Ten battles that changed the course of Japanese history

Japan has experienced many battles in many forms over its long and varied history, from small personal skirmishes fought between political rivals and samurai clans to full-scale conflicts between groups of 100,000+, and even wars that lasted as long as a decade. Most had little to no impact on the country’s history and remain in the history books purely to give us a deeper insight into the small factors that contribute to major change over the course of time. In some cases, they exist solely for the purpose of entertainment. But every so often, a battle occurs that changes the shape of the entire country. In this article, we’re going to be looking at ten such battles and studying the factors that led up to their outbreaks as well as the effects they had on the country.

The Jinshin War (672)

In the years leading up to his death, Emperor Tenji began to alienate himself from his younger brother, Prince Ōama. Most likely, he wanted to make it apparent that he had no intention of naming the prince his successor. When the emperor fell sick, his brother went to visit him. Before he could enter the room, however, one of the emperor’s closest aides advised him that the emperor was planning on assassinating him. Prince Ōama took this advice on board and explained to his brother that he should name his wife as his successor and have her hold the throne until his son was old enough to take her place. As an additional sign that he held no ambition to ascend the throne himself, he shaved his head that night and led his family to Yoshino in the south of Nara to start a new life as a monk.

The following year, after Emperor Tenji’s death, Prince Ōama led his family to the former capital, Asuka, and amassed an army to advance on the former emperor’s son, Prince Ōtomo. The battle lasted close to a month and ended with the new capital, Ōtsu, being taken, and Prince Ōtomo being forced to flee and kill himself.

When the dust had settled, Prince Ōama ascended to the throne as Emperor Tenmu. Rather than rely on his aides to help him run the court―as the majority of emperors up until that point had―he assigned a number of major court roles to his wife and sons and taught them to continue relying on each other even after his death.

He is credited as being the first emperor to refer to himself and his ancestors as ‘tennō'(天皇). He was the first emperor to refer to Japan by its current name of ‘Nippon'(日本). But the most significant of his achievements has to be the Kojiki and Nihonshoki―Japan’s oldest remaining history books, documenting the history of all emperors up until the end of the Asuka era and linking the Imperial Family to the gods. This one small act ensured that Emperor Tenmu’s line would continue to be revered through the ages to come, and it even helped to save the Imperial Family from extinction when the samurai rose to power. For this reason, Emperor Tenmu’s victory in the Jinshin War is one of the most significant events in Japanese history.

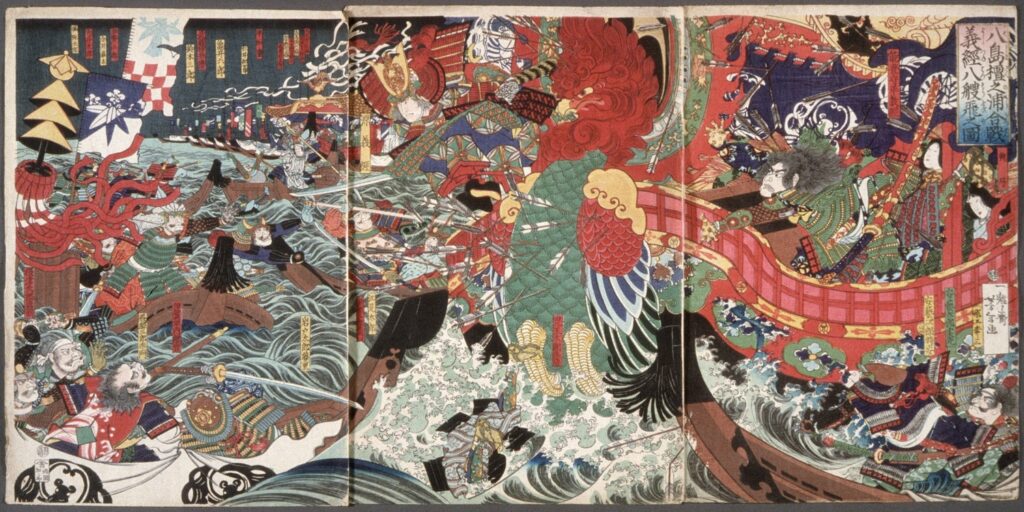

The Genpei War (1180 – 1185)

The Taira and the Minamoto had shared a complex relationship for centuries. In modern terms, I suppose you could call them frenemies. That all changed in 1159, however, when Minamoto no Yoshitomo rebelled against the court and had to be taken down by Taira no Kiyomori. A little short of a decade later, the Taira ruled the country and the few remaining Minamoto stragglers were struggling to survive. But all this was about to change; many were becoming dissatisfied with the Taira’s sudden power expansion. The time was ripe for another Minamoto rebellion.

