The Isshi Incident

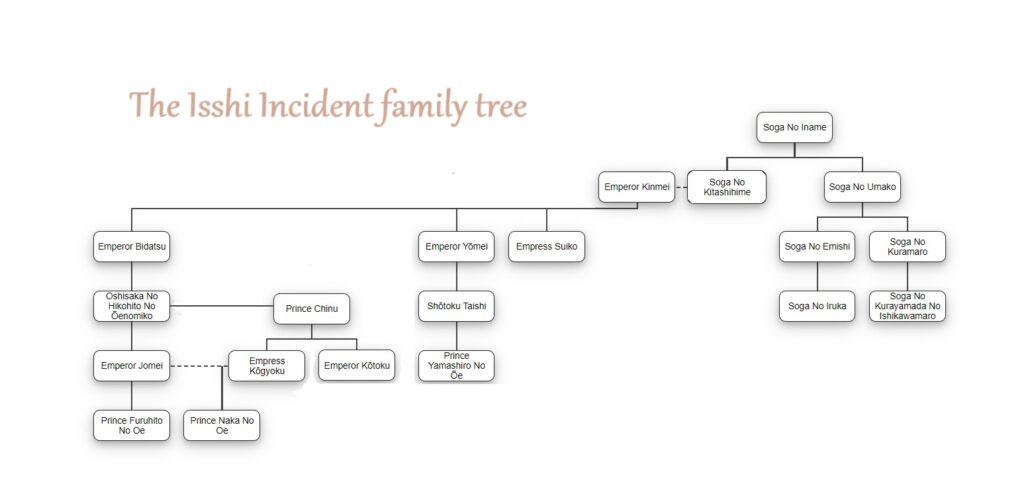

645 was a big year for Japan. Not only did the Imperial Family regain control of the court, but it also conducted the nation’s first set of political reforms: the Taika reforms. Unfortunately, as is more often than not the case with history this old, the texts detailing the events are difficult to trust. The two texts that document the tale were both written around 100 years after the event and, more importantly, were produced by the families of the two victors: Prince Naka no Ōe and Nakatomi no Kamatari. It goes without saying that both documents are horribly one-sided. Before we even dive into the ‘facts’, let’s take a look at the names of the members of the Soga family―the victims of the incident.

- Soga no Umako(蘇我馬子)

- Soga no Emishi(蘇我蝦夷)

- Soga no Iruka(蘇我入鹿)

These are unusual names to say the least, even for the Asuka era. The ‘馬’ character in Umako means ‘horse’. The ‘鹿’ character in Iruka means ‘deer’, and the name Iruka itself can mean ‘dolphin’. Emishi is the most blatant of all; the name and characters are the exact same as those used for the indigenous people of Japan who lived in the north of the country―a people the court was trying to subdue.

It can’t be a coincidence that three related people who controlled the court for more than 50 years before being defeated by the Imperial Family have such strange and(possibly for the times) insulting names. This begs the question: if the names have been fabricated, what other details surrounding the event have been tinkered with? Since we currently have no way to answer that question, let’s take a look at the Isshi Incident as history records it.

The Isshi incident

In the early 7th century, the court was ruled by three people: Empress Suiko; her uncle, Soga no Umako; and her nephew, Umayado no Miko(whom I’ll be referring to in this article by his more popular name of ‘Shōtoku Taishi‘). Umako and Shōtoku Taishi had worked together to take down their political opponents before placing Suiko on the throne as Japan’s first female ruler. The three ushered in an era of peace to the country that lasted until the mid-620s, when they all died within four years of one another.

After Umako’s death, his son, Emishi, took over his position. Two years later, when the empress died, Emishi backed Prince Tamura, a grandson of a former emperor, for her successor. The other candidate, Prince Yamashiro, was Shōtoku Taishi’s son. Although Emishi was related to Prince Yamashiro, he felt that backing him would make too powerful a statement; it may have caused certain members of the court to believe that he wished to usurp the court’s power and control the emperor as his father had controlled Empress Suiko. So instead, he chose Prince Tamura, who was married to his daughter, thereby still providing him familial ties to the court and allowing him to usurp its power in a slightly more discreet manner.

