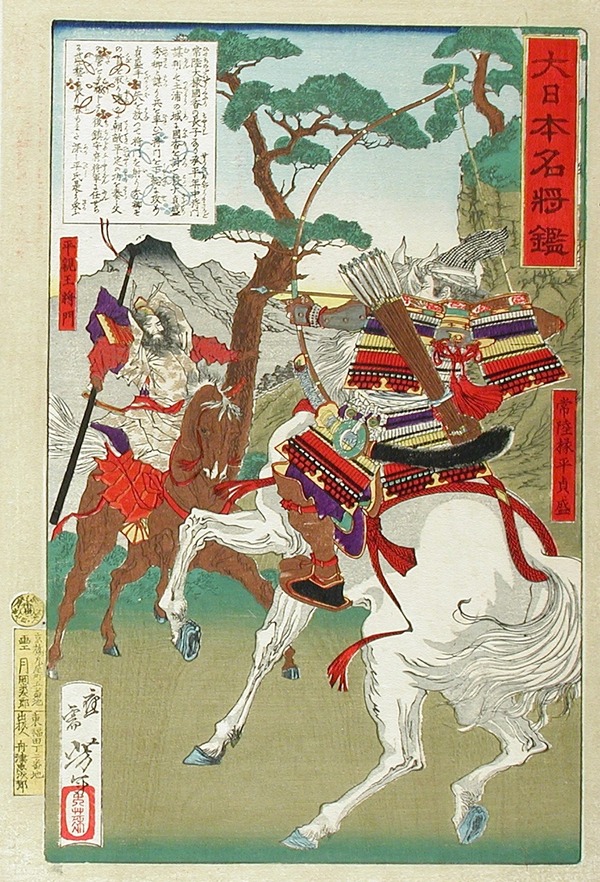

Taira no Masakado – The first samurai

When it comes to samurai, I love extremes. The first, the last, the strongest, the weakest, the kindest, the cruelest… I plan to do them all eventually. But today… the first! The very beginning of samurai culture: Taira no Masakado. Of course, he isn’t actually the first samurai. No one knows who the real first samurai was, nor can anyone pinpoint the moment in time when farmers protecting their land from court-appointed officials developed into an organised warrior society. Masakado is more than worthy of the title though; not only is he the first samurai to have received significant documentation in Japanese history, but he is also the first to have posed a significant threat to the court and paved the path for over 600 years of samurai domination.

Unfortunately, as the main historical text that documents Masakado’s accolades is a war chronicle, a lot of the information we have about him needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. Exaggerations are rampant and fantasy elements have been woven into his story for dramatic effect. While it is an interesting read, it’s a bit like trying to learn about the Spartans by watching ‘The 300’. With that disclaimer in place, let’s take a look at the life of the pioneer who encouraged and inspired generations of samurai to come.

The Taira

Taira no Masakado hails from the infamous Taira clan, who would eventually rise to the top of samurai society and fight an infamous five-year war against the Minamoto clan for control of Japan. Both the Taira and Minamoto are descended from the Imperial Family. Early in the Heian era, when an emperor had too many children for the court to be able to support them all financially, he would ‘relegate’ a number of his princes by granting them a kabane and awarding them jurisdiction over areas of the country not yet under the direct control of the court.

In the short run, this was good for the court as it not only allowed them to cut down on child-support expenses but also allowed them to maintain a stronger grip on rural regions of the country far from the capital. In the long run, however, it would prove to be a terrible decision: rural farmers with no connection to the court other than their hatred for the officials sent to their land to extort exuberant amounts of tax from them would band together under these famous formerly-royal figures to form small armies that would quickly become more powerful than that of the court. Taira no Masakado was the first to take advantage of this situation.

