The Rice Riots

Japan is no stranger to riots. The Edo shōgunate’s biggest headache was trying to keep the country’s economy stable through numerous challenges, including droughts brought about by earthquakes and volcanoes, and a particular shōgun who prioritised dogs over his own people. When the shōgunate failed to stabilise the economy, farmers would riot. And while these riots tended to die down quickly, the shōgunate realised that mob mentality can cause people to do a great deal of damage in a short amount of time. The greatest example of this was in 1837, when an official in Ōsaka led the people in a rebellion against the shōgunate, who had made it abundantly clear that they prioritised rank and tradition over ensuring the populace had enough to eat. While this rebellion ultimately failed, it inspired further riots, which eventually—albeit indirectly—led to the downfall of the shōgunate.

Having witnessed the mistakes of their predecessors, the Meiji government knew all too well what would happen if they didn’t create a system that, at the very least, kept the people satisfied. Much as they endeavoured to create this system though, in 1918, a number of converging factors, some beyond the government’s control, led to Japan’s longest and most widespread series of riots. Let’s take a look at the reasons why the rice riots happened, how they played out and their consequences.

Reasons

In the early 20th century, despite the many foods introduced from other countries, Japan’s rice-eating culture prevailed. Many found beef and pork to be too fatty and oily, so they consumed excessive amounts of rice in order to get their daily intake of protein and carbs. It wasn’t unusual for workers to eat as much as 3.3 lbs of rice a day! People spent on average 60% of their income on food—almost three times the amount they spend today—so even the slightest of fluctuations in the price of rice had the potential to put an enormous strain on their wallets.

Rice first started to go up in price during the First World War, when Japan’s export industry began to boom. Since the countries that normally produced fabrics and metals were now at war, not only did they lose the manpower and resources necessary to meet global demand, but they themselves were in dire need of clothing and weapons. Japan’s involvement in the war being minimal, they were able to fill this gap. They supplied Europe, Asia and Africa with silk threads, cotton, chemicals, metals, machines and ships, amassing a combined profit the likes of which the country had never seen.

The problem was, in order to meet this growing demand, factories needed an ever-increasing number of workers. The only way to procure this workforce was to lure workers from the country’s most prominent industry: agriculture. Between 1913 and 1920, the number of farmers dropped by 700,000, putting a severe strain on Japan’s rice cultivation. To make matters worse, farmers tended to live on a diet of varied cereals. As they moved to the cities and into the factories, they switched to a strict rice diet, increasing the country’s demand.

To make matters worse still, in 1917, Japan was called on by America and Europe to lead troops into Russia in order to rescue Czech soldiers who were being held prisoner by the Soviets. Merchants knew the government would need an enormous supply of rice to feed the soldiers, so they began to buy in bulk with a view to selling their stocks back to the government at inflated prices. All this coincided with an unusually cold summer that produced a poor harvest, decreasing the country’s rice supply further.

The outbreak

For years, the price of rice had remained more or less stable, fluctuating between 10 and 20 yen per 330lbs. However, as rice traders and speculators began to buy up more and more rice, depleting the supplies usually available for distribution around the country, the price rose sharply. By August 1, it had reached a whopping 35 yen, already expensive enough to impoverish most of the nation. But that was just the start; a mere five days later, it rose to 40 yen. By August 9, it had soared to a record high of 50 yen and still showed no signs of slowing down. What this meant for the common man was that a 3.3 lbs bag of rice that normally cost just 0.34 yen now cost 0.6 yen. Considering the average worker’s monthly wage at the time was 15-25 yen, this increase put a major strain on households.

The previous year, the prime minister had issued a law banning companies from buying up rice and distributors from refusing to sell rice, but it had had no effect. Large trading firms helped out by importing rice from other countries, but this too did nothing to bring about deflation.

