The Seven Great Temples of Nara

Today we’re going to be taking a look at the Seven Great Temples of Nara—the seven temples considered to have held the greatest amount of influence in Nara prefecture throughout history. Having lived in Nara since 2006, this is a topic close to my heart. I’ve visited all the temples I’m going to be describing in this article multiple times each, but I never get tired of walking around their grounds, enjoying the serenity that envelops their peaceful gardens, their beautiful and understated architectural style unique to Japanese Buddhism, and, of course, their mind blowingly-detailed statues.

Until 2015 or so, Nara was unknown to most of the world. Now, however, tourists flock from all corners of the earth to see its infamous deer park and bask in its tranquil atmosphere. Before we dive into the main content of this article though, let’s first take a look at Nara’s history.

The History of Nara

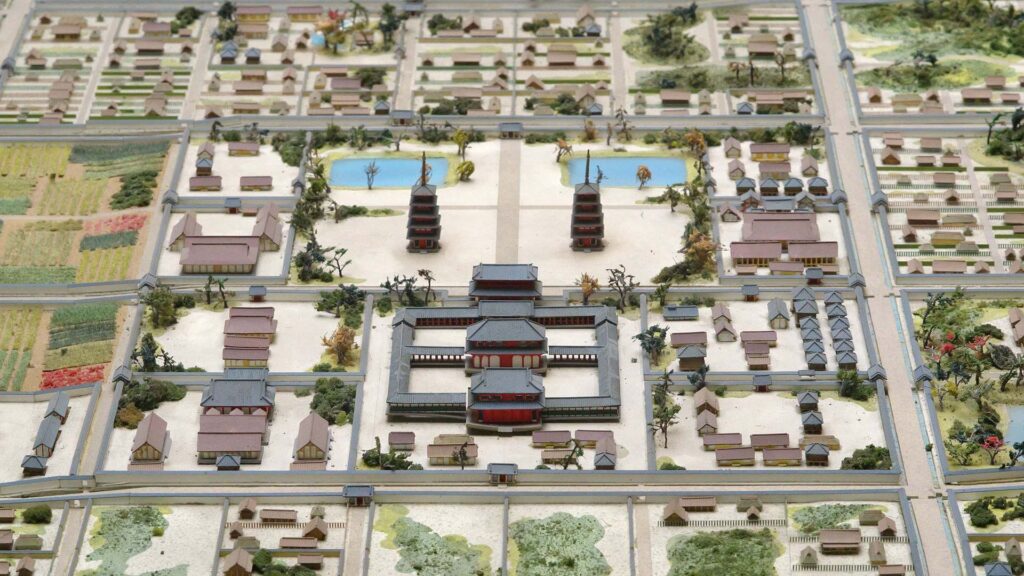

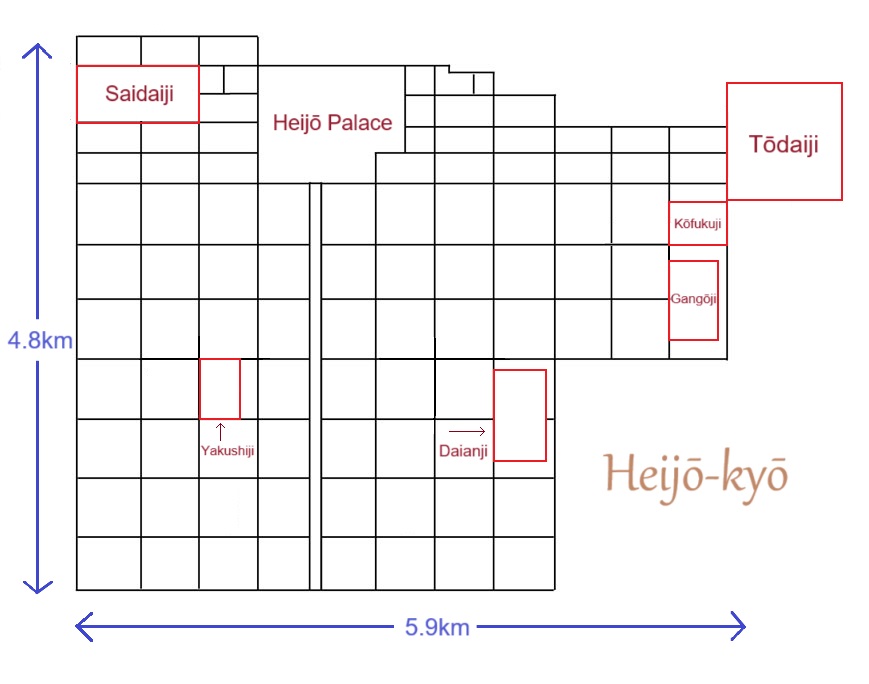

Japan’s capital was moved many times throughout history before it finally settled in Heian-kyō(Kyōto) in the year 794. For brief periods, Ōsaka, Shiga and various locations around the south of Nara played host to the court, but between the years 710 and 784, the role belonged to the northern area of Nara which is now a part of Nara city. At the time, it was known as Heijō-kyō(平城京), ‘Heijō’ being the name of the area and ‘kyō’ meaning capital.

During its time spent as the capital, a large number of temple complexes were constructed in Heijō-kyō, in which the six Buddhist sects of the time not only practiced their beliefs but also studied an all-encompassing range of subjects, including art, poetry, philosophy, theology and even science. Temples in the Nara era were not merely houses of worship; they were schools, and the priests who lived within them, scholars.

Of the many temples constructed in the Nara era, seven became widely known as the most powerful temples of Nara. All seven remain today and continue to practice Buddhism, although in some cases their sects changed over the years. As well as being home to thousands of parishioners, each can be entered and explored for a small fee, and services such as lectures and sutra writing sessions are available to both tourists and the general public. Let’s take a look at each of these temples in the order in which they were established.

Gangōji

Established: late 6th century

Sect: Shingon Ritsu

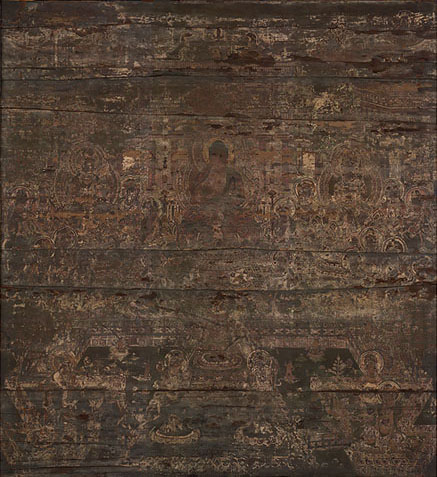