Family history

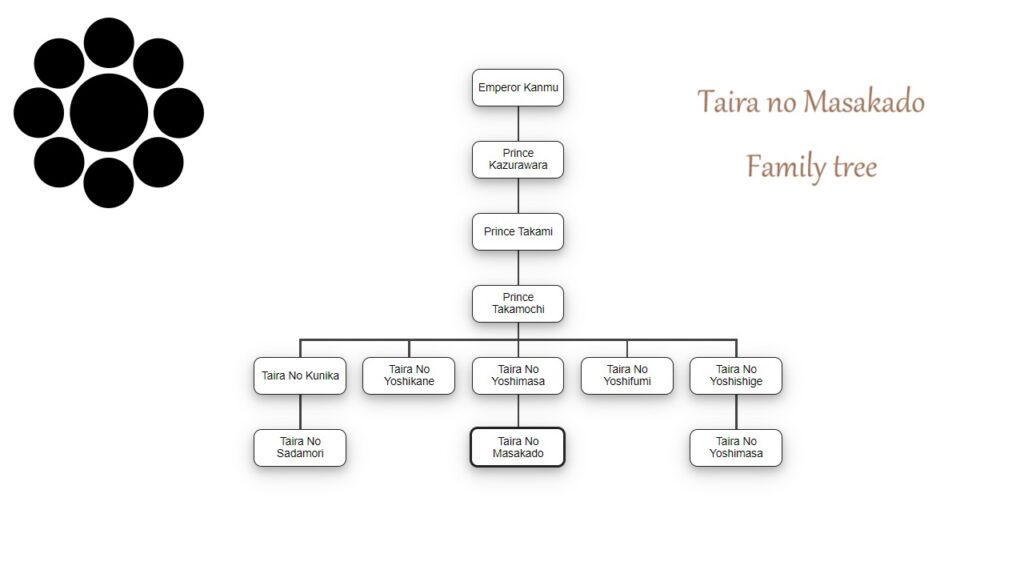

In 889, Masakado’s grandfather, Prince Takamochi was granted the Taira kabane. The name ‘Taira’(平) most likely originates from the name of the capital: Heian-kyō(平安京), suggesting that the court didn’t intend to cut all ties with Takamochi. He was later awarded land in the province of Kazusa, east of the capital, and sent there to try to get the area under the court’s control. Takamochi’s sons, Kunika, Yoshikane, Yoshimasa, Yoshifumi and Yoshishige (don’t worry. You don’t have to remember all these. They’re fairly minor characters in the overall story), branched out and expanded their father’s influence across the Kantō plain. Yoshimasa settled in Shimōsa and married, producing a number of sons, the oldest of whom was Masakado.

Early life

In 918, at the age of 15, Masakado was sent to the capital to become an attendant of Fujiwara no Tadahira, head of the Fujiwara family and the emperor’s right-hand man. During his time in the capital, he trained to become a kebiishi, but due to his father’s status(or lack thereof), he was only able to join the Takiguchi no bushi. 12 years later, upon receiving news of his father’s death, he returned home to Shimōsa.

Family feud

Upon his return, he discovered that three of his uncles had taken over his father’s land and married the daughters of Minamoto no Mamoru, an influential landowner in Kantō. Thus began the Taira’s epic family feud.

Kunichika attacked first, but Masakado escaped with the aid of the one uncle who chose to remain on his side: Yoshifumi. Mamoru’s three sons followed up the attack, but Masakado succeeded in driving them back to their land, where he killed them and burned down their villages. Before his momentum had a chance to die down, he invaded Kunika’s territory and killed him too, removing a great deal of the threat to his land in the space of a couple of small battles.

Needless to say, Mamoru wasn’t about to let his sons’ deaths go unavenged. He approached Yoshishige’s son, Yoshimasa(the same name as Masakado’s father, but the Chinese characters are different), and convinced him to join the battle. Before the two could formulate a plan, however, Masakado made a preemptive strike and defeated Mamoru.

Yoshimasa travelled to Hitachi and raised an army, which he advanced on Masakado, but he too was swiftly defeated. After being forced back, Yoshimasa appealed to Yoshikane to join the cause. Yoshikane agreed and succeeded in getting Kunika’s son, Sadamori, on side.

