The Genpei War Pt. 1

Welcome to the first of this four-part series on the Genpei War. This is going to be a long one, and rightfully so. The Genpei War was the culmination of two situations that had been developing for centuries: the rise of the samurai and the deterioration of the court. Over the course of these four articles, we’re going to be covering all the major players, events, battles and twists that make up this epic five-year period of Japanese history. Before we dive into the war itself. though, we have quite a bit of background knowledge to cover. Let’s start by figuring out what claused the court’s decline.

The Decline of the Court

By the middle of the 12th century, the court had become too top-heavy. The cloistered system of government first established by Emperor Shirakawa in 1086 as a way of taking back power from the Fujiwara family had resulted in instances of as many as four retired emperors all coexisting within the palace walls and fighting over who gets to control the current emperor. While this system succeeded in returning power to the Imperial Family, the decades-long power struggle shifted the court’s focus away from the capital’s defences and caused its army to become lax.

This situation forced emperors and nobles alike to have to rely heavily on samurai clans, whose assistance they rewarded with vast amounts of land and high-ranking court titles. Slowly but surely, the samurai used this land and these titles as a power base to make their way to the capital and snake their way up the chain of command. Finally, in 1185, one samurai succeeded in usurping the last of the court’s power. As some of you may not know who this man is, I won’t spoil the story for you. All will be revealed after we take a short break and look at the meaning behind the name ‘Genpei War’.

The Naming of the War

The name ‘Genpei’ is made up of two Chinese characters: 源 and 平. The secondary readings for these characters are ‘gen’ and ‘hei’ respectively. When put together, the ‘hei’ sound is changed to ‘pei’ to make it more pronounceable. This is how we arrive at ‘Genpei’.

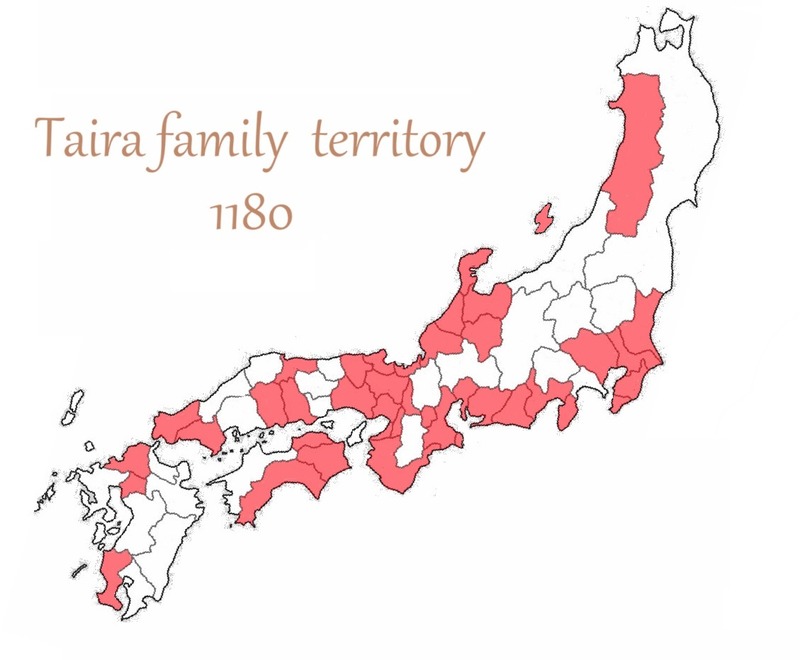

The characters’ primary readings are where we find the meaning of the name. Read ‘Minamoto’ and ‘Taira respectively’, they represent the names of the two largest samurai clans in Japan in the latter half of the Heian era. Both clans were distant relatives of the Imperial Family. In the early Heian era, when an emperor had too many children for the court to support financially, he would relegate a number of them by awarding them either the ‘Minamoto’ or ‘Taira’ kabane and giving them jurisdiction over areas far from the capital. The descendants of these former princes grew more powerful over time until their military power far surpassed that of the court.

And so the name ‘Genpei War’ refers to the fact that the majority of the major players in the war originated from either the Minamoto or Taira clans. This gives rise to the common misconception that the war was fought between two distinct sides: those with Minamoto blood and those with Taira blood. In actual fact, there were three sides, all of which contained members of both clans. Like most wars fought throughout Japanese history(or any country’s history for that matter), individual members of each family picked the side that offered them the best hope for personal prosperity.

