The Jōmon era

Welcome to the Jōmon era―the most peaceful era in Japanese history. How do we know it was so peaceful? Well, of all the skeletal remains found from its 14,000-plus-year history, only 1.8% were found to contain evidence of assault―one-fifth of the percentage of similar civilizations from the same time period! For this and many other reasons, it’s relaxing to go back and look at the Jōmon era from time to time(especially after you’ve been studying Sengoku for weeks on end). While the entire era is too large to sum up in one article, I’d like to give you an insight into what the Jōmon era was, who the Jōmon people were and what kind of lifestyle they lived. But first, let’s begin with when the Jōmon era was and how it was discovered.

The discovery of the Jōmon era

While researchers disagree over the precise dates of the Jōmon era, the general consensus is that it began roughly 16,000 years ago and ended around 2,300 years ago, spanning the Mesolithic and Neolithic eras of world history. At the end of the Palaeolithic era, when the last ice age ended, temperatures began to rise. This caused glaciers to melt, which, in turn, caused sea levels to rise 300ft over the course of the following 1,000 years. The rising sea level slowly cut Japan off from the areas of land that are now occupied by Korea and China, allowing the people of this newly-formed island to form a new and unique culture. And while the sea engulfed large areas of fertile soil, it created a coast rich in sea life, offering this new civilisation a fresh and bountiful food source.

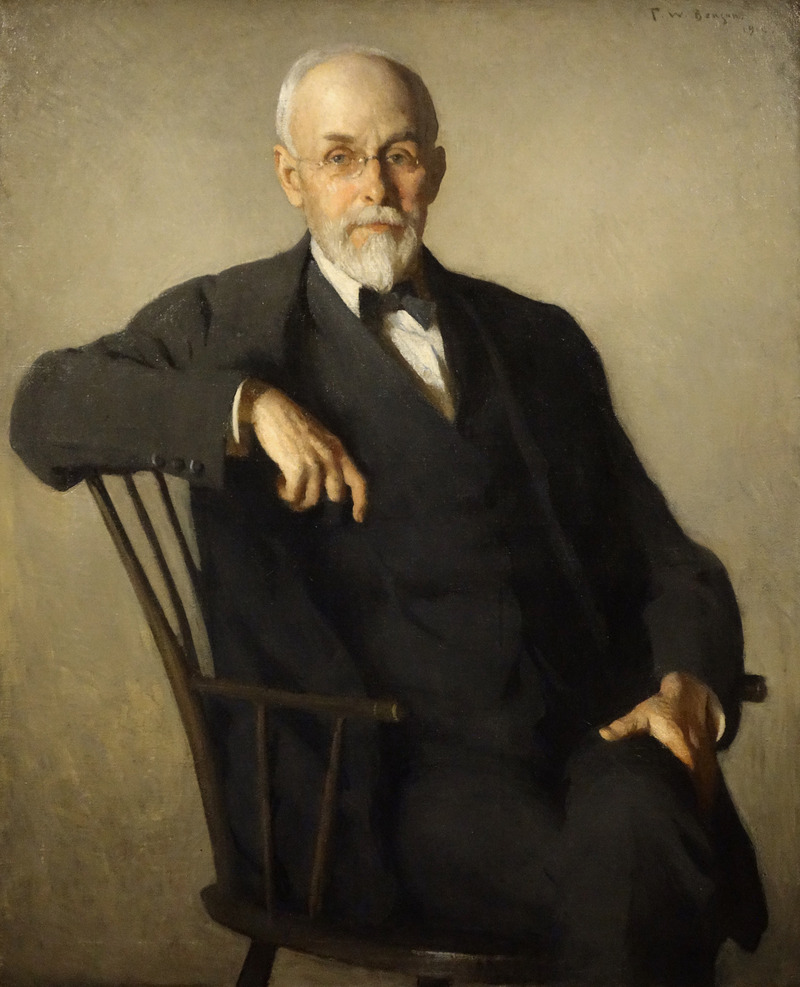

This civilisation was discovered by American zoologist Edward Morse, who was hired by the Meiji government in the late 19th century to help bring Japan into the modern world. Morse stumbled upon a unique-looking shell mound which, when excavated, revealed a form of pottery never before seen by the Japanese people. The exterior of the pottery contained cord-like patterns and was nothing like anything Morse had ever seen in any of his travels. The design was so unique that it was adopted as the name for the era in which the pottery was created: ‘Jōmon'(縄文) which, in English, translates more or less to ‘cord/rope pattern’.

