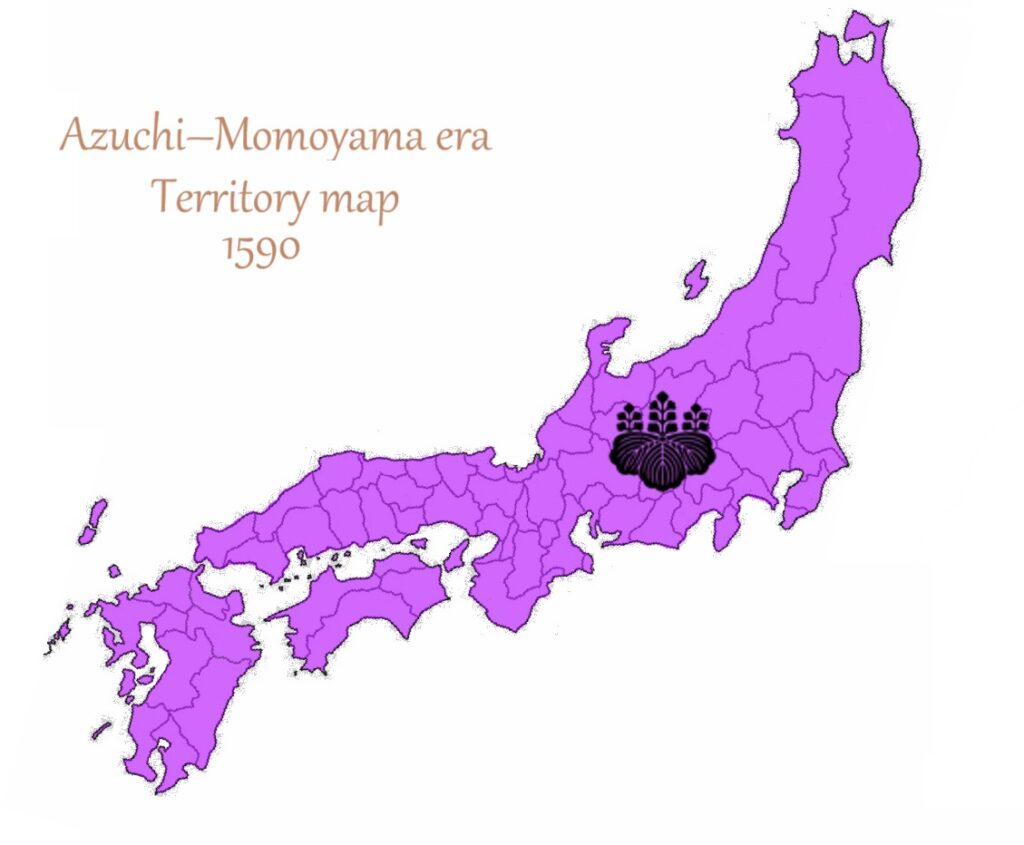

Ruler of Japan

The biggest remaining power in the east had fallen. In addition, in the middle of the Odawara campaign, the Date cowed to Hideyoshi’s pressure and led an army down south to assist him. In effect, Hideyoshi now had control over the entire country―a feat no one had been able to achieve up until that point in all Japan’s history. He awarded Ieyasu all territory taken from the Hōjō and moved his men into the former Tokugawa territory. This effectively doubled Ieyasu’s total amount of land. On the surface, it appeared to be a promotion, but some argue that Hideyoshi’s decision was based on the fact he feared Ieyasu and merely wanted to move him as far from Ōsaka as possible. This is evidenced by the fact he positioned his closest men in the areas directly bordered with Ieyasu’s new territory, allowing him to keep check on his greatest potential rival at all times.

Producing an heir

Hideyoshi had taken over the country. He was now the most powerful man among both the samurai and the court. However, he was plagued with one problem that threatened to destroy everything he had accomplished: he couldn’t produce an heir. Famously, Hideyoshi was a womaniser and had openly cheated on his wife with a multitude of women throughout their twenty or so years of marriage. Since taking over Nobunaga’s empire in 1582, his compulsions had only become worse, with him taking numerous concubines in addition to a plethora of one-off affairs with any woman who took his fancy. But despite having had relations with so many women, he had never been able to produce a child. (There are documents that state Hideyoshi had two children who died young, but these are difficult to verify. Even if their contents were found to be true, they don’t explicitly state that the infants were Hideyoshi’s biological children.)

The situation took a dramatic turn in 1588 when Hideyoshi took Cha Cha, the daughter of Azai Nagamasa and Nobunaga’s sister, as his new concubine. Being 32 years the kanpaku’s junior, Cha Cha was young, healthy and fertile. She gave birth to a son the following year. Due to the fact Hideyoshi was presumed to have been infertile, many historians doubt that he was the child’s father; in fact, many doubted this even at the time.

