Japanese history overview Pt. 9: The Edo era Pt. 2

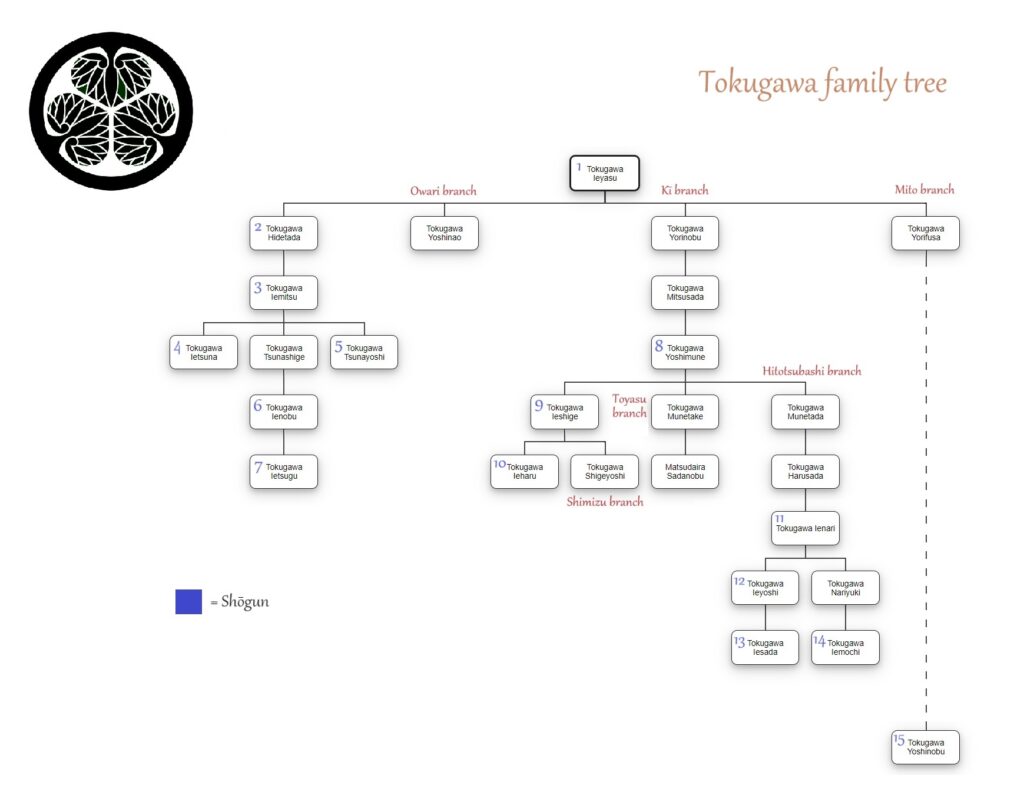

Welcome to part two of this overview of the Edo era. Whereas in part one we focussed on central administration and foreign policy, this time we’re going to be paying attention to labour issues, taxes and the economy. The second half of the Edo era was characterised by three major reforms, the need for which was brought about by depleting gold and silver supplies, an ever-increasing population, and climate changes. While this might not sound as exciting as the constant stream of battles offered by the previous 500 years of Japanese history, the innovative solutions to these problems devised by the shōgunate would go a long way towards integrating Japan into the modern world. It’s also interesting to take a look at the trial and error process that went on in a country trying to reinvent itself with limited help from the outside world. With the Kyōho reform already having been covered in part one, let’s take a look at what happened after its orchestrator, Tokugawa Yoshimune, stepped down from his post.

Tokugawa Ieharu

In 1745, Yoshimune handed the title of shōgun to his oldest son, Ieshige, and spent the following six years controlling the shōgunate from behind the scenes before he died. With the country running smoothly, there was very little for Ieshige to do. He ran the shōgunate until 1760, at which point he passed the title of shōgun to his first son, Ieharu, who also had very little to do. Surrounded by a crack team of experts set up by his father and grandfather, he was free to immerse himself in his hobby of shōgi, in which he worked his way up to the impressive level of 7th dan.

