The Ōtsu Incident

History is so riddled with events that not all of them get the attention they deserve. The Ōtsu Incident is a prime example. At a glance, an attack on the heir to the Russian throne may look like something that would have at least a page dedicated to it in school textbooks. Its poor timing, however, would earn it nothing more than a footnote. Having occurred on May 11, 1891, right in the middle of the Meiji era, sandwiched in between the establishment of the Japanese constitution and the Sino-Japanese war, the Ōtsu Incident is enormously overshadowed.

When you consider the impact it would eventually have on the Japanese legal system as well as how it would affect the way Japan was viewed by the major global powers of the time, however, the Ōtsu Incident is far more significant than history gives it credit for. It can even be argued that it forced Japan to take the first necessary step towards being viewed as a developed country. Let’s finally give this underrated incident the attention it deserves.

The Ōtsu Incident

On their way back home from attending a ceremony marking the commencement of the construction of the Siberian railway, Tsarevich Nikolai and his cousin, Prince George of Greece, decided to take a tour of Japan. Nikolai was apparently a huge fan of Japan and had wanted to visit the country for a long time. During this short vacation, he viewed numerous geisha performances, attended the burning of the five mountains of Kyōto and even got a dragon tattoo! He began his journey with a tour of Kagoshima and Nagasaki before travelling by ship to Kōbe, making his way to Kyōto, then taking a trip around Lake Biwa in Ōtsu City on his way to Yokohama and Tōkyō.

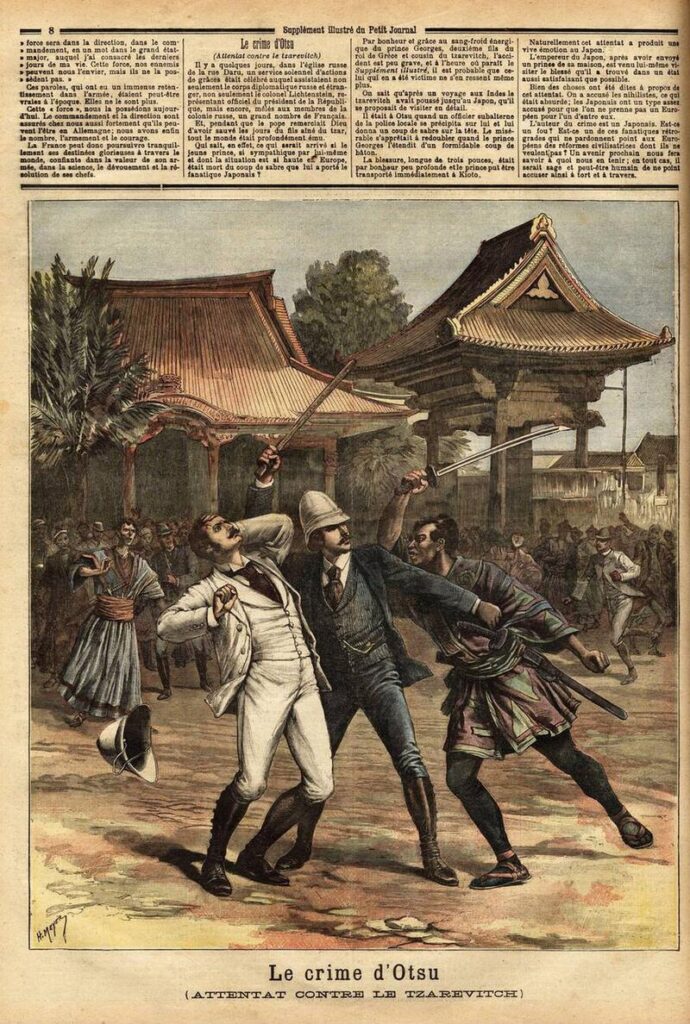

However, his trip was cut short when he was suddenly attacked on his way back towards Kōbe while being carried out of Ōtsu City by rickshaw. Police officers had been stationed at 60 ft intervals along the long road. Ordinarily, this would have been more than enough to secure the safety of the tsarevich and his entourage, but no one could have predicted that a police officer himself would launch an attack!