Yoshitomo’s son, Yoritomo, took on the challenge, uniting the east against the wrath of the Taira. His cousin, Yoshinaka, put together his own crack team and made it a three-horse race. The battles continued for six years and ended with Yoritomo emerging victorious over the Taira(in no small part due to the help of his younger brother, Yoshitsune). Having got half the samurai in the country to join his cause and having destroyed the other half, the court was powerless to stop him. Retired emperor Go-Shirakawa had no choice but to award Yoritomo the title of shōgun and allow him to establish Japan’s first shōgunate in his base of operations, Kamakura.

However, being the first shōgunate meant not having a predecessor off whom to base a system of rule. For this reason, much of the Kamakura era was spent trying to find a way to maintain the shōgunate’s power over the court while keeping samurai across the country happy via a process of trial and error. It was a long and difficult road paved with betrayals and the occasional culling, but it paved the way for almost 700 years of samurai rule.

If you want to learn more about the Genpei War, check out my four-part series that covers all the major battles and events.

The Jōkyū War (1221)

A little after Yoritomo established his shōgunate, retired emperor Go-Toba made a bid to try to end it―or at the very least restore the balance of power in favour of the court. He led an army of 20,000 east to take on the might of the samurai. In response, Hōjō Yoshitoki, the shōgun’s right-hand man and the person effectively in charge of the shōgunate, sent his son and brother out west to meet this army with just a handful of soldiers. They went town to town gathering as many men as they could while slowly making their way towards the capital. It’s said that by the time they arrived, they had amassed an army of 190,000!

With a force that big, there was little chance of them losing the battle. Moreover, that army consisted of experienced soldiers, trained to fight from a young age, many of whom had fought in the Genpei war. The court’s army too contained some samurai who still weren’t sure where their loyalties lay, but it wasn’t enough to tip the scale. The shōgunate drove the court back to the capital and hunted their remaining soldiers down until they had no choice but to surrender.

There isn’t a person alive today with any knowledge of the history of the samurai who would have bet on the court winning this battle. Samurai vs court nobles? Of course the samurai are going to win. Hands down. It’ll be a bloodbath! However, this wasn’t the case at the time; this was the first time in history the samurai had taken on the court without the assistance of any of the noble families.

The shōgunate was still a fledgling organisation. Many weren’t sure if it was going to be able to stand the test of time. In modern terms, it would be akin to quitting a job at Google to work for a promising startup company. This is why many samurai elected to stay with the emperor. However, it’s important not to forget that Google too began its existence as a startup, and every now and then a startup takes off and becomes a mega-conglomerate that takes over the world. This turned out to be the case for the shōgunate.

Yoshitoki exiled the retired emperor and his sons, established a barrack in the capital to keep an eye on the court’s activities and confiscated the land of all who had taken the side of the emperor. Although the court remained the country’s official power, there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that the shōgunate now ran the show.

The Genkō War (1331 – 1333)

It would take over a hundred years before an emperor had the guts to take on the samurai once more. Emperor Go-Daigo made the decision to attempt the impossible not so much because he wanted to restore power to the court, but more so because he wanted to remain emperor. In the middle of the Kamakura era, an ascension dispute called for shōgunate intervention, creating a precedent that gave the shōgunate authority over all ascensions from that point forth. When Go-Daigo took the throne, it was agreed that he would hold the position of emperor until his nephew came of age, at which point he would step down. Needless to say, when the time came, he was slightly more reluctant to do so than he had initially expected.