And then one day in a quiet little fishing town in Toyama, a group of 25 or so women gathered together to discuss the situation. They’d heard a rumour that a large supply of rice was due to be shipped out from the local area and worried that this would affect local prices further. Toyama’s fishing industry was poor. People were forced to survive on rice porridge, but more and more rice was being exported to major cities where it could fetch a better rate, driving the price up locally and putting further strain on Toyama’s citizens.

The group collectively decided to do something about it. And so they appealed to the local rice wholesalers to keep the rice in Toyama and sell it at more reasonable prices. The wholesalers refused, and the women went home dismayed. That was the end of it. However… The following day, the headlines in the local papers read ‘Housewife uprising’ and ‘Women revolt’, escalating the situation to the point where just four days later, 200 angry citizens stormed the city office.

This incident ended peacefully with the police convincing the group to return to their homes, but a large number continued the fight, going around the local rice dealers and appealing their situation. When their words inevitably fell on deaf ears, more and more people joined the cause. On August 3, 3,200 of them petitioned the wealthiest rice merchants to cease the transfer of rice out of Toyama. Over the following three days, a further 800 people signed the petition. When they realised it was having no effect, they resorted to threats to get the dealers to sell them rice at 0.35 yen per 3.3 lbs bag rather than the market value of 0.4 – 0.5 yen.