Main objects of worship: Chikō’s Mandala, Eleven-faced Kannon, Kokūzō Bosatsu

Original Area: 23.7 acres

In the mid-6th century, when Buddhism was first introduced to Japan, the two most powerful families in the court had a disagreement over whether or not to allow the religion into the country. The Soga believed that by accepting it, the court would be able to create stronger ties with the mainland; the Mononobe argued that it would anger the Shintō gods. This led to decades of fighting which eventually resulted in the destruction of the Mononobe and the unrivalled rule of the Soga. The family’s leader, Soga no Umako, set to work building Hōkōji, currently known as Asuka-dera—the first fully-fledged Buddhist temple in the capital of Asuka.

When the capital moved to Heijō, the court rebuilt Hōkōji and changed its name to Gangōji. Asuka-dera remained in its original location, however, creating a unique situation in which two versions of the same temple existed in different locations.

Despite Asuka-dera’s continuing authority over Asuka, Gangōji slowly waned in power over the years, unable to maintain the same level of support as other temples that were established around the same time. By 1035, its grounds were so weather-stormed, they were almost unrecognisable as a Buddhist complex. Eventually, Gangōji was forced to split into three smaller temples in order to survive.

Centuries later, Tsujimura Yasuen, who became the chief priest in 1962, established the Gangōji Institute for Research of Cultural Property. Improvements and repairs to the three areas’ facilities were conducted gradually over the following years, including the completion of a storage room in which temple treasures could be exhibited. Now restored to its former glory, the temple and its grounds welcome visitors from all over Japan, and, more recently, from all over the globe. ¥500 gets you access to all temple areas and the main hall. (All prices listed on this page are valid for 2025.)

Hōryūji

Established: 607

Sect: Shōtoku

Main object of worship: Shaka triad

Original Area: 46.2 acres

After defeating the Mononobe, Soga no Umako’s great-nephew, Shōtoku Taishi—one of the first active proponents of Buddhism—built Japan’s first state-sponsored temple: Shitennōji. Several years later, he relocated to an area of Nara called Ikaruga, located at the midway point between Shitennōji and the palace in Asuka. From there, he was able to keep a watch over both while he conducted politics from his newly-built offices.

