Oda Nobunaga – Japan’s Greatest Warlord Pt. 1

Some men need no introduction. In Japan’s case, no one man needs less of an introduction than Oda Nobunaga. I’m willing to bet more Japanese people know his name than the full name of the current prime minister. Undoubtedly the most famous samurai of all time, he ranks in the top three of virtually every samurai ranking that has been conducted in the modern age. In fact, more often than not, he’s number one with a bullet.

But is he worthy of this fame? I’m going to skip to the conclusion and say… yes! While his wasn’t the rags to riches that story that Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s turned out to be, he wasn’t born into a family that had any prospect of achieving anywhere near the level of success that he did. He put his geographical location in the country to good use, took advantage of every opportunity that presented itself and put in the work to rise through the ranks to the status of number one samurai in the country.

Face of a warrior

Before we look at the path he took to this success, let’s look at his face. While most Japanese people have an image of a furrow-browed, mustachioed, stern-faced warrior, strangely, the first image of Oda Nobunaga with which they are presented―the image in their elementary school textbook―is far from that of the powerful conqueror they hold in their heads. Let’s take a look at the textbook image first.

Hmm… A typical balding middle-aged man. This painting is somewhat lacking in energy. However, having been painted just one year after Nobunaga’s death, it is, most likely, an accurate portrayal of not only his appearance but also his character. So that being the case, what brought about the very different aforementioned image of the warlord carved into the minds of Japanese people? Most likely, the fact that dozens of the country’s top actors have portrayed Oda Nobunaga over the years caused them to form a kind of general, vague, fused image of all these actors’ faces.

A myriad of Nobunagas

We’ve seen a myriad of Nobunagas in the last few decades, from testosterone-fuelled Eguchi Yōsuke to baby-faced Sometani Shōta. Every one of them adds his own ingredient to the recipe. Toss in all the Nobunagas we’ve seen in dozens of manga, anime and game series, and the recipe becomes even more convoluted. Then there’s the fact that his accolades conjure up the image of a tall, strong, powerful brute, adding extra spice to the dish. Too many cooks have spoiled the broth that is Oda Nobunaga. Considering the myriad of ‘ingredients’ that went into creating Japan’s favourite historical character, is it now even possible to reverse-engineer the recipe and figure out what he actually looked like?