The highlights

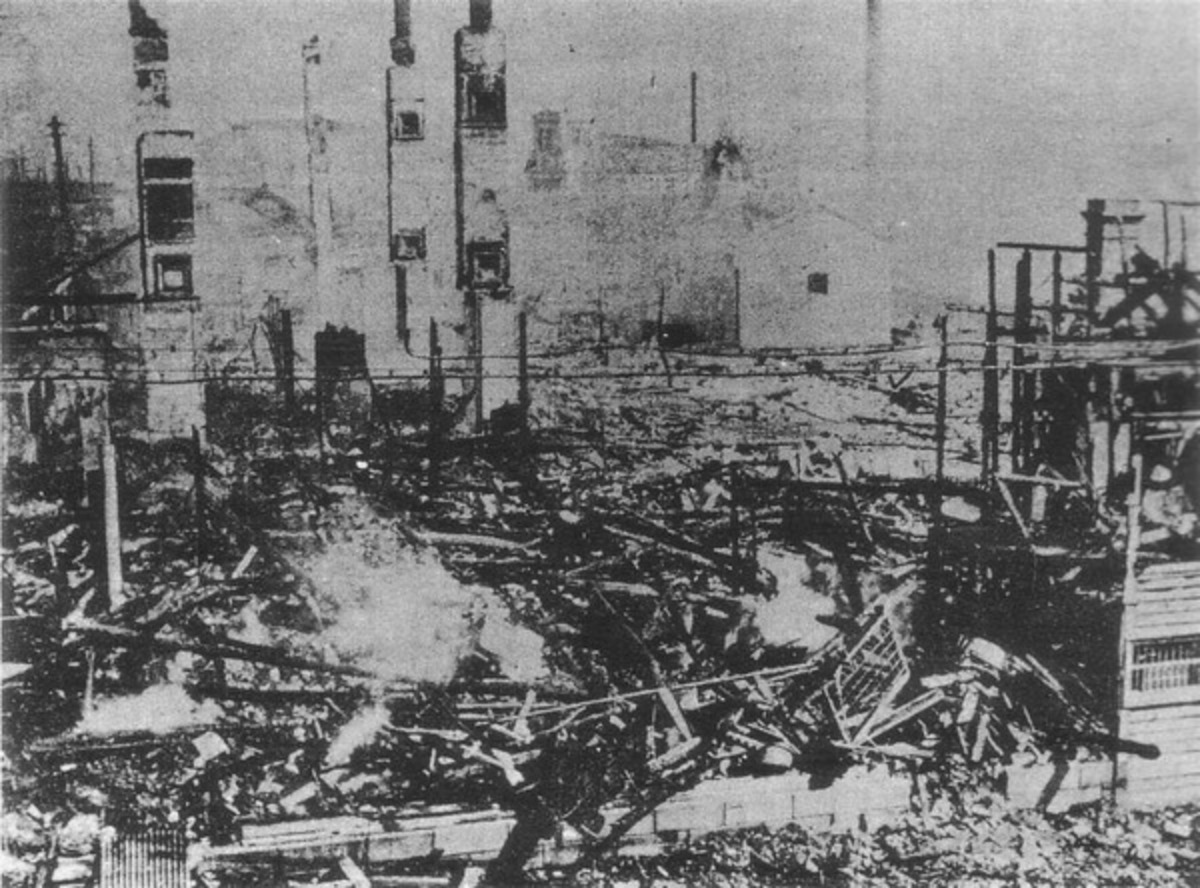

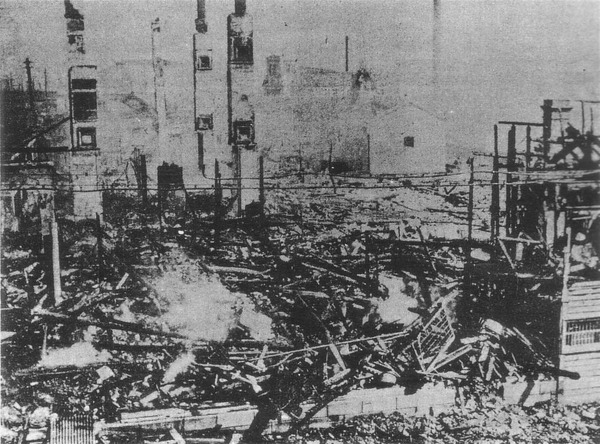

On August 10, the Asahi Shimbun newspaper posted an article containing fabricated reports that the Suzuki Company had started charging one yen commission on all rice transactions of 330 lbs. Later that day, an angry mob burned down the company’s headquarters. What had started as a series of peaceful petitions for cheaper rice sales and distribution curbs had now developed into demands for donations and vandalism.

On August 13, 2,000 people showed up for a political speech scheduled to be performed at an outdoor concert venue in Tōkyō. Security was tight, with over 200 police officers surrounding the area. When a number of the attendees suddenly stormed the stage, the police intervened. This awarded the rest of the mob the opportunity to split into three groups and escape the area to wreck Joker-level havoc on the city. Their repertoire of destruction included throwing rocks at shop windows and police stations, damaging cars and trains, storming the Yoshiwara pleasure district, and starting fires. One of the groups even marched to Asakusa and invaded the head office of a major rice distributor, threatening the owner into selling them rice at cheaper prices.

On August 15, the army was deployed. In the space of a day they arrested 299 people, but still the situation continued to escalate. When people realised they could force distributors to sell at lower prices, word spread around towns, villages and cities all over the country. At their peak, the riots spread to 369 cities across 41 of Japan’s 47 prefectures and involved several million people. Over 100,000 soldiers were deployed across 26 of these prefectures, but it did little to quell the violence. In some cases, the police turned a blind eye to the chaos, silently supporting the rioters. After all, the rice inflation affected them as much as it did anyone else.

In Fukuoka and Kumamoto, miners were furious about the fact that even though both rice and coal prices were rising, their salaries remained unchanged. At Mineji Coal Mine, 100 miners destroyed the company store and made away with all the barrels of sake. When the police arrived on the scene, the miners attacked them with lit dynamite. Eventually, the army showed up. Some of the miners climbed electricity pylons wearing just fundoshi, lit sticks of dynamite with cigarettes and threw them down at the police and soldiers. They were shot dead.

Although the majority of these acts did little to alter the situation, in a small handful of cases, they did have an effect: just one day after experiencing an attack, a certain coal mine decided to double its workers’ salaries.

Statistics

The riots lasted 50 days. 30 people were killed and 25,000 arrested. Of those, 8,253 were prosecuted and 7,786 were tried in court. 59 were sentenced to over ten years imprisonment; 12 were sentenced to life imprisonment; 2 were given the death penalty for rousing masses in Wakayama.