Being the most devout Buddhist at the time, it was only natural that he construct a temple on his new land. He named this temple Hōryūji, and it remains today as the oldest wooden structure in the world. Although it is believed that the temple never once burned down throughout the many centuries that have passed since its construction, a section in Japan’s oldest history text, the Nihonshoki, states that it burned down in 670. With no other sources to back this claim up, it was dismissed throughout the ages. However, since 1887, the theory that the temple was rebuilt in the late 7th century has been growing in support. Whichever the case, the temple remains the world’s oldest wooden structure.

Hōryūji can be entered today for a relatively high fee of ¥2,000. Considering the fact that the other temples listed in this article cost an average of ¥800 to enter, on the surface, a trip to Hōryūji might seem expensive. However, when you consider the fact that the ticket grants you access to three separate temple complexes containing a plethora of some of the oldest and most unique Buddhist statues from the Asuka era, and, on top of that, entry to a private museum, it’s well worth a visit!

Daianji

Established: 645

Sect: Shingon

Main object of worship: Eleven-faced Kannon

Original Area: 44.4 acres

In the early-7th century, Shōtoku Taishi suggested to his cousin, Prince Tamura, that they establish a court-sponsored temple in Asuka. Years later, Prince Tamura took the throne as Emperor Jomei and realised his cousin’s dream by constructing a temple along the banks of the Kudara River. Taking the name of its location, the temple became known as Kudara-Ōdera.

In 673, Kudara-Ōdera was moved to a new location in Takaichi-gun, where it was renamed Takaichi-Ōdera before being renamed a second time several years later as Daikan-Ōdera. When the temple was moved to its final location in Heijō, it received its current name of Daianji. As it was located in the south of the capital, it also received the nickname Nandaiji(南大寺), meaning the Southern Great Temple. This is in contrast to two temples we’ll be looking at further on in this article: Tōdaiji(東大寺) and Saidaiji(西大寺), which mean the Eastern and Western Great Temples respectively.

Daianji is currently famous as a temple where people can pray for recovery from cancer. The grounds can be roamed for free, and the main hall can be entered for ¥600.

Kōfukuji

Established: 669

Sect: Hossō

Main object of worship: Shaka Nyorai

Original Area: 29.6 acres

After helping conduct Japan’s first political reform in 646, Nakatomi no Kamatari earned his place by Emperor Tenji’s side. In the emperor’s final year, he awarded Kamatari the ‘Fujiwara’ kabane, a name his family would continue to use for hundreds of years as they effectively ran the court.

In 669, when Kamatari fell ill, his wife, Kagami no Ōkimi, built a temple to pray for her husband’s recovery. The temple was first built in Kyōto’s Yamashina ward and was named Yamashina-dera. Sadly, it wasn’t able to fulfill its purpose as Kamatari died that same year.

The rise of Kōfukuji

The temple moved with the capital, first to Fujiwara in the south of Nara prefecture, where it was renamed Umayasaka-dera, and later to Heijō, where it received its current name of Kōfukuji. Backed by the Fujiwara family, Kōfukuji grew into one of the three most powerful temples of the Heian era, along with Enryakuji, which belonged to the Tendai sect, and Onjōji, which belonged to the Tendai Jimon sect.

In 1181, most of the complex burned down at the hands of the Taira when war broke out between the Taira and the Minamoto. The buildings were quickly rebuilt, and Kōfukuji was reborn stronger than ever, forming alliances with local samurai clans in order to remain the dominant power in its province. This was no small feat; Kōfukuji was perhaps the only temple in the country that succeeded in preventing even the shugo from usurping its power throughout the entirety of the Sengoku era.

The Fall of Kōfukuji

It wasn’t until the Meiji government regained control of the country from the shōgunate that Kōfukuji’s power finally began to wane. With Shintō having been selected as Japan’s official religion, support declined to the point where the temple’s monks were forced to either move to other temples or convert to Shintō and find work at the nearby Kasuga shrine, which, until around the same time, had also been under the jurisdiction of the Fujiwara family.

By 1880, Kōfukuji was nothing more than a husk. With its land having been returned to the government, talk of auctioning off the remaining buildings began. At one point, its infamous five-storied pagoda was on the brink of being sold to a private buyer who intended to disassemble the tower and sell the wood for a profit. Luckily, Nara residents petitioned to put a stop to this, arguing that if the temple complex was cleaned up and restored, it could serve to bring tourists into the area. In the end, the pagoda and several other buildings were kept. The earthen wall surrounding Kōfukuji’s land was removed, and trees were planted in its place. They currently encompass the western border of Nara Park.