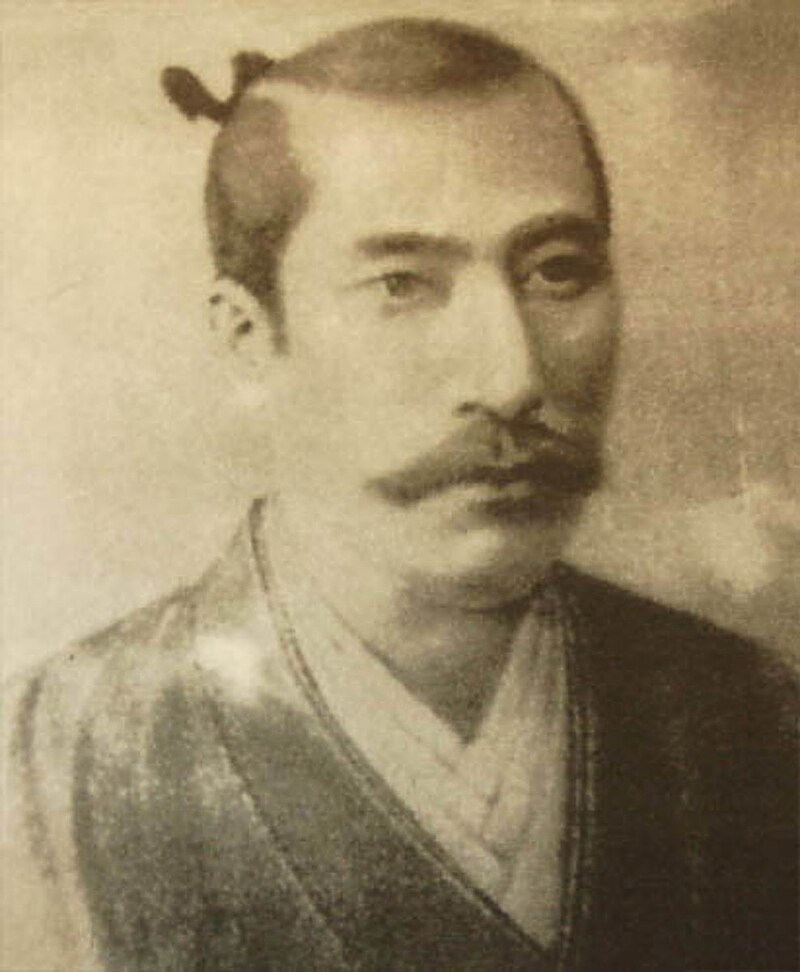

Luckily, we don’t have to; unlike the majority of Sengoku era samurai, whose faces may forever remain a mystery, Oda Nobunaga’s portrait was painted by an Italian artist named Giovanni Nicolao. Unfortunately, as Nicolao arrived in Japan shortly after Nobunaga’s death, he only had existing paintings and descriptions from Nobunaga’s closest aides on which to base his work. Let’s put authenticity aside for a moment, though, and take a look…

Okay! This is a much clearer image! Put it side by side with the textbook image and you can see the similarities. Is it accurate? Who knows? But it’s probably the closest we’re ever going to get. So, keeping this image in our minds, let’s take a look at the life of Japan’s greatest warlord.

Refer to the above map to view the locations of the various castles mentioned in this article

Early life

Oda Nobunaga was born in 1534 to Oda Nobuhide and Toda-gozen in a small region of central Japan known as Owari. His childhood name was Kippōshi. He had an older brother, Nobuhiro, born to one of Nobuhide’s concubines. Despite being his second son, as his first true-born son, Nobuhide regarded Nobunaga as his heir from the moment he was born and went so far as to award him Nagoya Castle before he had even reached adulthood.

Nobunaga also had a younger brother, Nobuyuki, born of the same mother. To Nobuyuki, Nobuhide awarded Suemori Castle. Even though Nobuhide had already named Nobunaga his successor, Nobuyuki began to amass a great amount of support from the clan’s retainers early in his childhood, chiefly due to the fact that Nobunaga was seen as an idiot in the eyes of many. He dressed in brightly-coloured sleeveless attire which, at the the time, was normally used as a bathrobe. He munched on chestnuts, persimmons and gourds while strutting through the streets with a small band of private soldiers in tow. At his father’s funeral, he threw incense onto the memorial tablet.

All these incidents are listed in the Shinchō-kōki, a series of books written during the time Oda Nobunaga was alive, focusing on his life and achievements. Compiled by Ōta Gyūichi―a samurai who worked close to Nobunaga from an early age―historians regard it as having a relatively high degree of authenticity. However, historians also agree that since Nobunaga didn’t display any of these unusual qualities after establishing himself as a major contender among the Samurai community, it’s likely that his dimwitted attitude and behaviour were simply a performance to lull his potential enemies into a false sense of security.