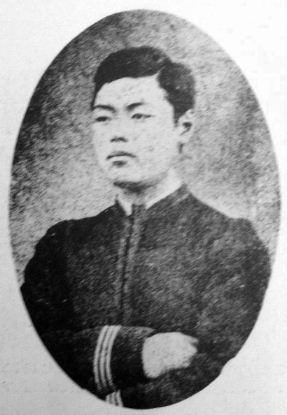

Tsuda Sanzō

36-year-old Tsuda Sanzō drew his saber without warning and lunged at the tsarevich, slicing the blade downwards across his forehead, leaving a deep 3-inch-long cut. Nikolai stumbled out of the rickshaw and did his best to run while being chased by the maniacal Tsuda, whose attempts at a follow-up attack were thwarted by Prince George, who struck the assailant in the back with a bamboo cane he had bought as a souvenir. The rickshaw attendant grabbed Tsuda’s legs and pulled him to the ground, forcing him to drop his weapon. Prince George’s attendant picked up the fallen saber and sliced Tsuda’s neck before two police officers arrived to apprehend him.

The young tsarevich escaped with minor injuries(although if you consider how he later died, it would probably have been better for him if the assassination attempt had succeeded!). He received swift treatment after a hasty return to Kyōto, and his condition was stable. The impending diplomatic crisis had Japan panicked though; its fledgling government had only been formed six years prior, and not one of its members had any experience of dealing with such a volatile international issue. The first and most obvious step had to be a visit from the emperor.

Emperor Meiji

The emperor arrived two days after the Ōtsu Incident and visited Nikolai, who was recovering in Kyōto Hotel. He apologised profusely for what had happened, but Nikolai was surprisingly relaxed about the entire affair, stating that every country has fanatics and that one man’s actions wouldn’t scar his view of the Japanese nation. As it would be the tsarevich’s birthday in five days, the emperor offered to throw him a banquet, but Nikolai refused, instead offering to host a banquet of his own for the emperor aboard his ship the day before his planned departure.

Many officials advised against the emperor attending, believing it may be an attempt to kidnap him and bring him back to Russia, but the emperor decided to take the risk. In the end, the banquet turned out to be nothing more than a banquet; all involved had a good time, and the emperor returned safely to Tōkyō. Relieved, the Japanese government sent a message to the Russian government, informing them that they intended to send an envoy to offer an official apology, but the Romanovs replied saying that wouldn’t be necessary; they were more than happy with the way Japan had handled the situation, and they didn’t expect any further action.

The aftermath

Mass hysteria

As far as the emperor and the government were concerned, the situation was resolved. However, mass panic began to spread among the people. According to Tsuda, the reason for his attack was the belief that the tsarevich’s true purpose for coming to Japan was to scout the land in preparation for an invasion. Russia had been caught sniffing around certain islands to the west of Japan several times over the course of the previous 20 years, and the newspapers hadn’t wasted the opportunity to exaggerate the situation to the point of spreading fear and paranoia across the general populace. Now, once again, the newspapers escalated the situation by implying that Russia was likely to attack Japan in retaliation to the assault on their future leader.

It had only been two years since the establishment of the Japanese constitution, which granted the emperor undisputed authority over the government, the army and the people. In addition, the educational reform that had been carried out the previous year placed a large emphasis on loyalty to the emperor. As a result, the Japanese people were extremely patriotic, to the extent they valued their country over their own lives. Schools closed for days. Temples and shrines prayed for the safety of the tsarevich. Over 10,000 people sent telegrams to Russia, conveying their wishes for Nikolai’s recovery. One town in Yamagata went so far as to ban any of its citizens with the surname ‘Tsuda’ from naming their future children ‘Sanzō’. The most extreme example of national repentance, though, was 27-year-old Hatakeyamo Yūko, who killed herself by slitting her throat with a razor blade in front of Kyōto’s Prefectural Office.

