Yamamoto Kansuke – Was he real?

Japanese history is littered with characters whose resumes are flooded with Herculean tasks so impressive and numerous that they force you to raise an eyebrow and ask the question ‘Were they real?’. In the case of Yamamoto Kansuke, tempting as it is to believe his accolades, the evidence supporting them is underwhelming to say the least.

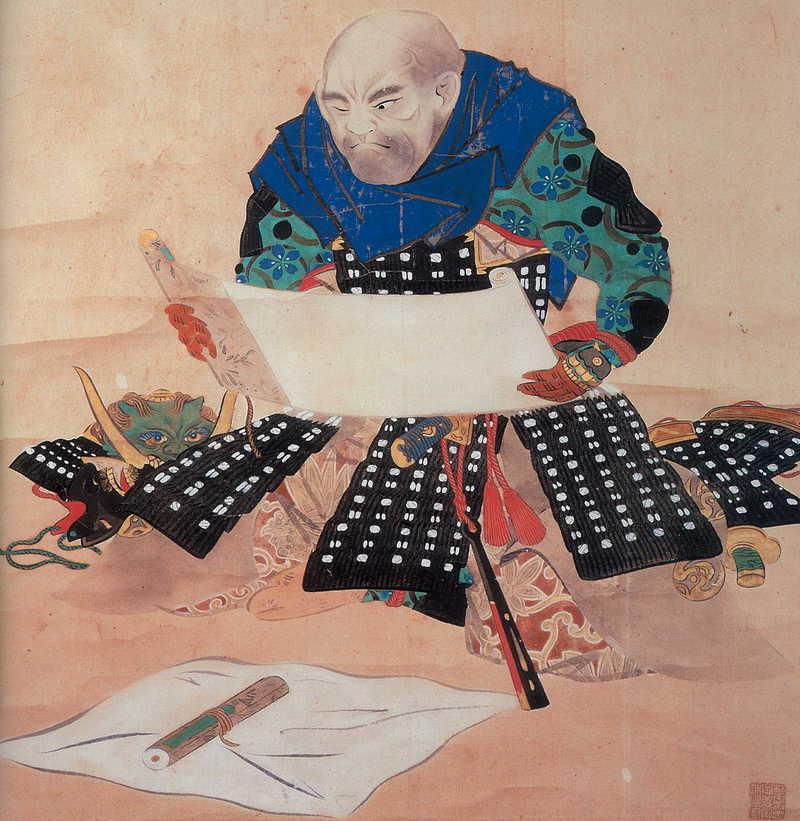

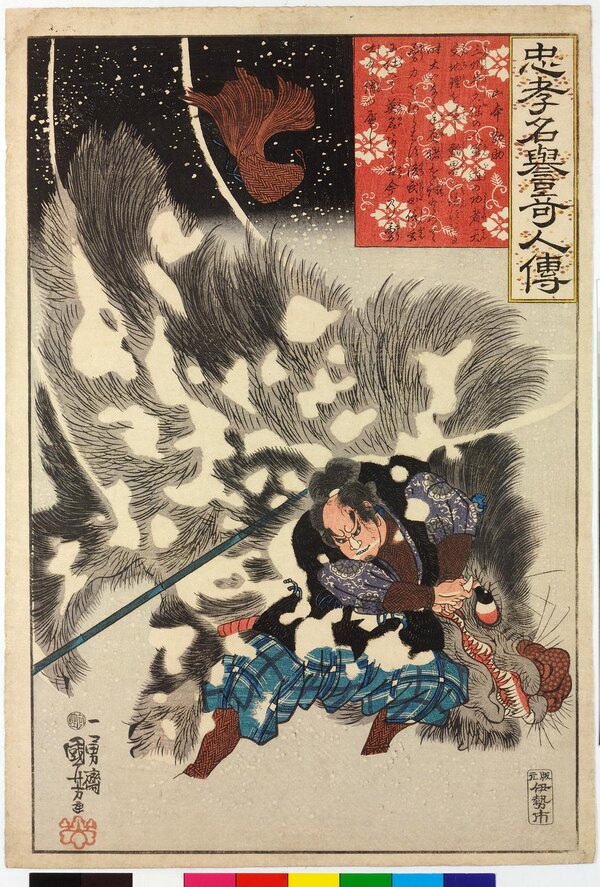

Arguably the second most famous general in all of Sengoku(losing out only to Kuroda Kanbei), Yamamoto Kansuke stood by Takeda Shingen, one of the top daimyō in the country, who, over the course of his career, managed to grow his empire to a whopping four times the size of that which he took from his father. How is it possible that while Shingen’s achievements can and have all been verified, those of his most trusted general—a man whose life inspired a number of Jōruri plays and ukiyo-e paintings in the Edo era as well as books and drama series in recent history(even a Taiga drama!)—cannot? Let’s dive into the life of this larger-than-life figure and determine once and for all whether or not he was real.

Yamamoto Kansuke as recorded by history

The Kōyō Gunkan

Over 99% of what we know about Yamamoto Kansuke comes from the Kōyō Gunkan, a war chronicle documenting events surrounding the Takeda clan up until the point of its demise. These events were written in real time, giving the text an air of credibility that led to it being adopted as a military guide in the early 17th century. However, in the late 19th century, Sengoku era texts came under the scrutiny of modern research methodology. Many—the Kōyō Gunkan included—were deemed to be riddled with inaccuracies, exaggerations and blatant fiction. In Kansuke’s case, for example, the text first states that he was born in the year 1500. However, a later section implies he was born in 1493. If the Kōyō Gunkan can’t even maintain consistency within the confines of its own pages, can anything it teaches us be trusted?

The Bukō Zakki