In 2018, Kōfukuji’s main hall, the Central Golden Hall, was rebuilt. Entry costs ¥500. Entry to the Eastern Hall costs ¥300. You can also enter the Treasure Hall, where Kōfukuji’s oldest and most famous statues are exhibited, for ¥700. Alternatively, you can purchase a ¥900 pass that grants you entry to both the Eastern Hall and the Treasure Hall. Personally, I’ve only ever visited the Treasure Hall. I don’t know how impressive the other buildings are, but the Treasure Hall alone is worth the visit. Among its highlights are a 16 ft tall Thousand-Armed Kannon statue and the infamous dry-lacquer statues of the eight legions, which are all national treasures. The Ashura statue is particularly famous and is often sent to museums around the country to allow everyone the chance to view it.

Yakushiji

Established: 680

Sect: Hossō

Main object of worship: Yakushi triad

Original Area: 19.7 acres

When Emperor Tenji died in 672, his brother, Prince Ōama, waged a war against his son, killed him and usurped the throne. As Emperor Tenmu, he went on to become one of the most accomplished emperors of all history, changing the title of emperor from ‘ōkimi'(大王) to ‘tennō’’(天皇), the name of the country to ‘Hi no Moto ‘(日本), ordering the compilation of Japan’s first historical anthologies—the Kojiki and Nihonshoki—and establishing a system of rule whereby his closest relatives had full control over the court, ensuring that his bloodline remained on the throne for over 100 years.

In 680, the emperor built a temple to pray for the recovery of his wife, Uno no Sarara, who had fallen ill. Ironically, while she made a full recovery, he died before the temple could be completed. Nevertheless, his wife saw through the completion of the temple and named it Yakushiji after its main object of worship, Yakushi Nyorai—a Buddha renowned for his ability to cure illnesses.

When the capital moved to Heijō, Yakushiji moved with it to a location just a 20-minute walk from where I live. Although I could visit every day if I wanted, I’m embarrassed to say I’ve only been there twice. The temple grounds are fairly standard, but the three statues that make up the Yakushi triad are a sight worth seeing. A ticket that grants access to all areas of the temple complex can be purchased for ¥1000.

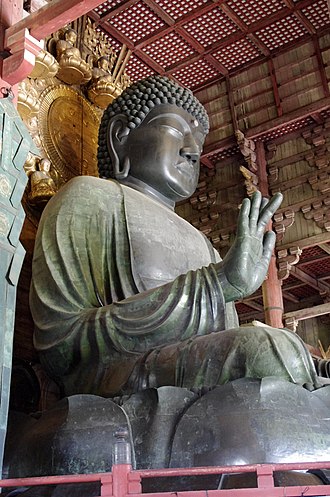

Tōdaiji

Established: 758

Sect: Kegon

Main object of worship: Vairocana Buddha

Original Area: 170 acres

Tōdaiji—the Great Eastern Temple. As you can see from its area, it dwarfs the others! Everything about it is big, from its massive temple complex to its huge main hall(the largest wooden building in Japan), and its 50 ft tall statue of the Vairocana Buddha. To have grown so huge, this temple had to have had a great story behind it, right? Let’s take a look at the history of Tōdaiji.

Emperor Shōmu and Kōmyō Kōgō

Emperor Tenmu’s grandson, Emperor Monmu, was in control of the country when preparations to move the capital to Heijō got underway. He died three years before the move could be completed, but as his son was still too young to take the throne at the time, his mother and sister took turns to rule the country in his stead. In 724, when he came of age, his sister stepped down and allowed him to ascend as Emperor Shōmu.

Emperor Shōmu married Kōmyō Kōgō, daughter of Fujiwara no Fuhito, who was the son of Fujiwara no Kamatari. As Emperor Shōmu’s mother was also Fuhito’s daughter, this made Kōmyō Kōgō the emperor’s aunt. The two famously had a good relationship, as suggested by the fact that their tombs are located within 160 ft of one another. Kōmyō Kōgō’s diligence and confidence perfectly complimented Emperor Shōmu’s quiet and reserved character. Together they made a number of contributions to the capital’s welfare system. However, one problem threatened to destroy everything they had achieved: the two struggled to produce an heir.