The combined force of Yoshimasa, Yoshikane and Sadamori’s armies bore down on Masakado, but, unbelievably, even this wasn’t enough to take him down! Masakado defeated all three men and forced them to flee and take refuge in Shimōsa’s provincial offices. Not only was Masakado able to fend off the three armies, but he was even able to send his men after them and surround the offices, leaving them no room to escape.

It’s events like these that force you to raise an eyebrow and question the extent to which the story’s been embellished, but since there’s no way to verify the details, I feel it’s better to accept it as gospel and immerse yourself in the epic tale. Also, as I mentioned before, don’t worry about remembering names or events at this point. Only a handful of them have any historical significance.

Court summons

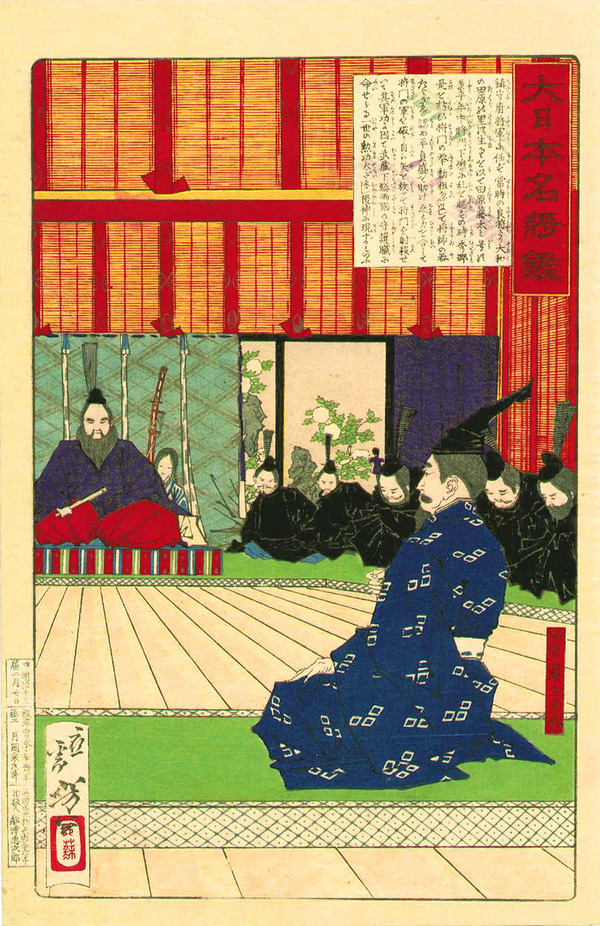

Returning to the story, somehow Yoshikane managed to find a gap in the blockade and escape the siege. Masakado explained the situation to the court-appointed officials inside the offices and marched his men back home. By this point, pretty much everyone involved had realised that Masakado couldn’t be defeated by force, so Mamoru decided to take a different approach: he travelled to the capital and went crying to the court, who sent a messenger to Masakado demanding he come and tell his side of the story. Considering the fact that Masakado had returned to his homeland expecting to rule in peace, only to find himself being attacked constantly from all angles for no good reason, he was most likely extremely reluctant to have to travel halfway across the country just to defend himself. Nevertheless, he made the journey, gave his side of the story and ended up being detained for two years until Emperor Susaku took the throne, at which point a number of people, including Masakado, had their ‘crimes’ pardoned.

The moment he returned to Shimōsa, Yoshikane resumed his attack. No rest for the wicked; history really forced Masakado to earn his place in its books! However, this time, Yoshikane made a huge blunder: he joined up with Sadamori to burn down a number of court-owned stables that were under Masakado’s jurisdiction. Needless to say, the court wasn’t happy about this. Masakado leveraged this fact to obtain permission from his former mentor, Tadahira, to take down his uncle and cousin for good. Having the court on his side was a great morale boost for his army, and it encouraged a greater number of men to join his ranks. With his new and improved forces, he drove off both Yoshikane and Sadamori and finally managed to convince them to leave him alone once and for all. Sadamori fled to the capital; Yoshikane died of illness two years later.