The Genpei War’s Real Name

Before we finish up this discussion of the name and start looking at the war itself, I should explain that while the term ‘Genpei War’ is the name by which the war is most familiar, it’s actually just a nickname. The official name of the war is the ‘Jishō-Juei War’—the name being derived from the two Japanese periods over which the battles were fought. Now that we know how the war got its name, let’s find out how historians have studied it over the centuries.

Historical texts

Having taken place over 800 years ago, much of the information we have regarding the Genpei War is difficult to authenticate, and new theories are being formulated constantly. Obviously, the greater the number of historical sources that quote a certain fact, the more likely that fact is to be true. With this in mind, the text containing the greatest number of corroborative facts is the ‘Azuma Kagami’—an account of events that occurred throughout most of the Kamakura era, written from the perspective of the Kamakura shōgunate.

The next most verifiable text is the ‘Tale of the Heike’—an epic account of the history of the Taira. Although many of the details recounted in the story can be found in the Azuma-Kagami, since it is riddled with exaggerations, dramatisation and entirely made-up events, this text is regarded more as a work of fiction than a historical document.

Aside from these two texts, there are also a number of diaries written by noblemen who lived through the time of the war that can be used to verify bits and pieces. Naturally, the information contained within them has to be considered biased in favour of the court, and while they provide us with detailed reports of events that occurred within the capital, they can’t provide a first-hand account of any of the battles that took place.

Combined, these sources contain details of over 40 battles. However, many of these were small skirmishes that had little impact on the war. This series will only be covering the battles/events concerning the war’s main protagonists as well as those that had a significant influence on the flow of the war.

The Contenders

Next, let’s take a look at who was involved in the war. The Genpei War was, by and large, a three-horse race between Taira no Kiyomori, Minamoto no Yoritomo and Kiso Yoshinaka. Let’s take some time to familiarise ourselves with the backgrounds of these three leaders.

Taira no Kiyomori

In 1156, an incident known as the ‘Hōgen Rebellion’ broke out. This was a culmination of years of internal conflict among the Imperial Family, the Fujiwara and the Minamoto. All three families were divided. The various parties that formed from these divisions made alliances with one another, developing into two large armies, each containing members of all three families.

The rebellion pitted father against son and brother against brother, with every participant fully aware that the winning side would receive levels of success never before dreamed possible while the losing side would most likely face execution. The Taira, for the most part, managed to stay united. With the exception of a few rogue members, the majority of the clan fought together on the same side—the winning side.

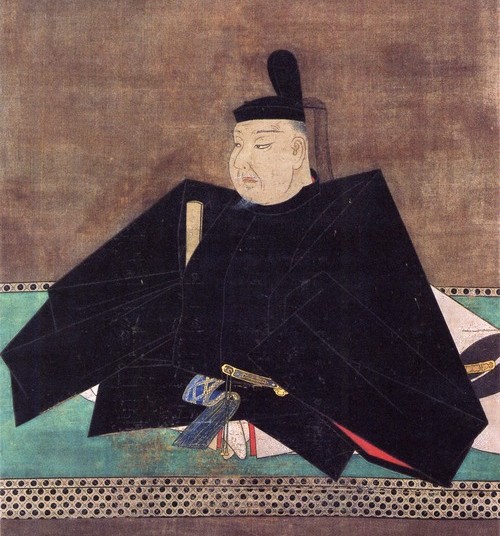

Taira no Kiyomori, the clan’s leader, was rewarded even more greatly than he had expected. Three years later, when a subsequent rebellion—the Heiji Rebellion—broke out, he was handpicked by the emperor to deal with the situation. When he succeeded in doing so, he and his family were rewarded with land and titles the extent of which no samurai family had been able to enjoy until that time.