Tanuma Okitsugu

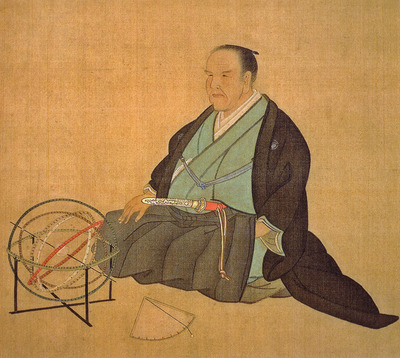

Among Ieharu’s crack team was a man by the name of Tanuma Okitsugu, whose father had been hand-picked from Yoshimune’s servants in Kī to follow Yoshimune to Edo and serve the shōgunate. When his father died in 1735, Okitsugu inherited his 600 koku of land and was selected to be pageboy to Ieshige. Earning Ieshige’s trust, he rose through the ranks of the shōgunate until he was finally promoted to rōjū and awarded a whopping 57,000 koku of land. Okitsugu is the only example in the Edo era of someone ascending from pageboy all the way up to rōjū, which should give you some idea as to his genius and expertise.

Silver

While Okitsugu didn’t conduct a reform, he did attempt to make a number of changes to the country, mainly centering around money. For example, since the amount of cultivatable land was dwindling, he decided to tax merchants, opening up a new line of tax revenue for the shōgunate. He also tackled the problem of the lack of a consistent conversion system for gold and silver. Due to the fact that the country’s major gold mines were mainly situated in the east and the silver mines in the west, most of the trading that occurred in the east(chiefly Edo) was conducted using gold, while most of the trading that occurred in the west(chiefly Ōsaka) was conducted using silver. The problem was that whereas various denominations of gold coins had been produced, silver was still traded by weight. Okitsugu created a new silver coin that could be used against all denominations of gold, eliminating the need to weigh the silver in order to figure out the necessary amount every time a transaction took place.

Volcanoes

Furthermore, Okitsugu conducted research into establishing new gold and silver mines, looked into cultivating areas of Ezo, and considered trading with Russia. Unfortunately, none of these plans panned out. Even more unfortunate was the fact that all his good work was undone by a series of natural disasters. It all started when two large volcanoes in Iceland erupted, spreading volcanic gases as far as Japan. (Incidentally, these eruptions are also assumed to be a factor in the chain of events that led to the French Revolution.) The problem was further exacerbated when two volcanoes within Japan itself erupted the following year. Between the gases brought over from Iceland and the dust from the Japanese volcanoes blocking out sunlight, the northern half of the country experienced a famine that lasted six years and is estimated to have killed over 900,000 people.

Besides being forced to take a break from his plans to handle this crisis, Okitsugu was also troubled by the fact that a large proportion of samurai were followers of Confucianism, which taught that when a series of natural disasters occurred, it was a sign that the country’s leaders were corrupt. Okitsugu’s popularity took a swift and severe beating to the point where someone killed his son in an effort to get him to step down. Okitsugu stood firm through the entire ordeal. However, when Ieharu died, he lost his backing. He was forced into retirement and had the majority of his land confiscated. Tanuma Okitsugu… Perhaps Japan’s most notable rags to riches to rags story.

Matsudaira Sadanobu

Of course, defaming Okitsugu didn’t solve the problems the country was facing. The shōgunate needed a new shōgun and a new leader. As Ieharu didn’t have any surviving sons at the time of his death, the title of shōgun went to Tokugawa Ienari, a great-grandson of Yoshimune from the Hitotsubashi branch of the Tokugawa clan. Matsudaira Sadanobu, a grandson of Yoshimune from the Toyasu branch, was chosen to replace Okitsugu. While the famine in the north had caused mass suffering across the majority of hans in the affected region, through a series of sound economic dealings, Sadanobu―who had been in charge of Shirakawa han at the time―had managed to weather the storm with a 100% survival rate among the residents of his domain! This impressive feat alone allowed him to rise to the top of the rōjū.