The rise of the Soga

Prince Tamura ascended the throne as Emperor Jomei and ruled until his death in 641, after which his wife ascended as Empress Kōgyoku. Emishi passed his duties to his son, Iruka, and the two proceeded to flaunt their power by way of building tombs comparable in size and shape to those of members of the Imperial Family, publicly performing ritualistic dances normally reserved for members of the Imperial Family, renaming their estate ‘Mikado’―a name reserved for the emperor’s abodes―and referring to Iruka’s sons as princes. (All of these actions are open to interpretation, and recently historians have begun to formulate a number of theories that suggest they weren’t intended to step on anyone’s toes.)

Iruka selected Emperor Jomei’s first son, Prince Furuhito no Ōe, to succeed the empress. The anti-Soga faction of the court selected Prince Yamashiro once more. Iruka responded to this by attacking Prince Yamashiro and forcing his family to flee their estate. Yamashiro’s aide advised him to escape to the east, but he chose death for his family, explaining that it would help to bring peace to the land and the people. Considering the fact the Soga were powerful enough to convince the court to elect their candidate regardless, Iruka had brought about the end of Shōtoku Taishi’s bloodline for no good reason.

Plotting rebellion

This was the breaking point for a number of members of the anti-Soga faction of the court. A man by the name of Nakatomi no Kamatari decided to take action. He first approached Prince Karu, the empress’ brother, believing he might be able to get him on side. However, a brief conversation with the prince was enough to convince Kamatari that he didn’t have the right credentials. Next on his list was Prince Naka no Ōe, the empress’ son. Kamatari approached him while he was playing with a ball and struck up a conversation. He ticked all the boxes: he was smart, anti-Soga and seemed co-operative. The two struck up a friendship and plotted to overthrow the Soga while studying under Minamibuchi no Shōan, a scholar who had spent time overseas and had an extensive knowledge of the political history of the mainland.

After a while, they had formulated a solid plan. Kamatari found another collaborator, Soga no Kurayamada no Ishikawamaro(possibly the longest name in Japanese history). Although a member of the Soga family, Ishikawamaro wasn’t part of the main branch. Joining Kamatari’s team was his only way of getting rid of his cousin, Iruka, and earning himself a high-ranking position within the court. Kamatari married Prince Naka no Ōe to Ishikawamaro’s daughter to seal the deal.

Iruka’s assassination

The plan was to assassinate Iruka during an official ceremony in which messengers from the three countries that made up what is now the Korean peninsula―Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla―were due to present gifts to the empress. Under normal circumstances, Iruka would have been armed and surrounded by guards, but as a display of trust towards his foreign guests, he opted for minimal security on this occasion. In any case, weapons were banned inside the court; all attending the event were made to relinquish their swords and spears before entering. However, Kamatari had bribed the guards beforehand. Just as the event was about to begin, the guards closed the gates and passed Kamatari a selection of confiscated weapons.

The prince had a spear. Kamatari, a bow and arrow. The two assassins they had hired to help them with the job each brandished swords. They waited in the darkness by the side of the hall for Ishikawamaro to read his speech in front of the empress. That was their cue to attack. However, as the speech began, the assassins suddenly got stage fright. It’s said that they had been so nervous since the time they woke up that morning that they hadn’t been able to eat anything. In an effort to provide themselves with just a little nourishment, they had tried to force rice down their throats with water only to immediately throw it up.