There was no stopping the Taira now. With his foot firmly in the door of the court, Kiyomori used his newfound status to form connections with high-ranking officials, who, in turn, allowed him to rise through the ranks of the court and earn a title no member of a samurai family had ever held before: dajōdaijin—a title so prestigious, it only existed when someone deemed worthy of it appeared. In modern terms, it would be equivalent to a super-prime minister—someone so politically competent as to outrank even the existing prime minister. In short, Kiyomori had supreme and undisputed control over the court. To solidify his position and ensure the continuing prosperity of his family, he married his daughter to the emperor and had them bear a son, who was named the new emperor in 1180—the year the Genpei War broke out.

Minamoto no Yoritomo

Let’s return to the Hōgen Rebellion for a moment. Remember when I said that Taira no Kiyomori was on the winning side? Well, fighting right alongside him was none other than the leader of the Minamoto clan, Minamoto no Yoshitomo. While Kiyomori’s brothers and uncles had stood with their leader though, Yoshitomo stood on the opposite side to virtually every member of his family. That’s how sure he was that he’d picked the winning side. And while he had been right, victory came at the cost of his father and brothers. Even worse, the newly-crowned Emperor Go-Shirakawa—the ultimate victor—had Yoshitomo carry out their executions in order to prove his loyalty.

For all his trials though, Yoshitomo wasn’t rewarded anywhere near as handsomely as Kiyomori. This brings us back nicely to the Heiji Rebellion. This rebellion was initiated by a disgruntled Yoshitomo, who joined forces with a similarly frustrated member of the Fujiwara family to try to overturn the results of the Hōgen Rebellion. It didn’t go well; Kiyomori was called back to the capital to quell the uprising and Yoshitomo was killed along with a number of his sons.

Now, at long last, we come to Yoritomo, Yoshitomo’s third son. Ideally, Kiyomori would have had the 13-year-old killed along with the rest of his brothers. However, Kiyomori’s stepmother begged Kiyomori to spare the boy’s life on the grounds that he was the spitting image of her son who she lost ten years before. The validity of this story is questionable, but whatever his reason may have been, the fact remains that Kiyomori decided not to kill Yoritomo. Instead, he exiled him to the Izu peninsula. There, Yoritomo spent his adolescence under the guard of Hōjō Tokimasa, whose daughter he would eventually marry, biding his time until an opportunity arose to restore the Minamoto name.

Kiso Yoshinaka

I mentioned before that Minamoto no Yoshitomo turned on his family. This wasn’t a spontaneous decision, however, nor was it as difficult a decision as I may have made it out to be; the Minamoto family feud actually predates the Hōgen Rebellion. The main reason for Yoshitomo’s betrayal was a difference of opinion between himself and his father, Tameyoshi, regarding who the clan should curry favour with within the court. Tameyoshi believed the Fujiwara were their best bet; Yoshitomo opted for noblemen working directly under Cloistered-Emperor Toba. After months of dispute, Yoshitomo parted ways with his father and moved east to start a new branch of the Minamoto. Tameyoshi sent another of his sons, Yoshikata, to keep him in check.

In 1155, less than a year before the Hōgen Rebellion, Yoshitomo sent his eldest son, Yoshihira, to attack Yoshikata. Yoshihira killed his uncle, allowing his father to take over a significant amount of land in the east. Yoshihira also intended to hunt down and kill Yoshikata’s two young sons, but they were rescued and hidden by Yoshikata’s retainers before he could carry out this plan. The elder son was sent to the capital, where he was taken into the custody of Minamoto no Yorimasa—a member of a distant Minamoto clan, with ties to the Taira. The younger son was sent to a small village known as Kiso in the south of Shinano province. When he came of age, he was granted the name Kiso Yoshinaka.