His first attempt at a coup d’etat in 1324 was a non-starter; the plan leaked, all involved were exiled, the emperor got a slap on the wrist and the shōgunate put the whole affair to rest. Seven years later, he tried again. Once more, the plan leaked. This time he escaped to a castle fortress in Mount Kasagi south of the capital and sent out scouts to find any samurai who would be willing to join his cause. Luckily for the emperor, things had changed dramatically since the Jōkyū war: having been impoverished by two Mongol invasions, the shōgunate was weak and no longer had as tight a grip on the samurai scattered around the country as it used to. Many were more than willing to sign up with the emperor.

As the fighting continued, more and more samurai began to switch sides. Among them were two men who would play a key role in the battles to come: Ashikaga Takauji and Nitta Yoshisada. After a year of fighting, Takauji succeeded in occupying the capital, and Yoshisada took down Kamakura, restoring power to the court for the first time in almost 150 years.

This should have been the end of it. However, Go-Daigo got cocky. He dished out the highest positions within the court to his friends who had sat on their backsides and done nothing for the duration of the war rather than granting the samurai who had earned him his position the rewards they deserved. On top of that, he ignored the advice of those samurai and made it clear he intended to phase them out of his rule. Takauji became disgruntled. Having reached his limit, he amassed a small army and occupied what was left of Kamakura, encouraging samurai everywhere to join his cause. Yoshisada, on the other hand, remained loyal to the emperor. This sparked another year-long war between the two forces, which resulted in Go-Daigo fleeing to Yoshino(a standard for any emperor who fears for his life), and Takauji establishing the Muromachi shōgunate.

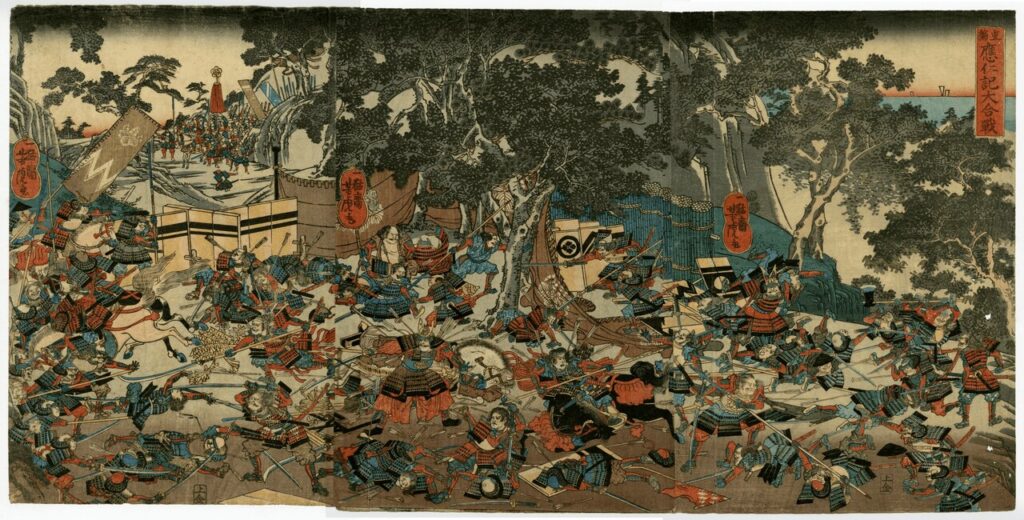

The Ōnin war (1467 – 1477)

The Muromachi era was a volatile time. The assassination of a shōgun coupled with an ongoing war in the east was taking its toll on the country, and the current shōgun was more concerned with his personal problem―the fact he didn’t have an heir―than trying to sort the mess out. As more and more families in the east took advantage of the war to try to usurp power from their clans’ leaders, families in the west, seeing that the shōgunate was powerless to stop this chaos, began to copy the trend.

Among these families were the Hatakeyama and the Shiba―two of the three families from whom the position of kanrei was chosen. Hosokawa Katsumoto, a member of the third family and the current kanrei, picked a side in both feuds. His father-in-law, Yamana Sōzen, with whom he had been having some personal issues, picked the opposing sides. As two small armies began to form in the capital, the shōgun’s wife gave birth to a son. Since the shōgun had already promised the position of his successor to his younger brother, a feud began to form within the shōgunate itself. Both the shōgun and his brother joined Katsumoto and Sōzen’s armies.