Prince Okiyo and Minamoto no Tsunemoto

After defeating his uncles and cousins, Masakado had complete control over the greater part of Shimōsa, Kazusa and Hitachi. He was supposedly a much better ruler than his uncles, intervening in land disputes that arose and helping to resolve them peacefully. Despite the fact that he had spent much of the previous three years fighting constant battles in order to defend his territory, he was really an advocate of peace who tried to avoid conflict wherever possible.

In 938, he mediated a dispute among Prince Okiyo, the provincial governor of Musashi; Musashi Takeshiba, the district governor of Adachi; and Minamoto no Tsunemoto. Masakado had the two governors meet to discuss the situation, but Takeshiba’s men suddenly surrounded Tsunemoto’s army, which was standing guard outside the meeting’s venue. Tsunemoto managed to escape and flee to the capital to report the situation to the court(the go-to move of any samurai backed into a corner). Despite being allied with Okiyo and having no beef whatsoever with Masakado, for some reason, Tsunemoto decided to betray all three men and claim to the court that they were planning a rebellion. Tadahira sent a messenger to Masakado demanding an explanation, but Masakado used his fame and popularity in the region to get five provincial governors to vouch for him. With that many sponsors and the fact that Tadahira knew Masakado better than perhaps anyone, Tadahira had no reason to doubt his former protégé. And so he locked up Tsunemoto, putting an end to the affair.

Rebellion

In 939, a man by the name of Fujiwara no Haruaki sought help from Masakado after Hitachi’s provincial governor put a bounty on his head for non-payment of taxes and stealing from the official rice storage supplies. To be fair, he’d only stolen the rice to distribute it to impoverished farmers. Fully aware of this fact, Masakado marched 1,000 men to the provincial offices and demanded that the arrest warrant be repealed. Naturally, the offices refused. The battle commenced. Masakado easily took down the governor’s 3,000 men, burned down the offices and stole the official court-appointed seal, effectively giving him control over the entire province of Hitachi.