Tsuda’s sentencing

While all this was going on, the government was divided over how to deal with Tsuda. Prime Minister Matsukata Masayoshi and the majority of government officials pushed for the death penalty, assuming it would be in line with the wishes of the Russian royal family. However, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Kojima Korekata threw a spanner in the works.

If Tsuda were to be given the death sentence, he would have to be charged under Article 116 of the penal code, which stated that any form of assault on a member of the Imperial Family was punishable by death. Kojima argued that since Tsarevich Nikolai was not a member of the Japanese Imperial Family, Article 116 did not apply. As no laws regarding assault on a member of a foreign royal family existed at the time, Kojima informed the government that Tsuda would have to be charged under Article 292, which dealt with the attempted murder of a member of the general public and carried a sentence of life imprisonment.

The Separation of Powers

Matsukata sent Saigō Tsugumichi, the minister of home affairs; and Yamada Akiyoshi, the minister of justice, to convince Kojima to change his mind. However, even after hours of tiring debate, Kojima stood firm. The two ministers went so far as to bluff that they had an imperial decree commanding that Tsuda be tried under Article 116, but Kojima wasn’t stupid enough to fall for it. Of course he understood their reason for pushing the death penalty, but to Kojima, the separation of government and court and the protection of Japanese law took precedence over maintaining relations with Russia. In the end, he got his way: on May 27, Tsuda was sentenced to life imprisonment under Article 292.

Four months into his incarceration, Tsuda died of pneumonia. Various rumours formed surrounding his death. Some believed he really committed suicide; some believed the government had him assassinated. Whatever the case, pneumonia remained the official story, and no evidence would ever surface to suggest otherwise.

Conclusion

All in all, everything worked out very well for Japan. The swift action taken by the government, the emperor and the people went a long way towards strengthening relations with Russia, and, as a bonus, the fact that Japan chose to keep political influence out of the court persuaded America and Europe that it was no longer a developing country but rather a constitutional state ready to be a part of the global community. As a result, two years later, Japan negotiated a new trade agreement with Britain—a fair agreement that benefited both countries equally. Considering the fact Japan had made several unsuccessful attempts to form this agreement over the course of the previous 40 years, the outcome of the Ōtsu Incident unarguably had a major effect on the course of what was yet to come for the newly-developed nation.

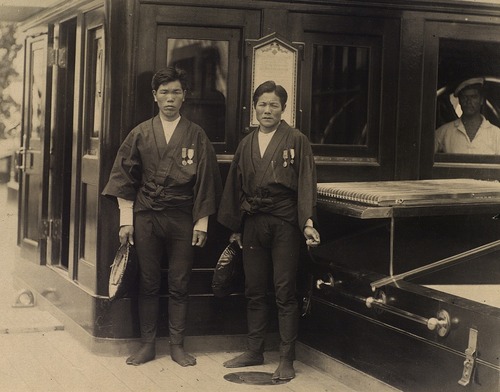

As for the two rickshaw attendants who helped subdue Tsuda, they each received a sum of ¥2,500 from the Russian royal family(an amount equivalent to roughly ¥11,000,000 in modern money), in addition to an annuity of ¥1,000. The Japanese government awarded each man the Order of the Rising Sun medal and a ¥36 pension. Both men were considered heroes by the nation.

Tsuda, needless to say, was considered a traitor in the eyes of the people. Ironically, however, just 13 years later, when Japan and Russia went to war, the situation did a complete 180, with Tsuda being hailed a hero and the poor rickshaw attendants being branded traitors and having their Russian annuity annulled(although to be fair to Russia, they never cancelled it; the Japanese government simply refused to accept it). I suppose the true moral of the story is that people are easily swayed by the media.