Cross-referencing the Kōyō Gunkan with other texts only deepens the mystery. The Bukō Zakki, a text completed in 1696, makes several mentions of Kansuke. Despite the fact it was written more than a hundred years after his death, historians believe the majority of the information contained within its pages to be accurate. What’s worth noting is the fact that at one point in this text, a priest claiming to be Kansuke’s son states that the Kōyō Gunkan was almost entirely fictitious, and that his father(while he did exist) was merely a low-ranking retainer of the Takeda clan. Research conducted in the late 19th century backs this claim up, concluding that Kansuke was most likely a foot soldier of Yamagata Masakage, one of Takeda Shingen’s four greatest generals.

However, not everything in the Bukō Zakki can be taken at face value: one section details the story of sword master Kamiizumi Nobutsuna travelling to Suruga to meet the Makino clan, under whose jurisdiction Yamamoto Kansuke was living at the time. Nobutsuna supposedly had one of his disciples face Kansuke. After a lengthy showcase of skills, Kansuke emerged victorious. However, a number of local samurai who were jealous of Kansuke’s talent disputed the result and began to spread rumours that he had lost the duel. Dismayed, Kansuke embarked on a journey to improve his skills further and find a place he would be welcome. While this story would make a great opening scene for a rags-to-riches movie about a talented underdog samurai, several other sources state that Nobutsuna didn’t enter Suruga until after Kansuke’s death, strongly suggesting that the story was fabricated.

Fading existence

If neither the Kōyō Gunkan nor the Bukō Zakki can be trusted, how are we supposed to know what we can and can’t believe about Kansuke? Very few other sources from the time he was alive give us anything else to go on. If Yamamoto Kansuke was as renowned and accomplished a general as the Takeda would have us believe, is it really possible that he could make it to the Edo era without being mentioned in any other major samurai clans’ records? This lack of evidence has caused Kansuke’s character to fade over time. Whereas first, he was revered as a legendary general in the Edo era, later, in the Meiji era, he was branded a foot soldier. Eventually, in 1959, a book was written disputing his existence entirely.