The Kansei Reform

Farmers

And so in 1787, with the vacant spots in the shōgunate filled, it was time for another reform: the Kansei reform. One glaring problem facing the country was the lack of farmers; between the death toll of the famine―which had finally come to an end―and Okitsugu’s economic plans having lured a great number of people to Edo, the countryside was lacking the farmers it needed to grow the rice that the economy depended on. In fact, the number of farmers is said to have decreased by 1,400,000 compared to ten years prior! Many of the farmers who had moved to Edo had not achieved the level of success they had expected. However, they also lacked the necessary funds to return home. Sadanobu offered to pay for their expenses and send them back to the countryside so they could start boosting the country’s rice yield again.

Finance

In preparation for future famines, Sadanobu ordered every daimyō to put aside 0.5% of their annual rice yield in a public storage facility. Like his grandfather, he also ordered frugality. In order to aid struggling daimyō and give them a new start, he ordered the cancellation of all loans whose repayments had been continuing for over six years(due to the interest rates of the time, after six years, the initial loan amount had already been repaid in full, and the borrower was now simply paying off the interest). Any loans taken out within the previous six years could be written off once the initial loan amount was paid off.

Rehabilitation

Sadanobu also created a rehabilitation facility for the homeless and criminals who had committed minor transgressions―a kind of prison/job training centre that provided full instruction on how to master jobs such as carpentry and road construction so that those undergoing the training would easily be able to find employment once leaving.

Title dispute

For all his efforts, though, Sadanobu’s career ended in a similar manner to that of Okitsugu’s. He had done everything right; the Kansei reform was, on the whole, a success. Just one small mistake led to his undoing. Perhaps ‘mistake’ is too strong of a word, though, since he didn’t have much control over the matter.

When Emperor Go-Momozono died without naming an heir, a distant cousin was chosen to be his successor. This cousin ascended the throne as Emperor Kōkaku. In 1788, Emperor Kōkaku began to feel a little awkward about the fact that while he was emperor, his father was still a mere prince. And so he asked the shōgunate for permission to award his father the title of dajō-tennō. Back in the early 17th century, however, in order to keep the court in check, Tokugawa Ieyasu made a set of extremely specific instructions regarding what the court could and couldn’t do. Awarding the title of dajō-tennō to someone who had not previously held the title of tennō(emperor) fell into the latter category. These rules had been followed for almost 200 years. Who was Sadanobu to suddenly decide to break them? Plus, there was no benefit whatsoever to the shōgunate in fulfilling Emperor Kōkaku’s request. Sadanobu swiftly rejected the proposal.

This would have been the end of the ordeal had it not been for the fact that the shōgun, Ienari, was in a similar situation to the emperor in that his father had not held the title of shōgun. He went to Sadanobu and asked permission for his father to be granted the title of ōgosho. Normally, this request would have been somewhat easier to fulfil than that of the emperor. However, having already refused the emperor’s request, approving the shōgun’s request would have sent a clear message to the people that the shōgunate considered itself to be of higher status than the court. While this may have been true in terms of power and wealth, it was vitally important for the shōgunate that, at least officially, it appeared to be working under the court. (The emperor still commanded a great deal of respect from the people, and, to most, the idea of him bowing to a higher power was unthinkable.) For this reason, Sadanobu reluctantly rejected the shōgun’s request. Naturally, this resulted in his dismissal from the shōgunate.

The Foreign Threat

Russia

Meanwhile, in 1793, a Russian navigator by the name of Adam Laxman made his way to Japan to return a number of castaways that had been swept up on Russia’s shores during a storm. In return, he asked the shōgunate for permission to trade with Japan. After a short negotiation, he received permission to trade at Nagasaki port under the same conditions that were made available to the Dutch. While Laxman didn’t venture to Nagasaki himself, he returned home with the good news that the trade route had been opened. However, when a second Russian, Nikolai Rezanov, ventured to Japan just ten years later, things didn’t go as smoothly. In this short space of time, the shōgunate had been taken over by a new set of officials who didn’t recognise Rezanov’s claim to have permission to trade in Nagasaki. After being turned away from the port, he returned to Russia in search of new opportunities. He still had a little pent-up resentment over the way he had been treated, though. And so, in 1806, he sent a small fleet of his men to attack Sakhalin―the area to the north of Hokkaido(a kind of no man’s land between Japan and Russia). Rezanov’s men continued to attack the area for close to two years before the Russian emperor realised what was going on and called off the unsanctioned assaults. The whole affair left Japan somewhat wary of foreigners.