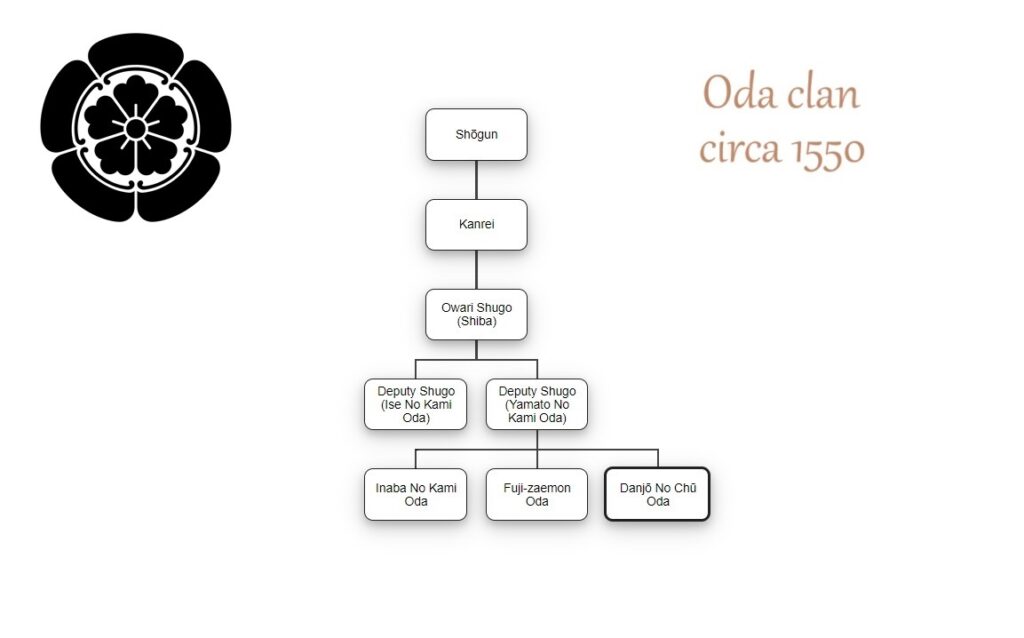

The Oda clan

Before we get into the sibling rivalry, let’s check out at the Oda family’s status and find out where they fit into the samurai hierarchy. If you look at the diagram above, you’ll see the shōgun at the top. Assuming he needs no explanation, let’s skip him and go one notch down to the kanrei. Effectively the shōgun’s right-hand man, the kanrei was chosen from one of three families: Hatakeyama, Hosokawa and Shiba. You’ll notice the Shiba family also happened to be Owari’s shugo. For every shugo, there is a deputy shugo―a secondary family who governed the region while the shugo was away in the capital.

Owari was in the unique position of having not one but two deputies. During the Ōnin war of 1467, the Oda clan split into two factions, the Ise no kami Oda and the Yamato no kami Oda, and took opposing sides. Each faction was named after its leader’s court-awarded role. The Ise no kami branch controlled four districts to the north of Owari and made Kiyosu Castle its base of operations. The Yamato no kami branch controlled four districts to the south and was based in Iwakura Castle. Three sub-branches supported them: Inaba no kami, Fuji-zaemon and Danjō no Chū. Oda Nobunaga belonged to the Danjō no Chū branch.

To sum up, Nobunaga belonged to the sub-branch family of one branch of the deputy shugo, who worked under the shugo, who worked under the kanrei, who reported to the shōgun. While not a million miles from the top, born into a status like this, it was unlikely that Nobunaga would have any hope of ruling Owari let alone the capital. So how did he do it? Before we look into that, let’s return to his early years and fill in a few gaps.

The Saitō

To the south of Owari was the ocean. To the west lay Ise, which didn’t pose much of a threat. The north and the east were the problem. Mino, in the north, was under the control of the Saitō clan. The three regions to the east belonged to the Imagawa, one of the most powerful feudal clans in the country. They were looking to create a path to the capital, and Owari was in their way.

Nobuhide spent years fighting both clans before deciding it was time to form an alliance and reduce the strain on his army. He struck a deal with Saitō Dōsan and agreed to have Nobunaga marry his daughter, Nōhime. Nobunaga was just 14 at the time. Nōhime was 13. Dōsan decided to meet with Nobunaga at a temple called Shōtokuji to determine whether he really was as moronic as everyone said he was. His jaw dropped when Nobunaga appeared on the scene leading a large infantry of soldiers, all sporting Tanegashima rifles. The Shinchō-kōki quotes Dōsan as saying that upon speaking with his new son-in-law, he knew for certain one day his own sons would be working under him.

Despite the relationship formed between Oda Nobunaga and Dōsan however, Nobunaga and Nōhime never had any children together. Whether this is because the two didn’t get on or because Nōhime couldn’t bear children is unknown. In fact, history records very little about Nōhime at all. After marrying Nobunaga, she falls into obscurity. No one is sure how or when she died. Nobunaga’s real love was a concubine named Ikoma Kitsuno, who bore his three eldest children. Unfortunately, the two didn’t have long together as she died in 1566, just ten years after they first met. History books record very little about Nobunaga’s other concubines.