In the last fifty years, however, the tide has been changing due to the emergence of new evidence to support the theory that Kansuke did in fact exist. Before we study this evidence, though, let’s first take a look at Kansuke’s life as detailed in the Kōyō Gunkan and other texts.

The Life of Yamamoto Kansuke

Early Life

Yamamoto Kansuke was born as Yamamoto Gensuke in either 1493 or 1500, in either Mikawa province or Suruga province. He was dark-skinned, short, had only one eye and walked with a limp(the Kōyō Gunkan gives no reason as to why). The Kaikokushi—a chronicle of the history of Kai province, completed in 1814—states that at the age of 12, Kansuke was adopted by Ōbayashi Kanzaemon, a retainer of the Makino clan, who ruled Ushikubo Castle. The ‘Kan’(勘) character of Kansuke’s name was most likely awarded to him by his adoptive father.

At the age of 20(or 27), he embarked on what would become a ten-year journey of self-improvement. He first travelled to Mount Kōya, home to the chief temple of the Shingon sect of Buddhism, and studied military tactics under the mountain priests. After leaving Mount Kōya, he continued his journey across the west of Japan, serving briefly under a number of famous daimyō and honing his skills further. In addition to acquiring a repertoire of military techniques, Kansuke’s journey allowed him to observe and study a number of different castle constructions. Adopting the construction methods he believed to be beneficial allowed him to later become a master castle designer.

Imagawa Yoshimoto

Kansuke returned to the Ōbayashi clan at the age of 35 only to discover that his adoptive father had produced an heir and, therefore, didn’t have a need for Kansuke anymore. And so Kansuke changed his family name back to Yamamoto and continued his travels east. Eager to finally start his career, he decided to seek out a military position under a daimyō. Imagawa Yoshimoto, the ruler of Suruga, agreed to meet with Kansuke, but upon seeing his limp, his one eye, the many scars he had picked up during his travels and the fact that he had arrived without a single servant in tow, Yoshimoto instantly dismissed him. Dismayed, Kansuke remained in Suruga, where he stayed with the Ihara family for the following nine years.

Takeda Shingen

In 1543, Takeda Harunobu(who would later take the Buddhist name of Shingen) was looking for an architect. He had just usurped his father’s land, army and estate, and was looking to expand his new empire. Itagaki Nobukata, one of his most loyal advisors, had heard rumours of a one-eyed man with a limp who, despite having no long-term work experience to speak of, was apparently skilled in the art of castle design.

Shingen decided to meet with this mysterious figure if for no reason other than the fact that he was intrigued by the idea of a man who at a glance appeared unhirable spreading his name across such a vast number of provinces. He arranged a horse, a spear and a servant for Kansuke so that he wouldn’t be looked down on when he entered Kai. Initially, he had planned to hire Kansuke for an annual salary of 100 kan(a whopping ¥12,000,000 in modern money), but upon meeting him, he instantly recognised his talent and doubled the amount!

Shingen relied on Kansuke for advice on taking down castles and information about various regions of the country. This information was indispensable to Shingen, who was planning to invade the neighbouring province of Shinano, and it earned Kansuke a place by his side as one of his most trusted advisors. So strong was Shingen’s trust in his new advisor that when a retainer by the name of Nanbu Munehide became jealous of the treatment Kansuke was receiving and began to criticise him, Shingen confiscated part of Munehide’s territory and raised Kansuke’s salary to 300 kan!!

Suwa Yorishige’s Daughter

Working for the Takeda clan, Kansuke honed his skills of intelligence gathering, strategy formation and castle design and construction. In 1544, shortly after beginning his invasion of Shinano, Shingen defeated a local daimyō by the name of Suwa Yorishige. Taken in by Yorishige’s daughter’s beauty, he decided he wanted her for his concubine.

While the majority of his generals advised him against this, stating that she’d slit his throat while he was asleep, Kansuke reasoned that if she were to bear Shingen’s son, that son could be installed as the new ruler of Suwa, making it easier to gain the trust of the local people. Shingen decided to take Kansuke’s advice. Two years later, Yorishige’s daughter gave birth to a baby boy, who, upon coming of age, would be named Katsuyori and would eventually go on to rule the Takeda empire. Kansuke even helped to construct a new castle, Takatō Castle, in Suwa, so that Katsuyori could rule smoothly over his new territory.