The aftermath

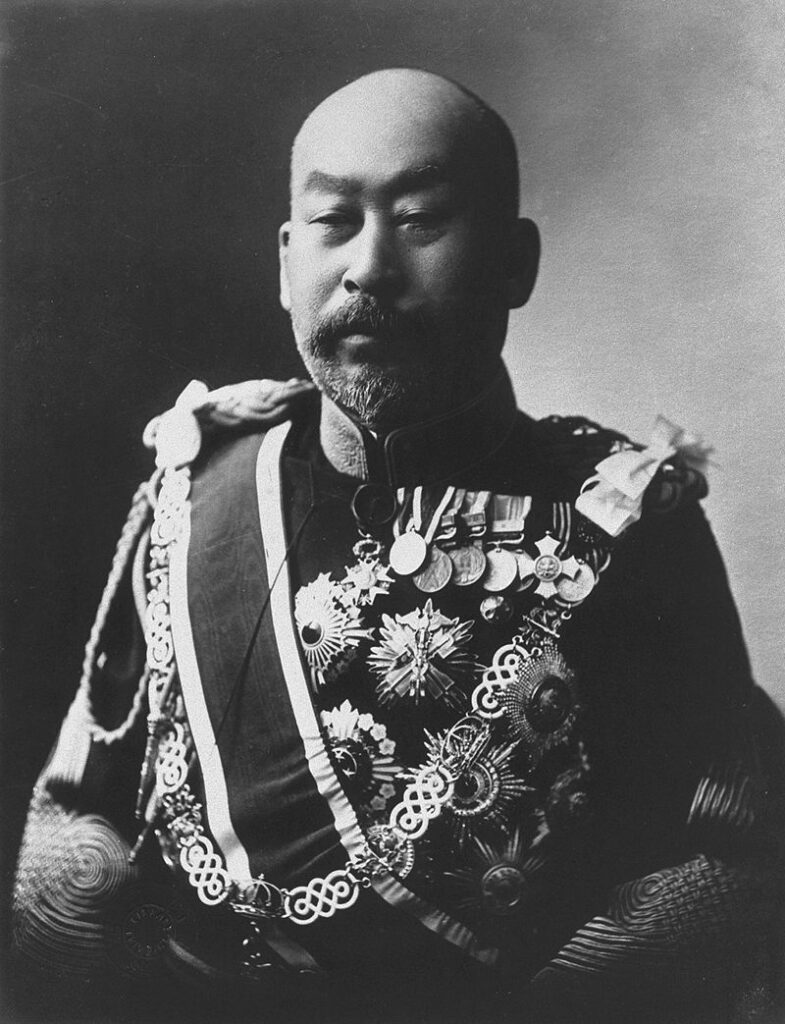

Rice prices continued to rise until 1920 before finally settling. However, as salaries also began to increase, there was never a repeat of the rice riots. Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake took full responsibility. He and the members of his cabinet resigned on September 20. Some say this was the real target of the newspapers, who sparked the entire affair with their exaggerations and fake news.

Terauchi was replaced with Hara Takashi, Japan’s first prime minister to have been awarded the title without ever having received a noble rank. The people were delighted to finally have a leader they could relate to—someone with a background similar to theirs. However, just three years later, he was assassinated by a train driver who opposed his policies.

The riots gave the people the courage to conduct protests against the government. In 1919, they succeeded in getting the voting rights laws changed so that while originally only men over the age of 25 who paid more than 15 yen per year in tax had the right to vote, now any man who paid just three yen in tax was eligible. This raised the percentage of the voting population from 1.1% to 5.5%. Finally, in 1925, the tax restrictions were removed entirely, awarding 20.8% of the population the right to vote and any man over the age of 30 the right to run for office. It would take a further 25 years before women could receive these same conditions though.

Conclusion

If history has taught us anything at all that we can apply in this modern age, it’s taught us that when backed into a corner, the oppressed masses can grow far stronger than those who control their resources. With inflation on the rise and housing prices becoming exponentially more expensive, it may not be long before we see something akin to the rice riots in our own society.