Before long, war broke out. It was a long and complex war that lasted 11 years, during which time the leaders of the two armies died of illness, and the key players switched sides multiple times. In the end, it faded out before a clear winner could be decided. But while the result of the war may have been anti-climactic, its consequences were anything but; most of the capital lay in ruins, and the shōgunate managed to prove definitively that it was powerless to put a stop to any kind of quarrel, feud or rebellion.

This sparked a 150-year long battle royale with samurai leaders everywhere invading and attacking their neighbouring territories to try to gain as much land as possible in a bid to become the next ruling faction. And while the Muromachi shōgunate itself survived for another 100 years, the shōgun was nothing more than a puppet to be controlled by whomever was strong and smart enough to work their way up to the top of the samurai hierarchy.

The Honnōji incident (1582)

In 1582, one man was on the verge of winning the aforementioned battle royale: Oda Nobunaga. In the space of 30 years, he went from controlling a small part of a minor region of Japan to having a mini empire consisting of over 15 provinces, alliances with a number of the country’s top daimyō and two of his best men working to expand his territory to the north and west. He was set to take over the entire country within a matter of years, and he would have pulled it off had it not been for the betrayal of his third best man.

Nobunaga was staying the night in a small temple in the outskirts of the capital known as Honnōji, resting up before his planned trip out west. He had less than 150 men to protect him, but that was okay because the capital was under the jurisdiction of Akechi Mitsuhide, his third best man. That night, Mitsuhide led an army of 13,000 to Honnōji, surrounded and set fire to the temple, killing Nobunaga’s men and forcing Nobunaga himself to retreat to the very back of the temple complex to kill himself.

The reason Akechi Mitsuhide decided to turn on his master and end Nobunaga’s empire is one of the greatest mysteries of Japanese history. Many theories exist, but none are without their holes, and no documents from the time are able to prove even the most likely of them. Whatever the reason, Nobunaga’s ambitions ended that day, awarding his best man, Hashiba Hideyoshi, an opportunity he had never dreamed possible. Hideyoshi hastily returned from his crusade out west, convinced a number of local samurai to join up with his small army and killed Mitsuhide in battle. Having avenged his master, there were few men in the country who could stop his subsequent rise to power.

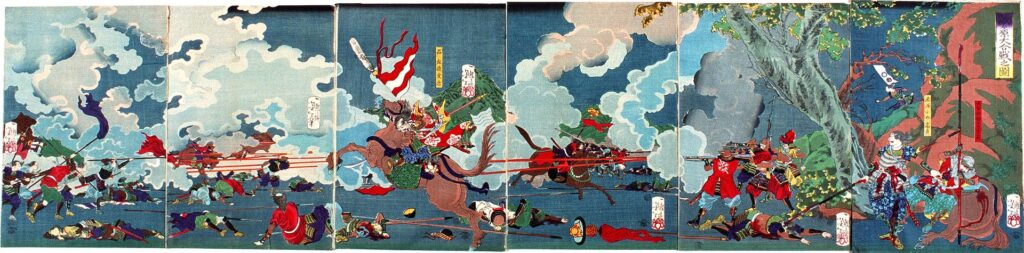

The Battle of Sekigahara (1600)

After uniting the country and putting an end to the constant fighting that had been continuing for over 100 years, Toyotomi Hideyoshi(as Hashiba Hideyoshi was now known) died at the age of 61. As his son was not yet old enough to take over his new system of government, two teams of five men each were established to rule in his stead. One consisted of five of the most powerful daimyō in the country; the other of Hideyoshi’s five top bureaucrats.

Tokugawa Ieyasu, the most powerful of the five daimyō, had risen through the ranks of samurai society early on by allying himself with Oda Nobunaga. By later cooperating with Hideyoshi after Nobunaga’s death, he amassed an even greater amount of land, allowing him to become the most powerful man in the east. Now, with his greatest obstacle out of the way, it was finally his turn.

Through a series of manipulative tactics, Ieyasu spent the following two years subduing the power of the other four daimyō and forming alliances with smaller families by marrying off his sons and adopted daughters. Many were wary of his actions, but only one man took action to stop him: Ishida Mitsunari―Hideyoshi’s top and most loyal bureaucrat. Mitsunari sent his scouts around the west seeking out samurai to join his cause. Having been ostracised by Ieyasu, the majority of the remaining leading daimyō were happy to join up with him. After amassing an army large enough to rival Ieyasu’s, Mitsunari marched his men to the capital and attacked Fushimi castle, where a number of Ieyasu’s men were stationed. Ieyasu, who was in the east at the time, set out west. After taking down Fushimi, Mitsunari headed east. The two met in a large plane surrounded by mountains known as Sekigahara.