General Kansuke

Despite his acclaim as a legendary general of the Sengoku era, the Kōyō Gunkan makes only two mentions of Yamamoto Kansuke’s military accomplishments. The first surrounds Shingen’s rivalry with a daimyō named Murakami Yoshikiyo, who controlled the north of Shinano. Their first encounter was a battle that took place in 1546. Yoshikiyo forced Shingen to suffer his first defeat, an event so traumatising, he remained on the battlefield for twenty days until he was mentally stable enough to return home.

After regaining his composure, Shingen decided to take a second stab at Yoshikiyo by attacking Toishi Castle. Yoshikiyo soon arrived on the scene, and the battle commenced. Once more, Shingen quickly found himself on the losing side. When all seemed lost, Kansuke asked permission to borrow 50 men, leading them away from the battlefield in a formation that suggested they were the Takeda army’s main troop. This decoy gave Shingen time to regroup and restrategise, allowing him to stay in the battle a little longer. In the end, the Takeda lost. However, had it not been for Kansuke’s decoy tactic, the result could have been a lot more devastating. Shingen was so pleased, he promoted Kansuke to infantry commander and granted him a stipend of 800 kan(equivalent to 96,000,000 yen—more than double the annual salary of the prime minister of Japan as of 2025!!!)

Uesugi Kenshin

Eventually, Shingen succeeded in defeating Yoshikiyo and forced him to flee to Echigo, where he found an ally in Uesugi Kenshin. Renowned for his sense of justice, Kenshin rarely refused to help someone in need. And so when Yoshikiyo came running to Echigo, begging for him to take down the Takeda, he couldn’t say no. Shingen was a far greater opponent than any he had ever faced up until that point, however. In all likelihood, Kenshin’s real reason for accepting the challenge was the fact he had already realised that if the Takeda succeeded in taking over Shinano, Echigo would be next.

The two entered into a rivalry that saw them squaring off five times in an area of land in the very north of Shinano known as Kawanakajima. The majority of these battles were relatively short and tame, each man simply wishing to assert his dominance and warn the other off proceeding further. The fourth, however, went down in history as one of the most epic battles of the Sengoku era. This is where we find the Kōyō Gunkan’s second report of Yamamoto Kansuke’s military prowess.

The Battle of Kawanakajima

Shingen and Kenshin’s legendary fourth encounter began with Kenshin marching 13,000 men to Kawanakajima and taking up camp at the summit of Mount Saijo. Shingen led an army of 20,000 and took up camp at the base of the mountain, near Kaizu Castle—which Kansuke had constructed several years earlier after realising the Kenshin problem wasn’t going away.

The two armies stared each other down for several days until Kansuke came up with a plan to break the stalemate. He suggested splitting the Takeda army into two divisions and leading 12,000 men up the back of the mountain to launch a surprise attack on Kenshin’s army, forcing his men to retreat to the bottom of the mountain, where the rest of the Takeda army would be lying in wait. He called it the ‘Woodpecker strategy’, in reference to the tactic a woodpecker employs when it attacks the back of a tree to force the bugs hiding inside to leave.

A dense fog engulfed the area that night, concealing the Takeda army and creating the ideal cover for their movements. Baba Nobuharu led 12,000 men silently up the back of the mountain. However, as Kenshin looked down on Kaizu castle, he noticed a suspiciously large amount of steam rising from within the castle walls. This could only mean that a greater amount of rice was being cooked than normal, which suggested the Takeda were planning something big. Acting on this hunch, he marched his men down the mountain and concealed them in the fog. When the sun rose and the fog cleared, the Takeda army found itself surrounded by 13,000 enemy soldiers while the bulk of its men were left standing confused at the top of the mountain.