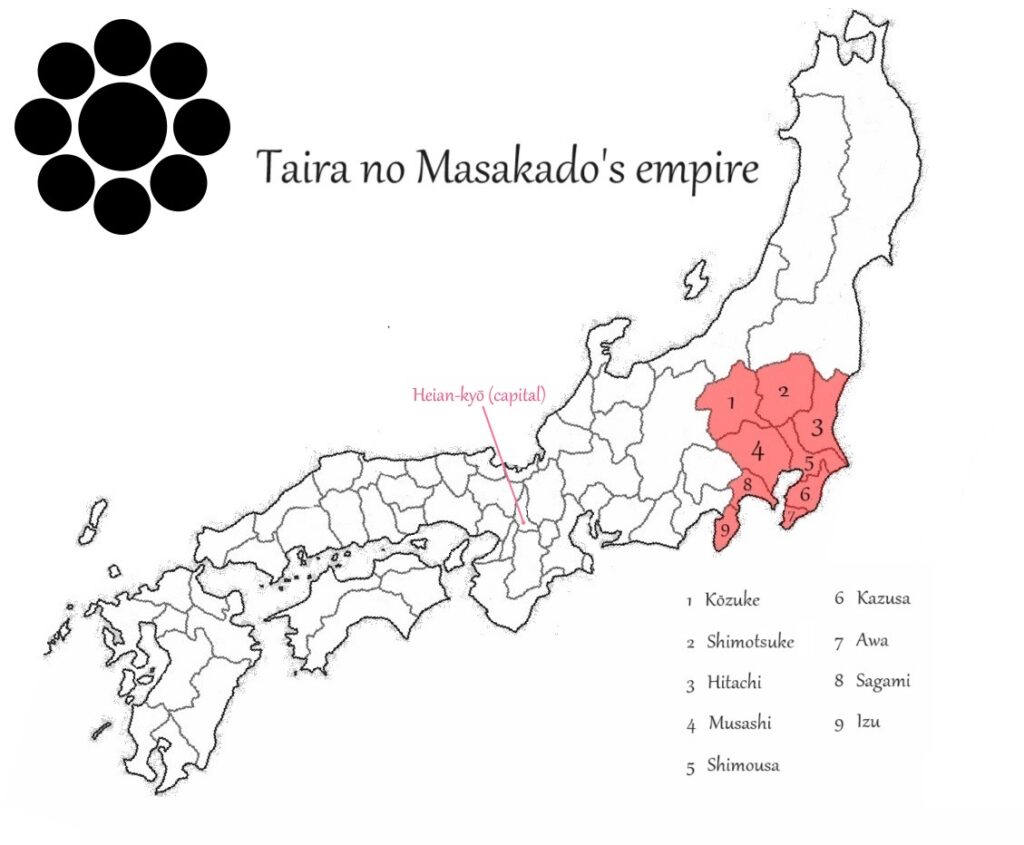

There was no going back now. Every battle he had been involved in up until that point had been nothing more than a family feud in the eyes of the court. This, on the other hand, was rebellion. Prince Okiyo advised Masakado that it was in his best interest to continue the rebellion and take over the entire Kantō plain. After all, the court was never going to forgive him. Rather than try to defend against the impending Imperial Army, the safer option was to expand his influence to the furthest reaches of Kantō. In for a penny, in for a pound. Masakado attacked Shimotsuke, forced the governor to surrender and hand over the official seal, then drove him out from the land. Several days later, he repeated the process with Kōzuke. Before he knew it, he had control over the entire eastern plain of Japan.

The New Emperor

One day, a priestess came to Masakado and informed him that the spirit of Sugawara no Michizane had entered his body. Michizane was a court noble who died in the early 10th century, shortly after being demoted and sent to Dazaifu in the far west of Japan. In the thirty years following his death, a number of disasters and untimely deaths occurred, leading the court to believe that Michizane’s spirit was angry(clearly they were still feeling some residual guilt over how they’d treated him while he was alive). Masakado’s rebellion came at a time when the memory of Michizane and fear of his curse were still fresh in the minds of the people. For this reason, the priestess’ words held a great deal of weight. She proclaimed Masakado the ‘New Emperor’. This prophecy served to gain him further support and help him amass an even larger army, solidifying his position as ruler of the east.

Ruler of the east

Masakado set to work governing his new realm, assigning the roles of provincial governors to his brothers and closest followers. As the only uncle not to have opposed him, he allowed Yoshifumi to retain control of Musashi. Needless to say, these actions displeased the court greatly. The first step they took was to have their top priests pray for Masakado to be cursed, but that didn’t work(obviously). Unfortunately, though, they didn’t have many other options; by pure coincidence, a man by the name of Fujiwara no Sumitomo had started a similar rebellion in the west, and the Imperial Army was busy trying to put a stop to him. With few men left to spare, the court sent a high-ranking official, Fujiwara no Tadafumi, to take care of the Masakado situation, while also sending messengers to the east to try to rally local families and get them on side with promises of wealth and status. A man by the name of Fujiwara no Hidesato took the court up on their offer and went to seek out Taira no Sadamori to see if he was up for taking on his uncle one last time.

As a side note, in case you were wondering what happened to Minamoto no Tsunemoto, he was forgiven by the court and released when his claim that Masakado was starting a rebellion turned out to be true(even though it wasn’t true at the time he made the claim). Incidentally, he was later sent out west to help put a stop to the ongoing Fujiwara no Sumitomo rebellion.