Establishing a power base

Let’s return to Oda Nobunaga’s status for a while. As I mentioned before, Nobunaga’s branch of the Oda family was located far down the hierarchy. However, all was not as it seemed; officially, the Danjō no Chū branch served the Yamato no kami Oda, but in reality, Nobuhide had built up a far greater power base than his masters. His father, Nobusada, had spent most of his early years developing a port town to the west of Owari, known as Tsushima. This allowed him to engage in trade with western Japan, which helped him amass a small fortune for his branch of the family. He built Shobata Castle―where Nobunaga is assumed to have been born―and passed his legacy on to his son.

Nobuhide continued his father’s work by acquiring an area known as Atsuta and developing it into the family’s second economic base. He built two more castles, Furuwatari and Suemori, and stole Nagoya Castle from the Imagawa. With two towns and four castles under their belt, by the time Nobunaga was born, the Danjō no Chū branch was already far richer and more powerful than the Yamato no kami Oda.

The Shiba

The Shiba clan wasn’t doing too well either; in 1515, its leader, Shiba Yoshitatsu, ignored the advice of virtually his entire council and led an army east to take on the Imagawa. Just as his advisors had predicted, the battle was over pretty much before it had even started. Yoshitatsu was taken prisoner, shaved bald(effectively implying that he was to enter the priesthood) and sent back to Owari. Upon his return, having been left with practically no choice but to retire, he passed control of the Shiba clan to his three-year-old son, Yoshimune. Naturally, as Yoshimune was far too young to run the clan, he relied on the support of the Oda, allowing them to gradually usurp power from their shugo masters.

In 1554, Oda Nobutomo, head of the Yamato no kami branch of the Oda clan, attacked Shiba Yoshimune’s residence and forced him to kill himself, under the suspicion that he was in cahoots with Oda Nobunaga. Yoshimune’s younger son, Yoshikane, was out hunting at the time with the bulk of his father’s army. With defences low at the Shiba family’s residence, Nobutomo had picked the perfect time to strike. Upon hearing the news of his father’s death, Yoshikane ran to Nagoya Castle and begged Nobunaga for help. With the shugo’s son under his protection, Nobunaga had the perfect excuse to launch a campaign against Yamato no kami. One year and a couple of battles later, he’d weakened his rival to the point he was able to storm Kiyosu Castle and kill Nobutomo. The Yamato no kami branch of the Oda family was no more.

Sibling rivalry

With Kiyosu Castle under his belt and the main branch of his family eliminated, only Ise no kami stood in the way of Oda Nobunaga controlling all of Owari. Just one more step until his home region was all his. Or so he thought… A new challenger was about to enter the arena. Yes! We finally return to Nobunaga’s younger brother, Nobuyuki. Due to the fact that Nobunaga was considered a moron by a large faction of the Oda clan―and also possibly because he was against taking action to create peace with the Imagawa, as his father had been considering before his death―the clan’s support was split between the two brothers.

It all came to a head in 1556 when the two met on the battlefield. Nobuyuki’s army outnumbered Nobunaga’s by a thousand, but, perhaps due to the fact that Nobunaga personally led his army to battle, his men were motivated enough to drive their enemy back to their base. If not for his mother’s intervention, Nobunaga would have most likely laid siege to Suemori Castle until his brother killed himself.

A period of peace followed, which lasted for two years before Nobuyuki decided it was time to challenge his brother once more. This time, however, one of his closest retainers, Shibata Katsuie, gave the game away, informing Nobunaga of his brother’s intended mutiny. Nobunaga feigned sickness and lured Nobuyuki to Kiyosu Castle, where he had him killed. Having now eliminated his most immediate threat, he was free to turn his attention back to the Ise no kami branch of the Oda clan.

Conquering Owari

As luck would have it, that same year, Oda Nobukata, son of the head of the Ise no kami branch, exiled his father and took over Iwakura Castle. There was no way Oda Nobunaga wasn’t going to take advantage of an opportunity like this! He quickly married one of his sisters to Oda Nobikiyo―ruler of Inuyama Castle and retainer of the Ise no kami branch. Together, they defeated Nobukata in battle. One year later, they laid siege to Iwakura Castle and forced Nobukata to surrender on the condition of his exile. This put Nobunaga and Nobukiyo in control of the entire region of Owari. Naturally, though, the two ended up arguing over the division of land. Nobunaga succeeded in driving Nobikiyo out of Owari in 1664, awarding him complete and undisputed control over his homeland.