These speculations became academic when the child died two years later, just months after the death of Hideyoshi’s brother, Hidenaga. The kanpaku’s subsequent mental decline is attributed to these two deaths. He was already 54 years old, which, for the time, was pretty close to the average life expectancy. With little hope of being able to produce another heir, he adopted his nephew, Hidetsugu, and had him take over the position of kanpaku. With his succession solidified, he accepted the title of taikō, set to work constructing Fushimi castle in an area of Kyōto known as Momoyama(from where we get the second half of the era’s name) and made arrangements to retire there upon its completion.

The first Korean invasion

While all this was going on, Hideyoshi decided to invade Joseon―the dynasty that ruled the Korean peninsula. The reason for this is largely unclear. With 120 years of fighting finally having been brought to an end, nobody wanted to have to start a new war for no good reason. So why did the taikō make this decision? Some say the plan had originally been devised by Nobunaga, and Hideyoshi was simply following through with it. Some say he needed new land to be able to offer the vast army of samurai he now had under his command. Others say he was simply going senile. Whatever the case, he started a war in which no one was interested in participating. While his men were away fighting this war for him, he received some unexpected news: Cha Cha was pregnant again.

Hidetsugu

In August of 1593, Hideyoshi realised the Joseon campaign was failing. He called his men back and went about arranging a peace treaty. That same month, Cha Cha gave birth to a son, Hideyori. This spelled problems for Hidetsugu. Hideyoshi asked his nephew to continue the role of kanpaku until Hideyori came of age, but over the coming months, his attitude towards Hidetsugu began to change. Without making it clear where his nephew stood, Hidetsugu became increasingly paranoid. This led to miscommunication between the two, which escalated to the point where Hidetsugu was refused a meeting with his uncle and was ordered to put himself under house arrest in Mount Kōya. While awaiting his next orders, He killed himself.

There are conflicting theories regarding Hidetsugu’s death. Some state he did it of his own accord. Others state he was ordered to do it. Whatever the case, Hideyoshi followed up by ordering the deaths of Hidetsugu’s wives, concubines and children―39 people in total. He even ordered the death of a 15-year-old girl whose father Hidetsugu had convinced to allow him to marry. She had never once met with Hidetsugu at the time of her execution, but despite the many protests of his advisors, Hideyoshi was insistent upon her penalty. This is one of the many pieces of evidence presented as the case for the taikō’s senility.

The second Korean invasion

In 1597, the ongoing negotiations that had been continuing with Joseon for the past four years broke down. Hideyoshi decided to have a second go at invading the peninsula. Once again, samurai from all over the country reluctantly crossed the Japan Sea to fight long and arduous battles. This time, however, one year in, the war came to an abrupt end… due to the death of Hideyoshi! His closest retainers did all they could to bring the men back as quickly as possible without letting word slip to Joseon that their leader had kicked the bucket. However, shocked as the samurai community was upon learning of the death of the country’s most powerful warlord, unlike the events following Nobunaga’s death, there was no mass panic. Fully aware of his impending demise, Hideyoshi had put measures in place to ensure his family would be safe and secure in their position until his son came of age. He established two teams: one consisting of five elders―five of the most powerful daimyō in the country―and one consisting of his top five magistrates.

The five elders and the five magistrates

The Five Elders

- Tokugawa Ieyasu

- Mōri Terumoto

- Maeda Toshiie

- Ukita Hideie

- Kobayakawa Takakage

- Uesugi Kagekatsu(brought in after the death of Kobayakawa Takakage)

The Five Magistrates

- Ishida Mitsunari

- Maeda Geni

- Asano Nagamasa

- Mashita Nagamori

- Natsuka Masaie

Each group was given a very specific set of rules to follow, but not all members were able to stick to those rules; Ieyasu began marrying his children to members of powerful daimyō families―an act that was strictly forbidden in samurai society even before Hideyoshi’s death. Ieyasu’s charisma coupled with the fact he’d performed a number of favours for a number of young daimyō over the years allowed him to get away with this. One man wasn’t willing to drop the matter, though: Ishida Mitsunari. The two began to butt heads.

Luckily for Ieyasu, Mitsunari had made a number of enemies among the young samurai who had been sent over to Joseon. Having been put in charge of the administrative aspects of the war, he had been forced to make some very unpopular decisions. To make matters worse, when all the men were finally brought back home, Mitsunari was the one who had to tell them that there were no rewards to dish out for all their hard work. In fact, the only person who had the power to hold them back from attacking Mitsunari was Maeda Toshiie, who had formed close relationships with and even mentored some of the young samurai over the years. In early 1599, however, Toshiie suddenly died. All bets were off.