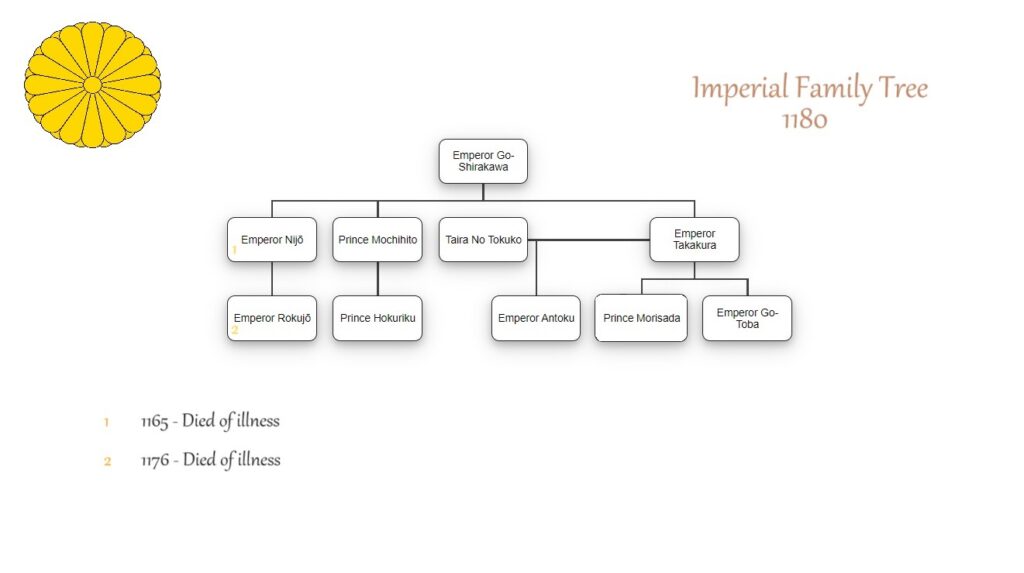

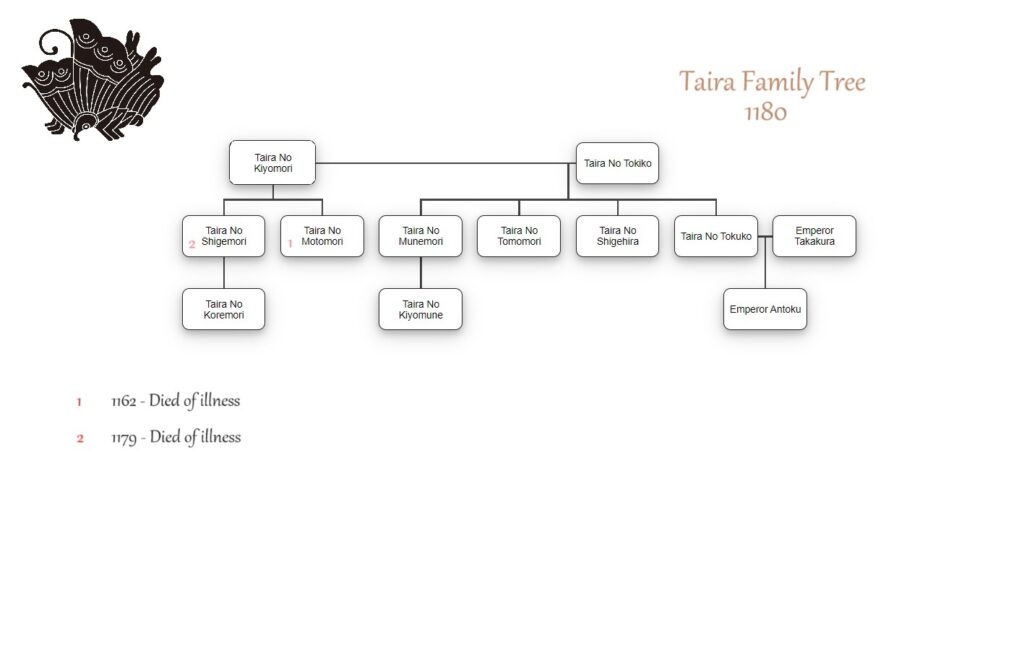

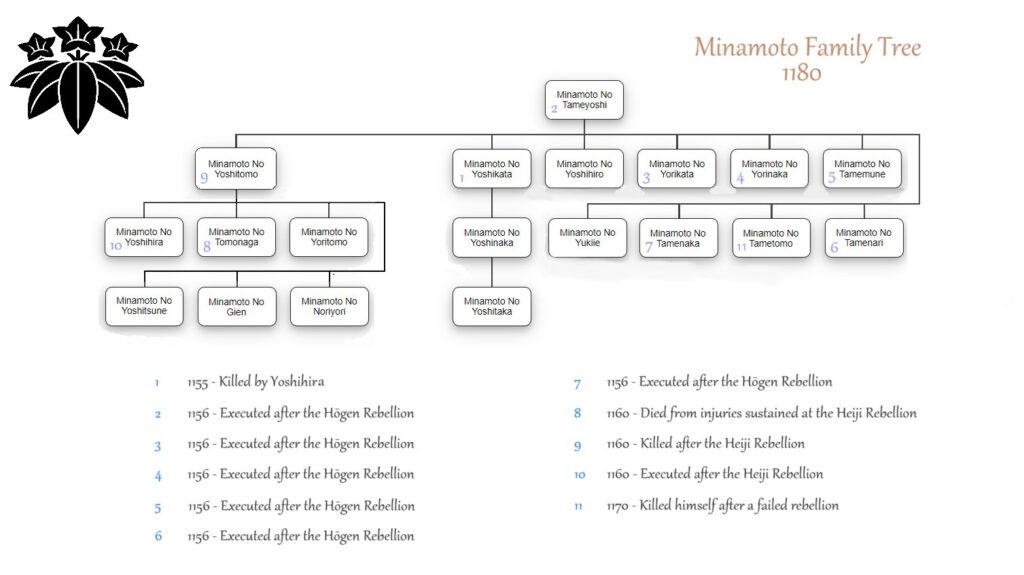

Family Trees

For more details on everyone who was involved in the Hōgen and Heiji Rebellion, check out the family trees below. There are going to be a number of new names thrown out constantly throughout this Genpei War series, so I recommend checking back regularly until you get the gist of who the main characters are and how they relate to one another. Please be aware, however, that these family trees are incomplete; they only contain the members of each family relevant to the war and its backstory. As samurai leaders often had upwards of 20 children, it would be impractical to include every one of them. With that final disclaimer out the way, let’s finally take a look at the Genpei War itself.

The Genpei war

Prince Mochihito

So which of our three protagonists was it that blew the horn and kicked off five years of fighting? Actually, it was none of them. The war was started by Cloistered-Emperor Go-Shirakawa’s third son, Prince Mochihito. Up until the moment it was announced that Kiyomori’s grandson would be the next emperor, Mochihito had believed he was next in line. To be fair, this ambition was more than just a pipe dream; his older and younger brothers had already been selected in the past, he was known for his keen intellect, and to solidify his chances, he even had himself adopted by his aunt to avoid being sent to the priesthood and gain access to her vast real estate portfolio, which he planned to use as an economic base to fund his campaign. In all likelihood, had Kiyomori not risen to power, Prince Mochihito would have been the next emperor.

If Mochihito was already salty about losing out on his chance of becoming emperor, he was really salty when Kiyomori confiscated a large portion of his land. This was the clincher; this meant war. But how to go about it? Mochihito needed allies—people with power and connections.