Imagawa Yoshimoto

Before we move on and learn how Oda Nobunaga expanded his new empire, let’s first go back a few years, because we’ve skipped over a crucially important event―perhaps the most defining event of Nobunaga’s career: Okehazama. In the 1550s, Imagawa Yoshimoto succeeded in taking over two of Nobunaga’s castles: Narumi and Ōdaka. Rather than try to retrieve them, Nobunaga surrounded the castles with five fortresses to keep them in check and, possibly, to eventually lure Yoshimoto towards him. Whether the latter was a part of his plan or not is unknown, but if it was, Yoshimoto took the bait; in 1560, the renowned leader of the Imagawa led an army of 25,000 west to take down the fortresses.

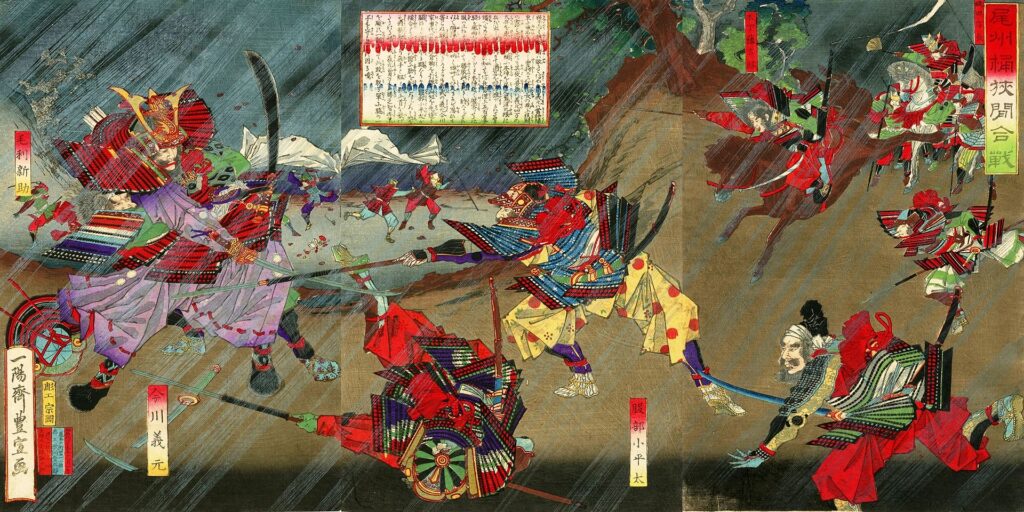

The Battle of Okehazama

Upon hearing word of Yoshimoto’s expedition, Oda Nobunaga sent out scouts to determine the location of the Imagawa army’s camp. They pinpointed the location to an area called Okehazama. Before any of the spies Yoshimoto undoubtedly had scattered among the Oda army’s soldiers could spread word of his plan, Nobunaga gathered 2,000 or so men and led them among a narrow, secluded route, far from Imagawa eyes, advancing slowly towards Okehazama.

Luck was on his side: a heavy rain began to pour as he neared the enemy base, masking the sound of his army’s approach. Yoshimoto had 6,000 or so men stationed at the camp. As the rain began to die down, the Oda army charged, taking the unprepared Imagawa army by storm and spreading mass confusion. By the time Yoshimoto realised what was happening, several of Nobunaga’s men had already reached his location. One swing of a sword and the leader of the infamous Imagawa clan fell dead. Oda Nobunaga had done the impossible; despite having been outnumbered 10:1, he had taken down one of the biggest samurai clans in the country. Everything he had undertaken up till that point had been little more than a family feud in the eyes of the samurai community. Now, he finally had their attention!

On that note, we’re going to take a break. Join me in part two to find out what happens once Oda Nobunaga leaves Owari and forges a path to the capital in a bid to become a major contender for ruler of Japan.