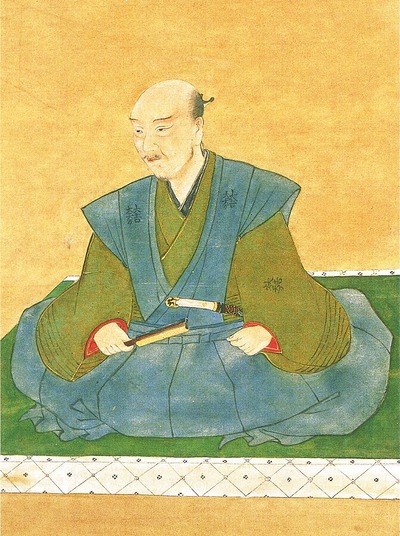

Tokugawa Ieyasu

Sekigahara

Seven young samurai stormed Mitsunari’s residence the day after Toshiie’s death. And who did Mitsunari escape to? Ieyasu! The leader of the elders calmed the young samurai down by agreeing to convince Mitsunari to retire. Naturally, Mitsunari saw straight through Ieyasu’s plan to get him out the way so he could continue breaking the rules and amassing even greater power, but he couldn’t deny the fact that remaining in Ōsaka was too dangerous. Reluctantly, he returned to his castle in Ōmi.

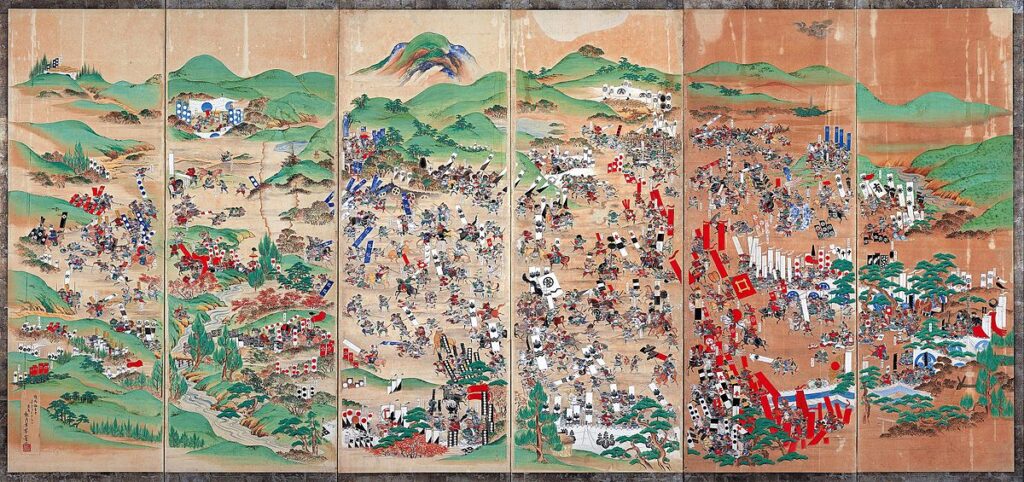

With Mitsunari out the way, Ieyasu conducted a series of strategies that removed all other troublesome elements from Ōsaka. Meanwhile, Mitsunari quietly recruited allies from the comfort of his own home. By September of 1600, both sides had amassed considerable armies. Mitsunari made the first move, attacking Fushimi castle. Ieyasu was in his home territory of Edo at the time. He gathered his army and marched it west. After taking down Fushimi, Mitsunari marched his army out east. The two sides met at Sekigahara, a large plain surrounded by mountains, where they could strategically disperse their generals. The battle lasted just six hours. Although Mitsunari’s army had the upper hand in the first half, towards the end, a great deal of side-switching occurred, which tipped the balance in Ieyasu’s favour and forced the majority of Mitsunari’s men to flee. With no one left to defend him, Mitsunari himself took off into the mountains. He was discovered six days after the battle hiding in a cave and taken captive. Two weeks later, he was beheaded.

The Edo shōgunate

To the victor go the spoils… Three years after Sekigahara, Ieyasu was awarded the title of Sei-i-taishōgun. By that time, he had already established his shōgunate in Edo―based in the Musashi province in eastern Japan―and rewarded those who fought alongside him in Sekigahara with various amounts of land. 140 years of fighting had been brought to an end; there was finally peace. Or so it seemed… Ieyasu still had one more loose end to tie up: the growing power of Toyotomi Hideyori. It was only a matter of time before Hideyoshi’s young heir became strong enough to challenge the ageing Ieyasu, who was now over 60 years of age. Many of the men who had picked his side in Sekigahara were still loyal to the Toyotomi. If Hideyori were to start a rebellion, there was a good chance that all Ieyasu had achieved could be destroyed. Doubting his own heir’s ability to be able to eliminate this threat, he needed to deal with it himself while he still had enough strength to do so.