Fujiwara no Hidesato

Hidesato and Sadamori put together an army of 4,000 men and went to take on Masakado. Lucky for them, as it was farming season, Masakado had sent the majority of his men back to their hometowns, leaving himself with only 1,000 or so at hand. When word reached him of the impending attack, he sent two generals out with a number of men to scout the situation. They found Hidesato and Sadamori and launched a preemptive strike but soon retreated after realising they had no chance of winning without the support of Masakado’s main army. Hidesato and Sadamori advanced on Masakado and the battle commenced. But even with his full 1,000 men, Masakado was still too heavily outnumbered. He had no choice but to retreat and hide out in his base while he waited for reinforcements to arrive.

Unfortunately, Hidesato had had the same idea. With a victory under his belt and increasing momentum, he was able to recruit new soldiers easily and strengthen his army further(local samurai were often very fickle. Too weak to defend themselves against the main force controlling their region, they would often switch sides at the smallest hint that a new, superior power was about to arrive). Meanwhile, Masakado jumped from village to village looking for any men that were still willing to join him, but eventually he was forced to give up his search and take on his enemies with the 400 he had left. Hidesato and Sadamori arrived on the scene. The final battle was about to commence.

At first Masakado dominated the battle. The wind was on his side, allowing his arrows to fly faster and straighter, killing a number of Hidesato and Sadamori’s men. 2,900 fled, leaving only an elite 300 behind and turning the tables in favour of Masakado. However, the wind soon changed direction, giving his enemies the upper hand. One swift arrow struck Masakado’s forehead, causing him to fall off his horse. He was quickly decapitated, putting an end to the battle, his rebellion and his empire, which had lasted a little short of two months. Once his death had been confirmed, the court sent more men to kill his remaining brothers and children.

The aftermath

The immediate aftermath of the rebellion was surprisingly uneventful. Hidesato and Sadamori were rewarded and gained themselves some degree of fame and notoriety not only among the court but also in the east. However, in the long run, this would have serious repercussions for Japan: Hidesato’s descendants would go on to control the north of the country for close to a hundred years; Sadamori’s descendants would go on to take full control of the court and, by extension, the entire country!

Perhaps even more significant, though, is the fact that the court’s appointed warrior, Fujiwara no Tadafumi, didn’t arrive in time to take down Masakado before a couple of mercenaries could get the job done, hinting at the rise of the samurai. It wouldn’t be long before the court realised that their army was obsolete. If another rebellion occurred, they would have no choice but to ally themselves with samurai clans to take down their enemies, meaning they would have to reward those clans with land and status, allowing them to grow in power. In short, it spelled the end of the court’s rule over the country.

The Curse of Masakado

As for Masakado, along with Sugawara no Michizane and Emperor Sutoku, he came to be remembered as one of the three vengeful spirits of the Heian era. After being decapitated, his head was transported to the capital, where it was put on display for all to gaze upon. It apparently continued to live for several months without decaying and spent its days laughing at people and taunting them, demanding they tell him where his body was(I told you war chronicles couldn’t be trusted). And then one day, it emitted a blinding white light and flew off to Kantō, settling in an area of land which is now a part of Tōkyō.

The head was buried in the exact spot it landed and the grave remains today, mainly because no one is brave enough to move or demolish it. America’s GHQ tried to bulldoze the area after the Second World War to turn it into a storage facility, but as the bulldozer neared the grave, it apparently flipped over, killing the driver(this part wasn’t in the war chronicles. I have no explanation whatsoever for it). More recently, a famous Japanese comedian kicked the grave in an effort to prove the curse wasn’t real. He didn’t die nor was he harmed in any way, but his career did take a significant slump in the following few years.

And so Masakado’s grave remains, awaiting its next victim. Who will it be? If you ever find yourself in Tōkyō, why don’t you try giving it a kick yourself? Worst that will happen is you die, but whatever the outcome, you’ll be remembered for all time as a blurb at the foot of Masakado’s Wikipedia page.