In the year 727, Kōmyō Kōgō succeeded in giving birth to a son, but he died just a year later. Bereaved, the couple built a small villa at the foot of Mount Wakakusa and stationed nine priests to pray for their late son’s soul. Over time, the area developed into a temple which became known as Konshuji.

Kōmyō Kōgō gave birth to her second son a year later, but he died at the age of 16 under suspicious circumstances. Eventually, the emperor gave up and named his daughter his successor(which led to a whole other set of problems, as you’ll see later).

The establishment of provincial temples

In 740, Emperor Shōmu went on an impromptu pilgrimage, moving the capital three times in the space of five years before finally returning it to Heijō. Two of his most valued statesmen/scholars had returned from Tang China in 735, bringing with them a smallpox epidemic and indirectly sparking a rebellion in the west of the country. The stress was too much for the mild-mannered emperor, who moved the capital first to the south of Kyōto, then to Ōsaka, then to Shiga before coming to his senses.

During his time away, he decided that the best solution to all the country’s problems was to build a state-sponsored temple in each province of the country. In the capital’s case, Konshuji was selected. In 742, it was developed into a larger, grander temple complex and renamed Konkō-myōji(Tōdaiji’s official name). Upon its completion, It would come to serve as the official state temple for the country, holding jurisdiction over all other provincial temples.

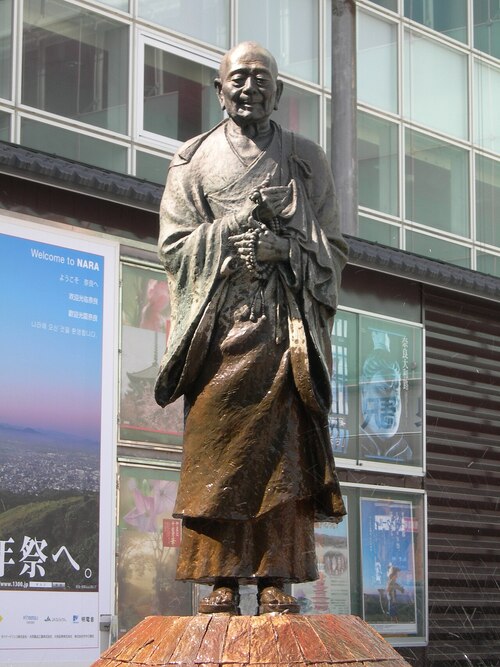

In addition to the establishment of provincial temples, Emperor Shōmu decided to build a giant Buddhist statue to watch over and protect the country. Construction began while he was still in Shiga, but he had the completed parts moved to Heijō, where he finished the project. It was a long and arduous ordeal that required the assistance of a great number of people and large donations from some of the wealthiest landowners around the country. The emperor had no choice but to ask his arch nemesis, Gyōki—the most charismatic monk in the country—for help.

Gyōki

Gyōki had gotten himself in trouble with the court several times for wandering out of his area of jurisdiction and preaching to poor farmers living on the outskirts of the capital. During the Nara era, priests were forbidden from working outside the confines of their parish. Gyōki frequently broke this rule to travel unauthorised around the country carrying out various kinds of community service, including building bridges across rivers and constructing service stations for travellers.

With the exception of priests, it was the duty of every person in the country to pay taxes, mostly in the form of crops, cloth or crafts. A number of people in each province were tasked with carrying these items to the capital on behalf of their towns. For some of the more distant provinces, this was a long and arduous journey, and it wasn’t uncommon for people to die of exhaustion or heat stroke along the way. Gyōki’s work made the trip a little easier and led to a significant reduction in the number of deaths. For that reason, he amassed a great amount of fame throughout the country despite being extremely unpopular with the court.

The Vairocana Buddha

Now, however, Emperor Shōmu needed to rely on Gyōki’s fame—despite the fact it had been obtained through illegal means. Gyōki agreed to help and set about preaching the benefits the Great Buddha could bring to the country. With the help of his followers, the statue was completed in 752. Sadly, the emperor didn’t live to see its completion. An Indian monk named Bodhisena who was living in Daianji at the time painted the eyes on the 50 ft tall statue, marking its official completion. Peace would finally be restored to the country once more(although a theory exists stating that far from bringing peace to the nation, the mercury used in the statue’s creation seeped into the capital’s water supply and poisoned it to the point where the surrounding area was no longer inhabitable, forcing the court to have to move the capital to a new location in proximity to three major rivers).