Diet of The Jōmon people

Hunting

As the climate changed, a number of species of plants died out, cutting off food sources for certain large mammals, such as mammoths and buffaloes. These animals tended to migrate to different regions with the changing of the seasons, forcing Jōmon tribes to have to relocate in order to maintain food sources. As animals began to die out due to their own lack of food, the Jōmon people became free from this nomadic lifestyle, affording them the opportunity to create permanent settlements. Smaller animals such as deer and wild boar became predominant on the island. While these animals did not migrate, though, they posed a new problem: they were smaller, faster and more agile than what the tribes had been used to hunting up until that point. The old method of hunting in groups would no longer be effective. And so the Jōmon people devised a solution that would set them apart from their predecessors: the bow and arrow.

Fishing

Along with the bow and arrow, the Jōmon people also developed spears, fishing hooks and harpoons, all made from animal bones and horns. These tools and weapons allowed them to hunt a variety of animals similar to those we eat today. Studies of middens have unearthed the remains of over 60 species of mammals, 350 types of shellfish, 70 varieties of fish and 35 varieties of birds. Clearly, they didn’t go hungry.

Gathering

On the more herbivorous side of their diet, the Jōmon people consumed a large variety of mountain plants and nuts. The latter would go on to become their staple food, and many Jōmon communities would begin to cultivate chestnut and walnut forests towards the end of the era. This diet largely attributed to the rampant tooth decay that existed among the Jōmon people; studies of remains have taught us that 8.2% of the population had tooth decay compared to just 3% in similar civilisations that existed at the same time. Nevertheless, nuts were a sensible choice: they could be stored in the winter, contained a large amount of calories, and their trees made good fuel for fires as well as being strong enough to use in construction.

Seasonal diet

The Jōmon people varied their diet according to the season. In spring, they climbed the mountains and gathered the many plants and vegetables that nature had to offer. They consumed these along with clams taken from the ocean and fish from nearby rivers. Summer diet was less varied; it mainly consisted of the various types of fish that spawned in spring. Autumn was predominantly nuts, a proportion of which they would store to see them through the coming cold. In winter, the lack of plants combined with the fact that the rivers often froze over left them no choice but to hunt.

Winter was the perfect season for hunting; the lack of leaves on trees and bushes provided greater visibility, allowing hunters to locate their prey more easily. They used traps such as pitfalls to catch their prey, and they hunted together with dogs, which they presumably used to chase the animals into the traps. The coldness of winter was also beneficial for preserving meat, meaning that less of it went to waste.

Lifestyle of The Jōmon people

The Jōmon people lived in small villages consisting on average of three pit dwellings surrounding a large communal area, which sometimes contained storage facilities or communal meeting halls. These villages were typically located within 3 miles of hunting or fishing grounds. Presumably three generations of a family would live in one village, with parents raising their children in one dwelling while their siblings and parents lived in the others.

Pit dwellings

The dwellings were created by first digging a large hole in the ground, into which four pillars were erected. This formed the main structure of the dwelling. The pillars were supported by diagonal beams and rafters, which gave the dwelling its shape. Once construction was complete, the exterior structure would be thatched with reeds and tree bark to provide warmth and protection from the rain. In colder regions, the exterior would be covered with soil, allowing the roof segment to sprout grass and blend into the surrounding environment, turning the dwelling into a makeshift cave of sorts.

The internal area was typically 200 square feet wide. A hearth was placed in the centre. During the day this would be used for cooking, and in the evening it would continue burning to provide warmth and light. Next to the hearth, deep pots containing water and baskets of nuts may have been placed. The Jōmon people had a variety of pots and cooking utensils, many of which have been unearthed in recognisable condition due to the fact the pots were strengthened with plant fibres and the utensils were protected with lacquer. This suggests that the Jōmon people took great pride in their work and valued their creations. Hunting and fishing tools would have most likely been propped up against the walls, and the earthen floors were possibly covered in woven mats or animal furs.