What ensued was the most famous battle of Japanese history, involving almost 200,000 soldiers and most of the biggest names of the time. Despite its grand scale, however, the battle was over in just six hours. Mitsunari’s men succeeded in driving back Ieyasu’s army for the majority of the battle, but a number of betrayals in the final two hours turned the tables. Defeated, Mitsunari’s remaining men fled to the mountains.

Mitsunari was found and executed a month after the battle. Ieyasu confiscated the land of those who had taken his side and used it to reward his allies. With every samurai in the country now either allied with him or subdued, he had complete control of the country. Three years later, the emperor awarded him the title of shōgun, marking the official start of the Edo shōgunate―a 260-year long era of relative peace.

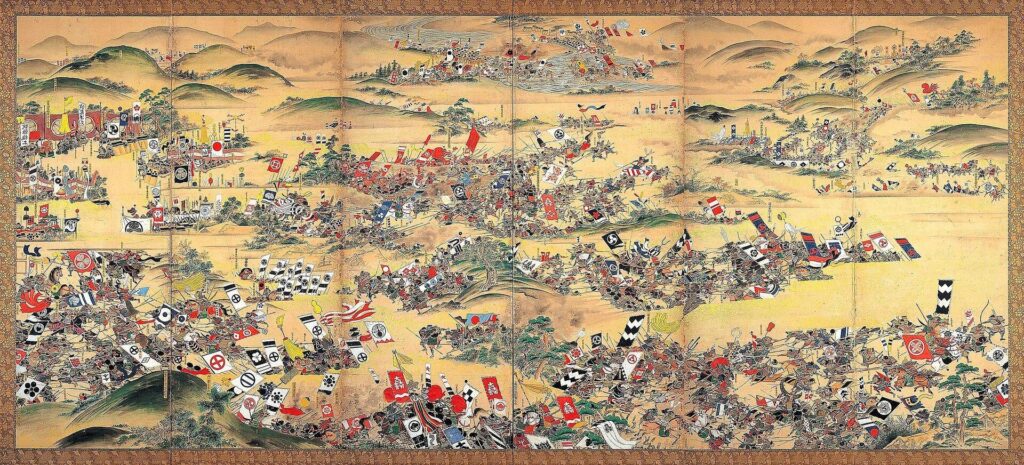

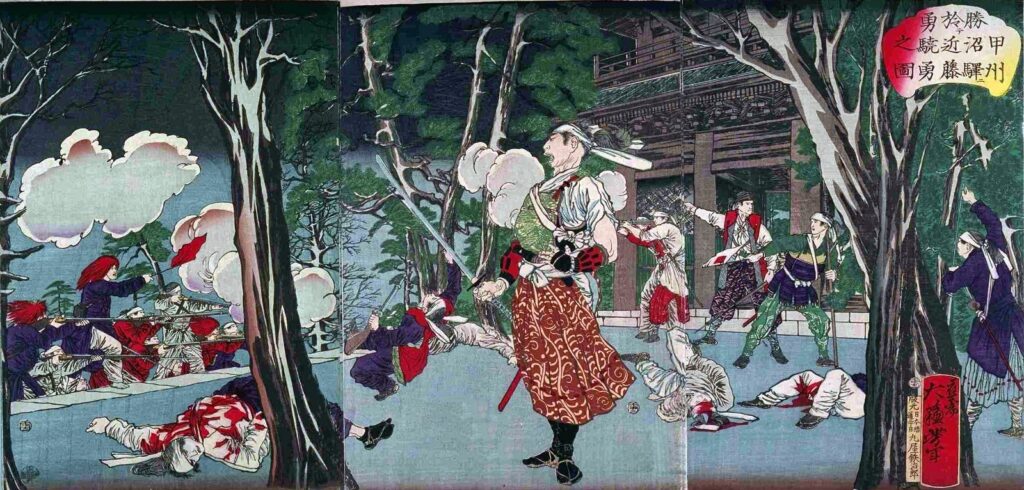

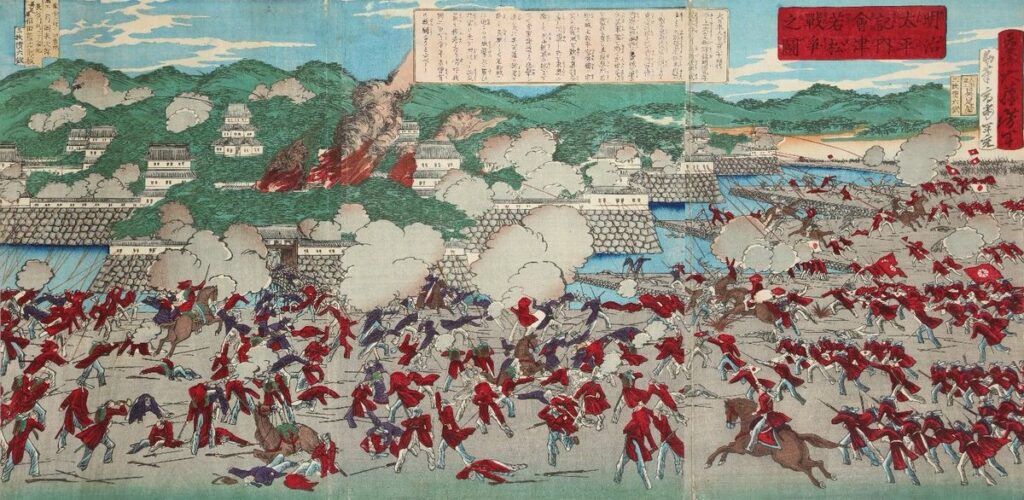

The Boshin war (1868 – 1869)

The Edo shōgunate was the most successful of Japan’s three shōgunates. Aside from a couple of battles that broke out in the early phase of the Edo era, the country finally got to experience a long-deserved period of peace. That would all end in 1853, however, when a US naval officer by the name of Matthew Perry sailed his ships into Uruga port and demanded Japan form a trade agreement with the USA.

Having locked out foreigners for the past 250 years, the shōgunate was divided on the issue of opening the country’s gates. Influential daimyō from around the country were brought to Edo to offer their opinions. Most were against the suggestion. The shōgunate, on the other hand, knew it wasn’t powerful enough to risk war with America.