Britain

Tensions increased further in 1808 when a British ship sailed into Nagasaki sporting the Dutch flag. The moment the ship was granted entry to the port, the crew lowered the flag and raised the British flag in its place. When two Dutch officials boarded the ship to assess the situation, they were taken hostage. The captain refused to return the men until Nagasaki supplied them with water, food and fuel. As the port didn’t have the manpower to deal with the situation, they gave in to the captain’s demands. The hostages were released, and the ship left the port. Matsudaira Yasuhide, the man in charge of the port, took responsibility for the incident and killed himself. This event destroyed the little amount of trust Japan had left in foreigners.

In 1811, a third Russian, Vasily Golovin, travelled close to Japan to measure the area of a group of islands situated between Russia and Japan. Upon docking at the nearest port to request water and supplies, however, he was arrested. Had it not been for the unrelenting efforts of his first mate and a kind local Japanese translator, Golovin may have spent the rest of his years a prisoner rather than being allowed to return to his country in 1813.

The decline of the shōgunate

Eventually, in 1825, the shōgunate decided to make its feelings toward the foreign threat official by decreeing that any non-Japanese ship entering Japanese territory could be fired at indiscriminately and without consequence. In 1837, this law was utilised to attack the Morrison, an American trade vessel heading towards Japan to return a number of drifters it had found on nearby islands. Naturally, the captain was shocked when his ship began to be bombarded with cannonballs despite the fact he was simply trying to conduct an act of kindness. Even the general populace felt that the law needed a little tweaking. Support for the shōgunate was beginning to wane.

The situation escalated further in 1833 when another famine broke out. This one also lasted six years and killed 1.25 million people. Many farmers flocked to Edo in search of work. Most failed to find any. This led to a significant increase in crime. To make matters worse, rather than distribute rice to the starving people from the storage facilities Sadanobu had set up in the late 18th century, local officials all over the country began sending rice to Edo in celebration of the inauguration of the new shōgun, Tokugawa Ieyoshi. Rather than carry out their assigned duty of protecting the people under their jurisdiction, these officials opted to butter up their new boss, resulting in the deaths of tens of thousands.

Ōshio Heihachirō’s rebellion

In 1837, a low-ranking official in Ōsaka by the name of Ōshio Heihachirō decided to do something about this corruption. He gathered a small army of 300 men and marched them through the streets, setting fire to shōgunate buildings as they made their way towards Ōsaka Castle. While the rebellion was inevitably put down and Ōshio was forced to kill himself, he did manage to destroy one-fifth of the city―an impressive feat for such a small band of mercenaries. In addition, his actions inspired a similar rebellion further north a few months later. Most importantly, though, the rebellion let the people know that they had allies within the shōgunate itself, who were just as unhappy with regard to the way the country was being run. Many historians believe that minor as this rebellion was, it marked the beginning of the shōgunate’s downfall.

The Tenpō Reform

With the country in disarray, the time was ripe for yet another reform: the Tenpō reform. The Edo era’s third and final reform would be conducted by Mizuno Tadakuni, right-hand man to the newly appointed shōgun. As it was no secret that there had been a fair amount of bad blood between Ieyoshi and his father, Ienari, Tadakuni, who had achieved his position via a series of well-conducted bribes, rid the shōgunate of anyone loyal to the former shōgun and replaced them with a new team hand-picked by himself and Ieyoshi. This new team was faced with two Herculean tasks: helping the country recover from the latest famine and establishing a new foreign policy.