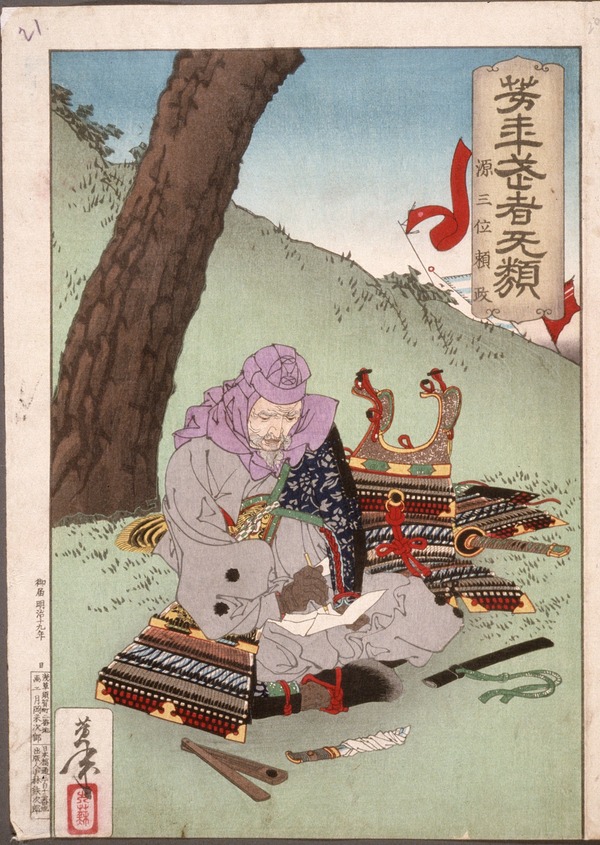

Minamoto no Yorimasa

The first man he approached was Minamoto no Yorimasa, who, as I hinted at earlier, had managed to reach a high-ranking position within the court due to the ties he’d formed with Kiyomori during the Hōgen Rebellion. Now, for whatever reason, Yorimasa decided to turn his back on the Taira and join forces with Mochihito. I say ‘for whatever reason’ because no historical document records a clear motive. There are mentions of a quarrel between Yorimasa’s and Kiyomori’s sons over a horse, and there are several theories regarding the stagnation of his career during the years leading up to the war, but no one knows for sure why Yorimasa decided to gamble on the young prince.

Whatever the reason, Yorimasa and Mochihito sent Minamoto no Yukiie around the country to seek out any remaining members of the Minamoto clan who might be willing to join the cause. Yukiie headed south, where he quickly got himself discovered. Word reached back around to the Taira, and Mochihito was forced to flee to Onjōji.

Onjōji

Along with Enryakuji and Kōfukuji, Onjōji was one of the three most powerful temples of the time. The priests harboured the royal fugitive until the Taira came knocking on their door. Mochihito sent out messengers to the other two major temples asking for assistance, buying Onjōji some time. The last thing the Taira wanted was to have the wrath of the three largest religious armies in the country bearing down on them. The two sides reached a stalemate, neither willing to make the first move until they knew where Enryakuji and Kōfukuji stood.

A few days later, the Taira got tired of waiting and decided to launch their attack. Luckily for Mochihito, Yorimasa’s cover hadn’t yet been blown. In fact, ironically, the Taira even put him in charge of the attack on Onjōji! The night of his commission, he burned down his estate, led 50 soldiers to Onjōji and joined up with the prince.

Elsewhere, Enryakuji decided to ally itself with the prince. The Taira advanced on the main temple complex, forcing back enough of the sect’s army to make sure they were no longer a threat. Onjōji, sensing their position was fragile, handed the prince 1,000 or so men and sent him and Yorimasa down south to Kōfukuji, who they deemed better equipped to help the cause. The Taira responded by sending an army led by Shigehira and Koremori to block the prince’s path.

The Battle of Uji

After a long day of travelling, Prince Mochihito became so sleepy that he fell off his horse. As night would soon fall, the small army decided to take refuge in the nearby town of Uji. The river that flowed through the area was famously wild and would provide good defence. Yorimasa and his men set about removing the planks from the bridge to ensure the Taira army had no way to cross.

When the Taira arrived, arrows began to fly. With no way to cross the river, the two armies had no choice but to engage in a range battle. This continued for a while until the Taira hatched a plan to create a makeshift dam along the length of the river by tying their horses together. The bowmen held the prince’s army at bay while 300 men connected their steeds, slowly advancing them along the rapidly flowing water, careful not to have them swept away by the fierce current. When the dam was complete, the entire army was able to cross to the other side of the river with ease.

Heavily outnumbered and their last line of defence having been broken, Yorimasa sent 30 men to protect Mochihito and aid his escape before retreating to Uji’s infamous Byōdōin Temple and killing himself before the enemy could get to him. Mochihito fled south, aiming for Kōfukuji, but the Taira army hunted him down. One skillfully-timed arrow pierced his armour, causing him to fall off his horse. The rebellion was over.

After confirming the prince’s death, the Taira seized his children and handed them over to various temples to be raised as priests. One, however, escaped and fled east, where he was adopted by Kiso Yoshinaka. Interestingly, Yoshinaka’s older brother, who had been raised by Yorimasa, died in the battle alongside his adoptive father. It was almost as if fate had sent Mochihoto’s son as a replacement for Yoshinaka’s lost family member. However, with his father having been killed by Yoritomo’s brother, and his brother having been killed by Kiyomori’s son, Yoshinaka was out for both Minamoto and Taira blood.

| Taira | Minamoto | Kiso |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

With the Genpei War officially underway and the first victory having gone to the Taira, I think this is a good place to take a break. Join me in part two to see how this epic three-horse race plays out.