Communities

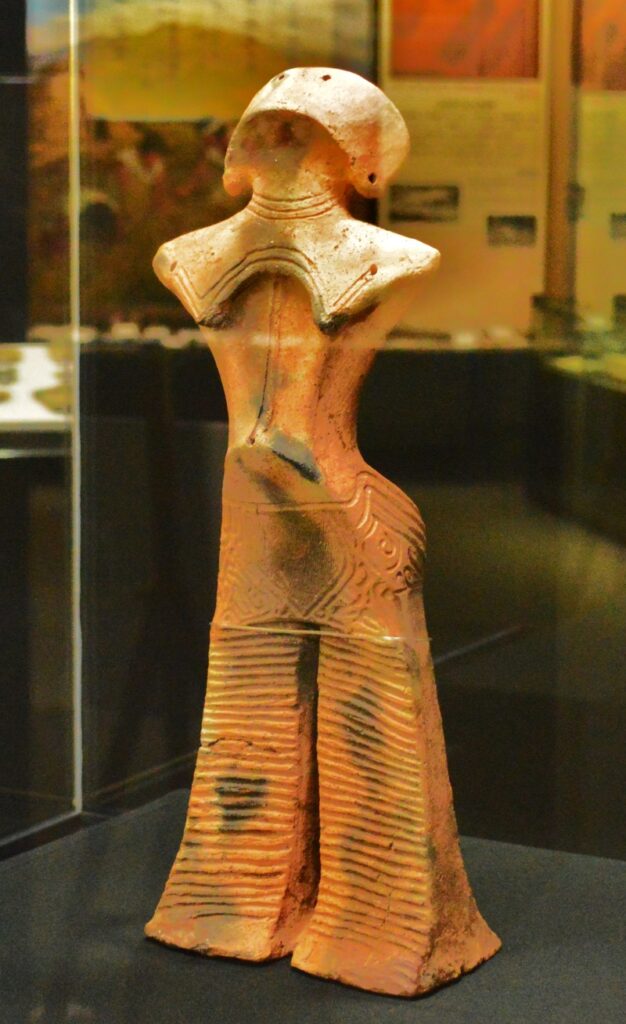

As villages grew in size and began to form connections with one another, people would have begun to intermingle and create small communities. At the centre of these communities were shamans, who presumably guided the members spiritually and performed religious rituals. A number of ritualistic tools and props have been unearthed, including stone rods―which are presumed to represent men―and clay figures known as dogū(土偶)―which are presumed to represent women. Dogū in particular spark a great deal of interest among researchers, historians and history buffs all over the country. Various theories as to their purpose and evolution have been proposed, but none have been(or possibly even can be) definitively proven. Below is a selection of some of the most famous dogū discovered to date.

Customs

Shamans may also have been responsible for performing tooth ablation―a rite of passage faced by young Jōmon when they reached adulthood. 1-3 teeth would be hammered out using a long wooden stake in a procedure too painful to even imagine, presumably without the use of any kind of anaesthesia(they may have had access to certain plants that contain numbing agents, but no one knows for sure). It’s entirely possible that rather than the loss of teeth, the endurance of the pain itself was the rite of passage(or it’s possible they just wanted to get rid of the teeth that were most susceptible to the inevitable tooth decay they’d face from binging on nuts). The teeth removed varied from region to region, and, in some cases, denoted class. A number of skulls unearthed have been identified as shamans due to the ages at which their owners died and the fact that they had more teeth removed than other skulls found in the same areas.

The end of the Jōmon era

Around 2,500 years ago, the temperature dropped significantly, delivering a blow to fishing regions. The population was also increasing, creating a greater need for more sustainable and bountiful food sources. More and more people began to turn to rice cultivation as a means of obtaining a stable food supply. It’s estimated that the population at the start of the Jōmon era was 20,000. At its peak, this number soared to 260,000. However, towards the end of the era, the lack of food caused the population to plummet to 80,000. Rice cultivation required the cooperation of a large number of people. With the dwindling population, the Jōmon people were unlikely to thrive anytime in the near future. However, hope was not lost; new races of people were about to venture their way to the island in order to escape war and persecution in their own lands, and they would bring with them the tools, knowledge and manpower necessary to produce a sustainable rice supply. The Yayoi era was about to begin.