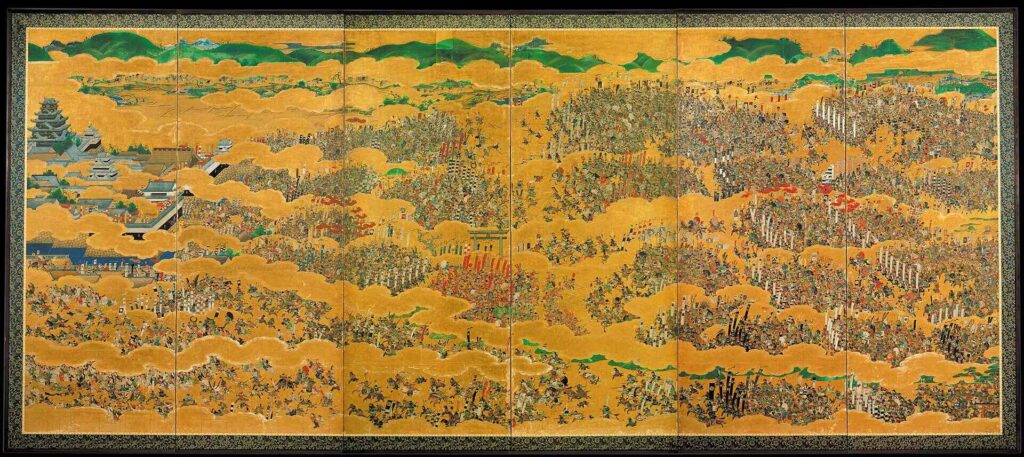

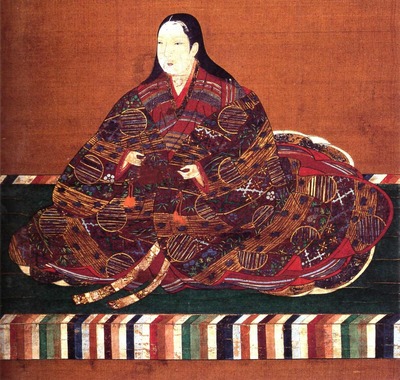

The Siege of Ōsaka

In 1614, Ieyasu found the flimsiest of excuses to allow him to thrust an ultimatum on Hideyori: leave Ōsaka, come to visit him in Edo(essentially placing himself under the rule of the shōgunate), or send his mother to live in Edo as a hostage. Hideyori’s mother, Cha Cha, who was now known as Yodo-dono, was headstrong. She had continued to refuse to acknowledge Ieyasu’s claim to the country since Sekigahara, and still believed the Toyotomi were the nation’s true rulers. She chose to fight. After mustering all the men she could, she reinforced Ōsaka castle and awaited the shōgun’s advance. The Toyotomi army was 90,000 strong―larger than almost any army that had fought throughout the entirety of the Sengoku era. However, Ieyasu had over 200,000 men at his disposal! Nevertheless, the Toyotomi army fought well, making use of its home-field advantage to fend off the shōgunate army. It all came to an end, though, when Ieyasu had the canons he had purchased from England and Holland delivered to the battle zone. One well-aimed blast penetrated the top floor of the castle, close to where Hideyori and Yodo-dono were hiding. They had no choice but to surrender.

As part of the terms of their surrender, the Toyotomi agreed to having all but the very outer of Ōsaka castle’s moats filled in. However, Ieyasu ordered his men to fill the outer moat as well, leaving the castle defenceless. He also ordered Hideyori to either get rid of his mercenary samurai army or relocate. Naturally Hideyori wasn’t willing to relocate, but it would be difficult to dispose of such a large army that had fought for his benefit, leaving them with nowhere to go. Neither Hideyori nor Yodo-dono could make a decision. Ieyasu figured this would be the case. And so the following year, while Hideyori was still mulling over his options, the shōgun led an army to Ōsaka once more to finish the Toyotomi off for good. After watching their generals fall in battle one after another, Hideyori, Yodo-dono and a handful of their most loyal men retreated to a small store room at the foot of the castle, where they took their own lives.

The battle was won and the Toyotomi threat was eliminated. Secure in the fact that nothing was left to stand in the way of the world he had created, Ieyasu died the following year. Despite the many atrocities he had committed in his quest to take over the country, he succeeded in ushering in an era of peace that would last for over 260 years. The ends justify the means. To learn about this era of peace―the Edo era―join me in part eight of this overview of Japanese history.