The main hall, in which the Great Buddha is housed, was completed in 758. A monk by the name of Rōben was appointed the temple’s first chief administrator. Emperor Shōmu, Gyōki, Bodhisena and Rōben became known as the four sages of Tōdaiji.

The Burning of Tōdaiji

All went well until the fire that burned down Kōfukuji in 1181 burned down most of Tōdaiji too. Only a couple of gates and a handful of small buildings remained. Reconstruction began immediately and was completed in 1195.

The temple burned down a second time in 1567, this time due to a battle that broke out between the Miyoshi clan and Matsunaga Hisahide—the two great samurai powers in the area at the time. Makeshift repairs were made to the head of the Great Buddha, and a small temporary hall was constructed, but in 1610, that too was destroyed by a typhoon. The Great Buddha remained outside until a monk named Kōkei decided to gather support from the people and the shōgunate and reconstruct the hall. It was completed in 1709 and stands today, 190 ft long, 167 ft wide and 160 ft tall. The reconstructed hall’s height is 40 ft taller than that of the original, but its length is a third shorter.

Now, the temple comprises the eastern area of Nara Park, and—aside from the 1,000-plus deer that roam the park—serves as Nara’s chief tourist attraction. The main hall and museum each cost ¥800 to enter, but a special ticket that grants entry to both can be purchased for ¥1,200. Several other of the complex’s buildings can also be entered for a fee. If you decide to visit Tōdaiji, at the very least I recommend visiting the main hall and enjoying the Great Buddha with a greater understanding of its history.

Saidaiji

Established: 765

Sect: Shingon Ritsu

Main object of worship: Shaka Nyorai

Original Area: 118 acres

Emperor Shōmu was succeeded by his daughter, who ascended the throne as Empress Kōken. However, as I mentioned before, this caused various problems for the court. As tradition dictated that the Imperial Line continued through a male descendant of the first emperor, Shōmu’s daughter was only ever intended to be a placeholder until the next emperor could be decided. As such, she was forbidden from bearing children—producing a son could have potentially led to a succession dispute. For this reason, Empress Kōken led a lonely life, caring for her sick mother, who passed away in 760.

Her only source of comfort was a monk named Dōkyō, who prayed for and helped care for her mother in her final days. Kōken grew very close to Dōkyō. By that time she had already passed the throne to a distant cousin—a grandson of Emperor Tenmu, who ascended as Emperor Junnin— but continued to run the court from behind the scenes with Dōkyō as her primary advisor. This displeased the new emperor’s right-hand man, Fujiwara no Nakamaro, who started a rebellion in 764 in a bid to expel Dōkyō from the court and return power to his puppet. The rebellion failed, Nakamaro was killed, and poor Emperor Junnin(who played a very minimal role throughout the entire affair) ended up being exiled to Awaji island, where he died the following year(under suspicious circumstances).

Kōken reascended, this time under the new name of Empress Shōtoku. Distraught by all that had happened, she built a temple in the capital’s west to pray for the souls of those whose lives had been lost in the rebellion. She named this temple Saidaiji(西大寺), the Great Western Temple, in contrast to Tōdaiji, the Great Eastern Temple, on the far eastern side of the capital.

Saidaiji fell into decline in the Heian era. Many of its buildings and towers were lost to fires and typhoons throughout the years, and the impoverished temple ended up under the jurisdiction of Kōfukuji. Efforts were made to restore its buildings several times in the following centuries until, finally, a reconstruction carried out in the Edo era shaped Saidaiji into the form we see today. It’s a small temple but a nice one—just a 15-minute walk from where I live. (If you’ve read through this entire article, you probably now have enough information to pinpoint my location. No stalkers, please!) Entry to the temple’s three main buildings costs ¥800.

Summary

Admittedly, the main focus of this article ended up being the history of the Asuka and Nara eras, but hopefully I’ve given you an insight into some of Nara’s most famous temples and helped add a new layer of enjoyment for you should you ever decide to visit. Of course, these seven aren’t necessarily the largest or most impressive temples in Nara, but they were the most influential for a considerable period of time. Tōshōdaiji, another Nara-era temple close to Yakushiji, is also worth a visit. If I’m being honest, though, the temples in the south of Nara are more likely to leave a lasting impression. Asuka-dera, Tsubosaka-dera, Hasadera, Taima-dera, Oka-dera, Abe-Monjuin… Each has its own unique characteristics that make it worth visiting. If you want any more specific information, leave a comment and I’ll see if I can help you.