Ishikawamaro began to sweat; his speech was almost over. The attack should have launched by now. His hands began to shake. Iruka became suspicious and asked him what was wrong, to which Ishikawamaro replied that he was simply nervous being in the presence of the empress. Naka no Ōe wasn’t able to wait any longer. He leaped out from his hiding spot and attacked Iruka, giving the assassins the confidence they needed to follow. Together with Kamatari, the four hacked away at the defenceless Iruka, who did his best to appeal to the empress to call off the attack. Naka no Ōe explained to the empress(his mother) that Iruka was plotting to steal the throne. She retreated to the back of the hall, perhaps out of confusion, or perhaps out of shock or repulsion. The four men finished Iruka off, decapitating him and ending his life.

The Soga’s demise

After carrying Iruka’s head outside and leaving it to rot in the rain, Naka no Ōe ran to Asukadera, the oldest temple in the capital, where he amassed a small army. The following day, he marched his men to Emishi’s estate and delivered Iruka’s body. Having received confirmation of his son’s death, Emishi knew he was defeated. His only options were surrender or death. Opting for the latter, he set fire to his land and killed himself, ending the Soga legacy.

Too shocked to be able to continue ruling the country, Empress Kōgyoku attempted to pass the throne to her son, but he refused on the grounds that he didn’t want to give the court the impression that he had killed Iruka solely for personal gain. So instead, the empress passed the throne to her brother, Prince Karu, who ascended as Emperor Kōtoku. As both the Soga family’s chosen candidate and a blood relative to the Soga, Prince Furuhito no Ōe feared for his life. He fled to Yoshino in the south of Yamato province, but Naka no Ōe used this escape as evidence that his brother was plotting a rebellion and had him hunted down and killed, tying up the last of the loose ends and ensuring that no member of the Soga family would ever be able to amass enough power to take control of the court again.

The Taika reforms

In 646, Emperor Kōtoku and Naka no Ōe set to work on Japan’s first documented reform: the Taika reforms―the name being taken from Japan’s first gengō, which was decided upon at the same time. Four major changes were brought about as a result of this reform:

- All land and citizens were designated property of the emperor.

- Governor-type figures known as kuni no miyatsuko(国造)were sent out east to control the rural areas of the country not yet directly under the rule of the court.

- Every citizen over the age of six would be allocated an area of land to cultivate. This land would be returned to the court after a person’s death.

- In exchange for this land, each citizen would be required to pay three forms of annual tax:

- So(租): A land tax equal to 3% of the total amount of rice harvested from the land.

- Yō(庸) : 60 days of service to the court in the form of either protection or carpentry.

- Chō(調) : A residential tax payable in the form of cloth, local delicacies, etc…

In addition to these revisions, a number of personnel changes were made within the court. Three new positions were created: Sadaijin(Minister of the Left), Udaijin(Minister of the Right) and Naishin(Minister of the Interior). These positions were occupied by Abe no Nakamaro, Soga no Kurayamada no Ishikawamaro and Nakatomi no Kamatari respectively. Previously, the three positions had been combined into one role: Ōomi―the role which had been held by the Soga family for generations. By breaking the position up into three smaller positions, Naka no Ōe decreased the likelihood of any one family being able to usurp power from the emperor in the future.

The legacy continues

Having returned power to the Imperial Family, Prince Naka no Ōe went on to support his uncle and later his mother, who took the throne a second time as Empress Saimei, before finally becoming emperor himself in 668. As emperor Tenji, he awarded Nakatomi no Kamatari the Fujiwara kabane. Kamatari’s descendants went on to continue his legacy, supporting emperors for hundreds of years to come and making the Fujiwara one of the most successful families in Japanese history.

Emperor Tenji’s line ended after his death when his younger brother usurped his branch of the Imperial Family’s power and continued the imperial line through his grandson. However, almost a hundred years later, the line would return to Tenji’s branch once more, where it would continue until the present day. Considering the influence that both Emperor Tenji and Fujiwara no Kamatari’s families had on Japan for over 1,000 years, Isshi no hen is, without a doubt, one of the most important events in Japanese history.