This kicked off ten years of internal conflict, during which a number of wealthy domains formed and broke alliances with one another and changed their stance on foreign policy numerous times over. It all came to a head in 1866 when Satsuma han and Chōshū han teamed up to take on the shōgunate, aided by Tosa han. The three domains succeeded in backing the shōgun into a corner and forcing him to relinquish control of the country to the emperor.

While the shōgun reluctantly agreed to the dissolution of the shōgunate, he assumed that with his expertise and knowledge of the political situation of the country, he would be granted a place in the emperor’s newly-formed government. Once it became apparent that wasn’t going to happen, however, he started a war between the remaining shōgunate army and the Satsuma-Chōshū-Tosa coalition.

This war continued for over a year and spread across the entire north and east of Japan. One by one the new government took down the hans that remained loyal to the shōgunate until only a handful of soldiers remained in Ezo―the massive island to the north of Japan currently known as Hokkaidō. One final lengthy battle ended the shōgunate for good.

When the war was over, the Meiji government relied on consultants from the USA, Britain, France and Germany to establish its new system of rule. In search of inspiration, a small group consisting of a number of the government’s top members travelled the world to study the political systems, architectural styles, infrastructure and engineering methods of various countries. Over the next twenty years, Japan would go through a series of changes that slowly Westernised the small island country and made it a part of the modern world.