Radical measures

Unfortunately for the shōgunate, Tadakuni had little experience in solving any problem other than that of convincing those above him to accept his bribes. The amount of thought poured into his reform was, therefore, considerably less than that of Sadanobu. For example, whereas Sadanobu provided farmers the means to return from Edo to their domains, Tadakuni not only banned farmers from moving to Edo, but also forced all farmers currently living in Edo to return to their hometowns without offering any kind of compensation or support.

Elsewhere, he ordered artisans and merchants to reduce their prices in a bid to force deflation. However, this only resulted in artisans reducing the quality of their wares in order to compensate for lost earnings. In addition, whereas Tokugawa Yoshimune and Matsudaira Sadanobu both made efforts to encourage frugality and discourage spending money on entertainment or other such frivolous pursuits, Tadakuni took it a step further by reducing the number of kabuki theatres from 211 to a mere 15 and banning all performances he deemed non-educational.

Foreign policy

With regard to the foreign threat, in 1842, after Qing was defeated by Britain in the first Opium War, Tadakuni had little choice but to take a more lenient approach towards foreign merchants’ requests to trade with Japan. Throughout history, Japan had remained consistently in awe of China, and the numerous rulers that commanded the island country through the various ages had always tried to stay on the good side of whatever dynasty controlled the vast mainland. Even in the 19th century, the notion that China could be defeated by a foreign force was inconceivable. Britain’s victory shook Japan to its core and forced it to re-evaluate its decision to close the country off to all but a handful of nations. Mere months after Qing’s defeat, Tadakuni issued an edict decreeing that any foreign vessels requesting assistance were to be supplied with water, fuel and any other necessary supplies.

Needless to say, a lot of Tadakuni’s decisions were unpopular with both the daimyō and the farmers. Faced with the threat of the country’s gates opening to foreign forces and having lost most forms of the entertainment to which they would usually turn to take the edge off this kind of tension, Tadakuni’s popularity among the general populace was teetering. In 1843, he put the final nail in his coffin by relocating a number of daimyō who controlled areas of land situated on the outskirts of Edo and Ōsaka. His plan was to concentrate the shōgunate’s territories in order to better prepare the country to face a potential foreign invasion. However, he not only angered the daimyō in charge of these areas but also the people living under their jurisdiction, who were worried that they might lose the benefits that had been granted to them by their former rulers. Upon making it clear to the daimyō that the shōgunate could take their land and relocate them on a whim, Tadakuni lost the last of his dwindling support. The Tenpō reform was over.

Prelude to Bakumatsu

After Tadakuni was removed from his position, foreign pressure began to increase. The shōgunate did its best to turn away Russian and American ships requesting permission to dock in ports close to Edo and trade with Japan. Finally, in 1853, an American naval officer named Matthew Perry led four ships to the east of the country and demanded that Japan form a trade agreement with the U.S. He gave the shōgunate a year to consider the situation before returning with ten larger, more threatening ships. Abe Masahiro, the head of the rōjū, gathered the country’s greatest minds and begged for their advice, but, alas, not one of them was able to come up with a solution that didn’t involve Japan opening its gates to foreign vessels. Masahiro had no choice but to give Perry what he wanted.

The decision led to a ten-year period in Japanese history known as Bakumatsu―the end of the shōgunate. Short as this period was, the action and drama it contains come close to rivalling Sengoku. Unfortunately, however, its details require a whole other article. Sufficient to say, with the country divided, a number of the more prosperous and powerful hans(chiefly Satsuma and Chōshū) amassed an army large enough to take down the shōgunate. And from the wreckage of the lost age of samurai, they formed a new, modern government―one that was ready to embrace the outside world and develop itself in accordance with terms laid out by a global community rather than those of a closed-off shōgunate. In 1868, the Meiji Restoration began. Control of Japan was returned to the emperor, who gave the newly established government permission to govern the country on his behalf. Join me in part ten of this overview of Japanese history to see how Japan fares in this brave new world.