Yamamoto Kansuke’s death

The battle commenced. Heavily outnumbered and with less than half his army at hand, Shingen was at a major disadvantage. He did his best to fend off the Uesugi troops until Nobuharu led his men down the mountain, at which point the two sides were able to fight more evenly. Kansuke, feeling responsible for the situation, drew his sword and charged head-first into the battlefield, where he was instantly surrounded by a number of enemy soldiers and stabbed to death with spears. The battle eventually ended in a draw. Both commanders led their armies back to their respective territories. Shingen may not have lost the battle, but he did lose several thousands of men, including his younger brother and, of course, his most trusted general.

Was he Real?

So now that you have some degree of understanding about Yamamoto Kansuke’s life, let’s return to the debate. Was he real? Well, for hundreds of years, the evidence available suggested that he wasn’t. However, as I mentioned earlier, evidence discovered in recent years supports the theory that he was.

Shingen’s lost letters

In 1969, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation ran a Taiga drama called ‘Heaven and Earth’, focussing on the lives of Shingen and Kenshin. In one particular scene, Shingen writes a letter to a retainer and signs his name using his kaō. Upon watching this scene, a certain viewer recognised Shingen’s kaō and went to dig out a chest containing old letters which had been with his family for generations. He brought the letters to a library, whose staff arranged for an expert to examine them. Lo and behold, they were authentic. And among the many details contained within them was the name ‘Yamamoto Kansuke’.

Finally, after hundreds of years, the world had definitive proof of Kansuke’s existence… Or did it? Despite the letters’ authenticity, the debate among researchers raged on. Although Yamamoto Kansuke’s name had been confirmed, the Chinese character representing his name was different from the one used in the Kōyō Gunkan. Kansuke’s name is represented in the Kōyō Gunkan by the characters ‘勘助’, whereas the name in the letter read ‘菅助’. While both names have identical pronunciations, it doesn’t change the fact that they technically aren’t the same name.

The debate

Some researchers claimed that minor as this discrepancy was, it was enough to refute the theory supporting Yamamoto Kansuke’s existence. Others, however, pointed out that there were numerous examples of samurai changing the Chinese characters that made up their names multiple times throughout the course of their lives. They argued that in samurai society, as long as the reading of the character matched, it wasn’t important which character someone used. If the person referred to in the letter is indeed Yamamoto Kansuke, however, the letter’s content suggests that he wasn’t a mere foot soldier but rather a high-ranking officer who was close to Shingen. This corroborates the image of Kansuke depicted in the Kōyō Gunkan.

The story doesn’t end there, though. In 2007, Kansuke received his own Taiga drama, ‘Furinkazan’. One year later, two new Shingen letters were found, addressed to the same Yamamoto Kansuke from the 1969 letter. These letters contained Kansuke’s Buddhist name, giving them a further level of credibility.

One letter was dated 1548. It thanked Kansuke for his work in Ina, an area in the south of Shinano, and detailed the reward he received. The other was undated. Its contents included a request for Kansuke to think up a new battle strategy and to check up on one of Shingen’s retainers who was sick at the time. The tone of the letters suggested that Kansuke was a messenger rather than a general. It’s worth noting, though, that a messenger was an important position in the Sengoku era that could not be obtained without first receiving a high level of trust from a daimyō. Letters were kept short and void of certain details lest they be intercepted by the enemy. The main job of a messenger was to convey the most important details verbally to the recipient.

Conclusion

The Kōyō Gunkan tells a tale of an underprivileged, low-ranking samurai, who, despite his many obstacles, through hard work and dedication became a general to one of the most renowned figures of the Sengoku era. Was he real though? While the evidence we have now strongly suggests that he was, conflicting stories and nuances beg a new question: ‘Was he the multi-talented tactician history made him out to be?’ People in the Edo era were certainly willing to believe he was. People in the Meiji era were more sceptical. It might take another Taiga drama to find a final, definitive answer.