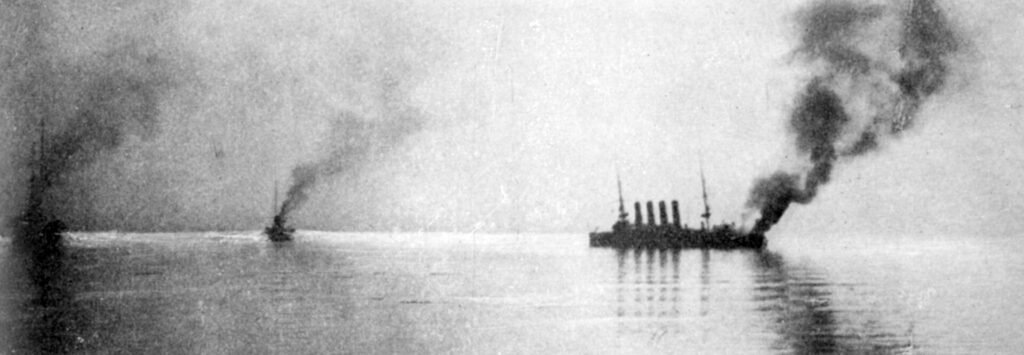

The Russo-Japanese War (1904 – 1905)

A little into the Meiji era, Japan defeated Qing, allowing it to add Taiwan to its portfolio of land. Those of you who are familiar with this war may be wondering why it didn’t make the list. While it marked Japan’s first major victory over a foreign enemy and was indirectly responsible for the subsequent colonisation of certain regions of Qing by a number of European nations, the victory itself just wasn’t as impressive as it sounds on paper; Qing had already been weakened by Britain and France earlier in the century, and having not yet embraced Western ideologies, the country didn’t have access to the advanced weaponry that Japan had been able to obtain. Qing’s loss was inevitable.

Russia was a different story. With two of the largest fleets of ships in the world at its disposal and an army of close to 1.5 million, Japan’s chances of survival―let alone winning―were slim. Perhaps it was Russia’s complacency that led to Japan taking out its Pacific fleet and forcing it to have to send the larger, more powerful Baltic fleet to swat them away. The Baltic fleet didn’t fare much better, however; of the 38 ships sent to drive Japan away from Russian-controlled sea, 21 were destroyed and 6 were captured before Russia finally surrendered.

The world was blown away; this was the first time in history that a non-white race had defeated a white race in a war of that scale. It gave hope to colonised nations everywhere that they could one day earn their freedom through battle. Ukrainian refugees who had fled to Saskatchewan founded a village named ‘Mikado’―a Japanese term used to refer to the emperor. An Egyptian journalist wrote a book entitled ‘The Rising Sun’, praising Japan for embracing the modern world without losing its identity and explaining how Egypt’s rulers should follow the example set by the Meiji government and oppose Britain’s occupation of their country.

In India, the people began an independence movement to expel Britain from their land. (It’s somewhat ironic that Japan’s victory encouraged so many colonised nations to stand up to Britain, considering the fact that the alliance formed between Japan and Britain in 1902 is largely responsible for the courage Japan needed to declare war on Russia in the first place.)

Before I end up with modern history buffs breathing down my neck, though, I will concede that like Japan’s victory against Qing, its victory against Russia was not as impressive as it may have appeared. The headlines read ‘Japan defeated Russia’, and that was all that was needed for the major powers to change their view of the rising Asian nation and, later, invite it to be a founding member of the League of Nations. However, had Russia had the will to keep the war going, it could have sent as many waves of the Baltic fleet east as necessary to deplete Japan’s resources and force a surrender.

As luck would have it for Japan, though, Bloody Sunday broke out towards the end of the war, and Russia was too busy worrying about the impending revolution to focus on battle. So the Russian government abandoned their interest in Manchuria, acknowledged Japan’s right to ‘protect’ Korea and surrendered a small amount of land on the condition that they would not pay a single ruble in compensation. And so while the victory would pay off in the long run, in the short run, the lack of compensation left Japan’s balance sheet in the red and caused riots among the people.

The Pacific War (1941 – 1945)

This war needs no explanation. The factors that led to Japan entering it are as numerous as they are complicated and deserve an article of their own. Regardless of these factors and regardless of the details of the war, there is no denying that the outcome brought about perhaps the biggest change to Japan in all its history. Unlike most of the other battles detailed in this article―where the outcome was a change in leadership, a change to a different system of feudal rule or the spread of imperialism―the outcome of this war brought about a period of peace which has been continuing for the past 80 years.

How long this peace will continue is anyone’s guess. But if history has taught us anything, no period of peace lasts forever. We can only hope that the decisions being made by the country’s leaders today are the decisions necessary to keep this period going for as long as possible.